Table of Contents

- Appendix B: Ten Commandments Issued by the

Chief of Army Staff

Dedicated to the people of Jammu and Kashmir, who have borne the brunt of the Pakistan-perpetrated proxy war, and the gallant Indian soldiers who make countless supreme sacrifices to ensure the territorial integrity of India

Contents

Appendix B: Ten Commandments Issued by the

Chief of Army Staff

O ver the last few decades, hundreds of books have been written on the complex situation in Jammu and Kashmir. Authors have approached this topic from many different angles, as a result of which their conclusions have also varied sharply. A number of retired civil servants and high-ranking defence personnel have also expressed their views and given suggestions on how to sort out this highly complicated issue. This book is special because it is written by a retired army chief of staff, General N.C. Vij, who has special insights into Jammu and Kashmir.

After tracing the historical perspective of the state, he covers the invasion, accession and reference to the United Nations in some detail. Thereafter, he deals with the 1965 and 1971 wars with Pakistan and their impact on the state, and then goes on to cover the proxy war by Pakistan, which continues to the present day. After marshalling his facts, General Vij makes several valuable suggestions regarding how to deal effectively with the internal situation in Jammu and Kashmir as well as with Pakistan. He is amongst the few authors who have clearly grasped the tri-regional nature of the state and the fact that the Ladakh and Jammu regions have their own special aspirations, which must be dealt with in any overall settlement. This is in refreshing contrast to the Kashmir-centricity that most authors have adopted.

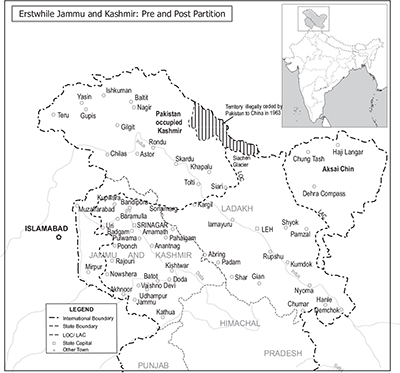

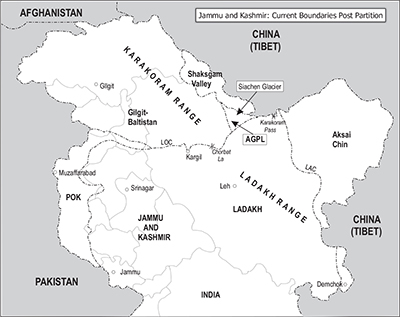

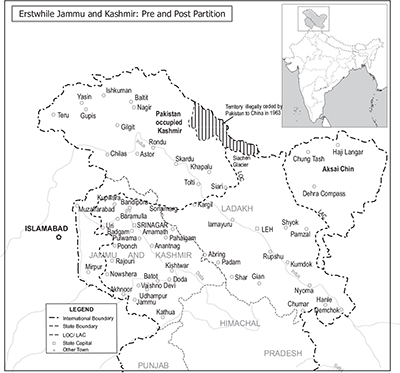

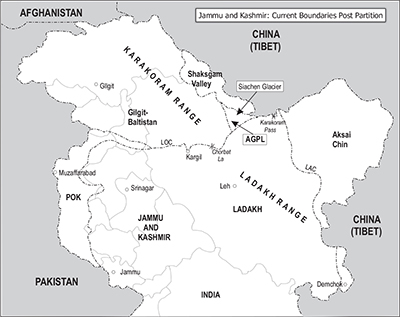

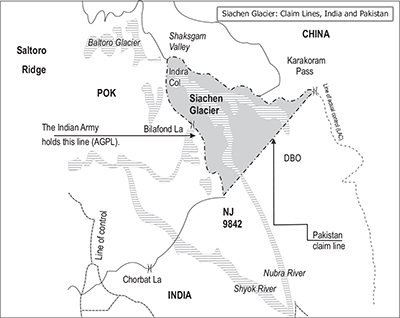

In my view, as I have expressed in Parliament, there are four clear dimensions regarding the state that must be kept in mind. First, whether we like it or not, is the international dimension. About one-third of the population of the original state of Jammu and Kashmir and one-third of its area are under Pakistans control, out of which they have ceded over 5,000 sq. km to China in the Shaksgam Valley to facilitate the Karakoram Highway up to Gwadar Port. In addition, China has captured over 37,000 sq. km of the states territory in Aksai-Chin. Thus, both our nuclear-armed neighbours have muscled their way into the picture. This dimension will therefore have to be tackled at some point in time.

