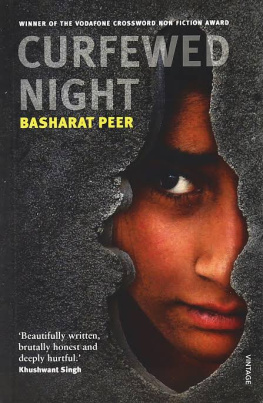

Curfewed Night

One Kashmiri Journalists

Frontline Account of Life, Love,

and War in His Homeland

BASHARAT PEER

Scribner

New York London Toronto Sydney

Scribner

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2010 by Basharat Peer

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

The names and characteristics of some individuals have been changed.

Portions of this memoir first appeared in slightly different forms as essays in N+1 and The Guardian.

First Scribner hardcover edition February 2010

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Book design by Ellen R. Sasahara

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009040416

ISBN 978-1-4391-0910-6

ISBN 978-1-4391-2352-2 (ebook)

In the memory of the boys who couldnt return

home For Baba and for my parents, Hameeda Parveen and G. A. Peer

Contents

People are trapped in history and history is trapped in people.

Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin

The city from where no news can come

is now so visible in its curfewed night

that the worst is precise:

From Zero Bridge

a shadow chased by searchlights is running

away to find its body.

The Country Without a Post Office, Agha Shahid Ali

Part One Memory

1

Fragile Fairyland

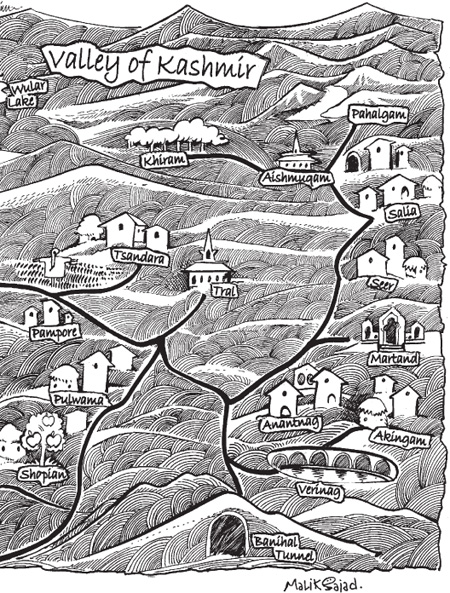

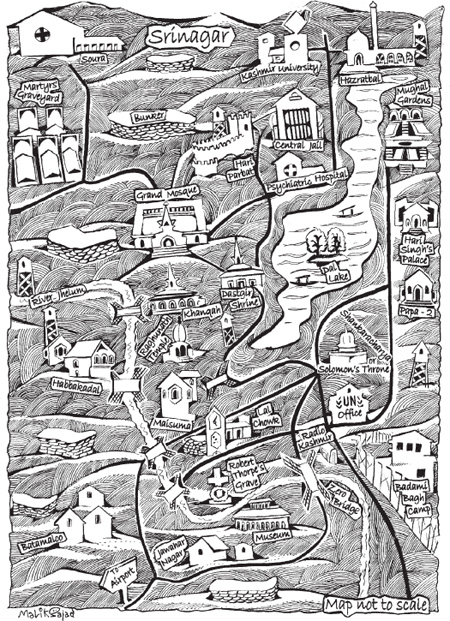

I was born in winter in Kashmir. My village in the southern district of Anantnag sat on the wedge of a mountain range. Paddy fields, green in early summer and golden by autumn, surrounded the cluster of mud-and-brick houses. In winter, snow slid slowly from our roof and fell on our lawns with a thud. My younger brother and I made snowmen using pieces of charcoal for their eyes. And when our mother was busy with some household chore and Grandfather was away, we rushed to the roof, broke icicles off it, mixed them with a concoction of milk and sugar stolen from the kitchen, and ate our homemade ice creams. We would often slide down the slope of the hill overlooking our neighborhood or play cricket on the frozen waters of a pond. We risked being scolded or beaten by Grandfather, the school headmaster. And if he passed by our winter cricket pitch, he expressed his preference of textbooks over cricket through his dreaded shout: You good-for-nothings! At his familiar bark, the cricket players would scatter in all directions and disappear. School headmasters were feared like military and paramilitary men are, not just by their grandchildren but by every single child in the village.

On winter afternoons, Grandfather joined the men of our neighborhood sitting at the storefronts warming themselves with kangris, our mobile fire pots, gossiping or talking about how that years snowfall would affect the mustard crop in the spring. After the muezzin gave the call for afternoon prayers, they left the shop fronts, fed the cattle at home, prayed at the neighborhood mosque, and returned to the storefronts to talk.

Spring was the season of green mountains and meadows, blushing snow and the expanse of yellow mustard flowers in the fields around our village. On Radio Kashmir, they played songs in Kashmiri celebrating the flowers in the meadows and the nightingales on willow branches. My favorite song ended with the refrain: And the nightingale sings to the flowers: Our land is a garden! When we had to harvest a crop, our neighbors and friends would send someone to help; when it was their turn, we would reciprocate. You never needed to make a formal request weeks in advance. Somebody always turned up.

During the farming season, Akhoon, the mullah who refused to believe that Neil Armstrong had landed on the moon, complained about the thinning attendance at our neighborhood mosque. I struggled to hold back my laughter when the villagers eager to get back to farming coughed during the prayers to make him finish faster. He compromised by reading shorter chapters from the Quran. Later in the day he would turn up at the fields to collect a seasonal donationhis fee for leading the prayers at the mosque.

In summer, after the mustard was reaped, we planted rice seedlings. On weekdays before we left for school, my brother and I took samovars of kahwa, the sweet brew of saffron, almonds, and cinnamon, to the laborers working in our fields. On weekends, I would help carry sacks of seedlings from the nurseries; Mother, my aunts, and other neighborhood women bent in rows in the well-watered fields, planted, and sang.

Grandfather kept an eye on a farmer whose holdings bordered our farms. We would see him walking toward the fields, and Grandfather would turn to me: So, whom do you see? I see Mongoose, I would reply. And we would laugh. A short, wiry man with a wrinkled face, Mongoose specialized in things that led to argumentsdiverting water to his fields or scraping the sides of our fields with a shovel to increase his holdings by a few inches.

Mongoose, Grandfather, and all the other villagers worried about the clouds and the rainfall. Untimely rain could spoil the crop. If there were clouds on the northern horizon, they said, there would be rain. And around sunset, if they saw streaks of scarlet in the sky, they said, There has been a murder somewhere. When a man is killed, the sky turns red.

Over more cups of kahwa, the rice stalks were threshed in autumn. Grains were stored in wooden barns, and haystacks rose like mini-mountains in the threshing fields, around which the children played hide-and-seek. The apples in our orchards would be ready to be plucked, graded, packed into boxes of thin willow planks, and sold to a merchant. Village children stole apples; my brother and I would alternate as lookouts after school. Few stole from our orchard; they were too scared of my grandfather. If they steal apples today, tomorrow they will rob a bank. These boys will grow up to be like Janak Singh, Grandfather would say. Many years ago, Janak Singh, a man from a neighboring village, had killed a guard while robbing a bank. He had been arrested and sent to prison for fourteen years. Nobody had killed a man in our area before or since.

Next page

Curfewed Night

Curfewed Night