CONTENTS

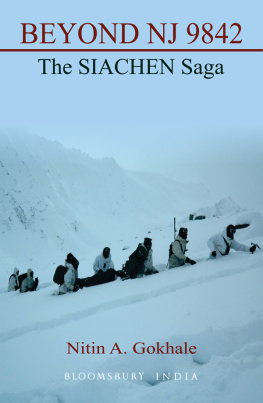

Nearly two decades ago, as a relative newcomer to South Asia, I stumbled into the story of the Siachen war, fought between India and Pakistan for control of the Siachen glacier in the bleak mountains of the Karakoram. The war had begun in 1984 when Indian troops occupied a mountain ridge overlooking the glacier. Pakistan had rushed its own men up into the mountains to drive the Indians out and years later they were still there. Siachen, lying at the point where India, Pakistan, and China meet, had become the worlds highest, coldest battlefield.

I first came across the Siachen war while on a visit to Ladakh, part of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir that has driven conflict between India and Pakistan since independence in 1947. Though I was not able to see Siachen on that first visit it lies on the periphery of Ladakh in a distant military-controlled zone I heard enough to want to know more. This was a war in which more men had been killed by the savage terrain and brutal weather than by gruelling high-altitude battles in ice and snow. Soldiers were posted above 18,000 feet, a height so unsuited to human life that the body has to feed on itself in order to survive. Even so, they had gone out to fight, backed by artillery and mortars. They spent months in isolated posts along a 110 km-long frontline in mountains so high and so bleak that they would deter all but the best mountaineers. Neither India nor Pakistan could win the war the terrain was too hostile to achieve a decisive victory. Nor could they retreat for fear of ceding ground to the other.

In 2003 and 2004 I travelled through India and Pakistan, unravelling the story of the Siachen war. I gathered hours of interviews with men who had been involved in the planning of the war and who had fought in its major battles. I sought out soldiers who could explain to me what it was like to be posted to Siachen. I wrestled with bureaucratic stonewalling to persuade both armies to take me to their side of the battlefield. Thrice, I visited the war zone itself, once driving there over one of the worlds highest roads and then flying to it by helicopter, first with the Indian Army and then with the Pakistan Army. In the course of my research I filled dozens of notebooks with journalistic rigour while writing what I felt and thought in my personal diary.

I published an account of my travels as Heights of Madness: One Womans Journey in Pursuit of a Secret War in 2007. Reading it now, I am struck by the energy and freshness that came from being new to the subject and relatively new to the region I had moved to India as Reuters bureau chief in 2000. Now I have grown more used to South Asia, so that its foibles are more likely to inspire frustration than wonder, though the mountains of the Himalaya and Karakoram still fill me with awe. In 2016 I published a second book, Defeat is an Orphan: How Pakistan Lost the Great South Asian War, which recounts the changing fortunes of India and Pakistan since their nuclear tests in 1998. Since then I have been researching a third book linked to the history of Kashmir.

I decided, however, that the story of the Siachen war deserved a retelling, this time using it as a jumping-off point for looking at the broader nature of conflict all along the periphery of Jammu and Kashmir. Here, in the mountains and high cold deserts between South and Central Asia, three nuclear-armed powers India, Pakistan, and China are embroiled in long-running disputes which have occasionally escalated into all-out war.

The frontier lines separating these three countries are becoming more dangerous and volatile. In the mountains to the east of Siachen, tensions have flared between India and China. The two countries fought a border war in 1962, sparked largely by their disagreement over the delineation of the frontier between Ladakh, Tibet, and Xinjiang in Chinese Central Asia. It ended in a humiliating defeat for India. The border has never been agreed, leading to sporadic stand-offs between the Indian and Chinese armies. In mid-2020, twenty Indian troops and an unknown number of Chinese soldiers died in a skirmish on an arid mountain ridge on the periphery of Ladakh. It was their deadliest clash in more than five decades. In the mountains to the south and west of Siachen, Indian and Pakistani troops face each other across the Line of Control (LoC) which divides the erstwhile princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. It was there that they fought the brief but intense Kargil war in 1999. A ceasefire on the LoC agreed in 2003 has all but broken down, with Indian and Pakistani troops frequently targeting each other with artillery and small arms fire.

To be sure, there are clear distinctions between the various frontiers in the region, among them the Actual Ground Position Line (AGPL) in Siachen, the Line of Control (LoC) between India and Pakistan, and the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between India and China. Seen together, these form a near-unbroken chain around Ladakh, but all three are managed differently, and subject to an array of disparate understandings based on their particular histories. There is, moreover, no neat correspondence between the SinoIndian, the SinoPakistani, and the IndiaPakistan relationships.

In this retelling of the story, then, my aim has not been to produce a definitive account of the three-way contestation between Pakistan, India, and China over the frontiers of Jammu and Kashmir. Rather, I have used my research into the Siachen war to illustrate the confusing and often nebulous nature of both borders and war on this remote high-altitude periphery.

In doing so, I have retained much of my original format, describing the details of how and why the Siachen war was fought, and my own journey through India and Pakistan trying to make sense of it. I have, however, added new segments as I broadened the premise of the book. I have included a discussion of how British imperial borders, once little more than lines on maps, became in the second half of the twentieth century rigid frontiers that had to be defended at all costs. I have also expanded on the history of Jammu and Kashmir. Given the growing tensions between India and China, I have added more details on their 1962 war. Moving forward in time, it is clear to me that the Siachen and Kargil wars are so intimately connected in their geographical proximity that it would be wrong to cover one without the other. I have therefore included two new chapters on the Kargil war.

I have also examined how multiple overlapping conflicts have historically shaped the frontiers of Jammu and Kashmir and continue to do so. In the present day, these include the ideological and strategic contestation between India and Pakistan and their dispute over Kashmir. On the IndiaChina front, Delhi is confronted by a regional rival whose economy has grown to become nearly five times the size of Indias. China frets about warming ties between India and the United States, and about maintaining control over its politically sensitive western periphery in Xinjiang and Tibet, both adjoining Ladakh. These overlapping conflicts are in turn exacerbated by the chains that bind Pakistan, India, and China into an awkward three-way competition. Pakistan distrusts a much larger India, while India fears a more powerful China. An alliance between China and Pakistan, linking them across a land bridge that runs through the Pakistani part of erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir, leaves India and Ladakh in particular hemmed in on two sides.

These overlapping conflicts then meld into the ever-present risk of tactical miscalculations when soldiers are posted in remote and rough terrain, struggling with the high altitude, the penetrating cold, and the rapidly changing weather that make these mountains so unpredictable. Fighting on the frontiers also happens either despite the fact that all three countries involved have nuclear weapons, or because the supposed unthinkability of all-out war means they are more likely to channel their energies into localised conflicts.

Next page