The second dimension involves the relationship of the state with the rest of India. The Instrument of Accession, which my father signed on 26 October 1947 in the wake of the tribal invasion unleashed from Pakistan, is, of course, final and irreversible, and is exactly the same as those signed by other princes. However, there was an important difference between Jammu and Kashmir and the other Indian states. Whereas all the others subsequently signed merger agreements with the Government of India, the relationship of Jammu and Kashmir was based on Articles 370 and 35A of the Constitution, which recognized the states special circumstances.

Subsequent to the accession, a Constituent Assembly was summoned by me on 1 May 1951 to draw up a new Constitution for the state, which came into force when I signed it on 26 January 1957. The Constitution, which clearly reiterated that Jammu and Kashmir would remain an integral part of India, also spelt out its special position. The original understanding was that the relationship would not be changed without the consent of the Constituent Assembly, but when the assembly ceased to exist, this was interpreted to mean the Jammu and Kashmir legislature. Subsequently, a large number of amendments were made by the Government of India that drastically reduced the quantum of autonomy in the state.

The dramatic constitutional developments in August 2019, when both houses of Parliament combined to abolish Articles 370 and 35A and divided the state into two union territories through an unprecedented act of constitutional legerdemain have, of course, drastically altered the situation. The relationship of the two union territories of Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir with the Centre has undergone a sea change. Ladakh has at last achieved union territory status, which it had been demanding for decades. As far as Jammu and Kashmir is concerned, far from enjoying a special position, it is now one notch below other states of the Union. While this step has been widely welcomed in Jammu and Leh, there has expectedly been serious opposition in Kargil and the Valley, in that the last vestiges of their special status have vanished. This has already been challenged in the Supreme Court, and how the whole situation plays out in the future remains to be seen. At the time of writing, it is clear that there is likely to be prolonged unrest in the Valley, while Jammu and Ladakh will consolidate their political situation.

The third aspect, which is often overlooked but which General Vij has clearly appreciated, revolves around the multiregional nature of the state. Jammu and Kashmir was never a single integrated unit; it was brought together by a combination of diplomacy and conquest by my intrepid ancestor Maharaja Gulab Singh in the mid-nineteenth century. The Dogra empire consisted of several far-flung disparate ethnic, linguistic, cultural and geophysical units. In fact, the establishment of the multicultural state of Jammu and Kashmir was one of the major geopolitical events in the subcontinent during the nineteenth century. It extended the boundaries of India all the way up to Tibet and Central Asia, an achievement for which the Dogras have not received due credit. At the time of accession, Gilgit was, in a blatantly illegal act, given to Pakistan by the British commandant of the Gilgit Scouts, Major William Alexander Brown, while the western MuzaffarabadMirpur belt emerged as a separate unit after the ceasefire on 1 January 1949. As a result, only three units are now under Indian administration: Kashmir, Ladakh and Jammu.

Recent developments have fundamentally altered the situation. Ladakh has, at long last, emerged as a union territory, a step that I had publicly advocated as far back as 1965 when I was the governor of Jammu and Kashmir. This fulfils a long-standing demand of the people of Leh, while Kargil will have reservations because culturally they are very different from the Buddhists of Leh-Ladakh. Although Ladakh will not have a legislature, I presume that the Leh and Kargil hill councils will continue to function effectively and in fact be further empowered. Jammu and Kashmir are still linked together in the new union territory. With the proposed delimitation will come the enfranchisement of lakhs of west Pakistan refugees who crossed over to Jammu in 1947 but have not enjoyed permanent resident status and therefore have been deprived of all its benefits through the decades. There are also likely to be, for the first time, reservations for scheduled tribes, which would include the Muslim Gujjars and Bakarwals in the state.