Table of Contents

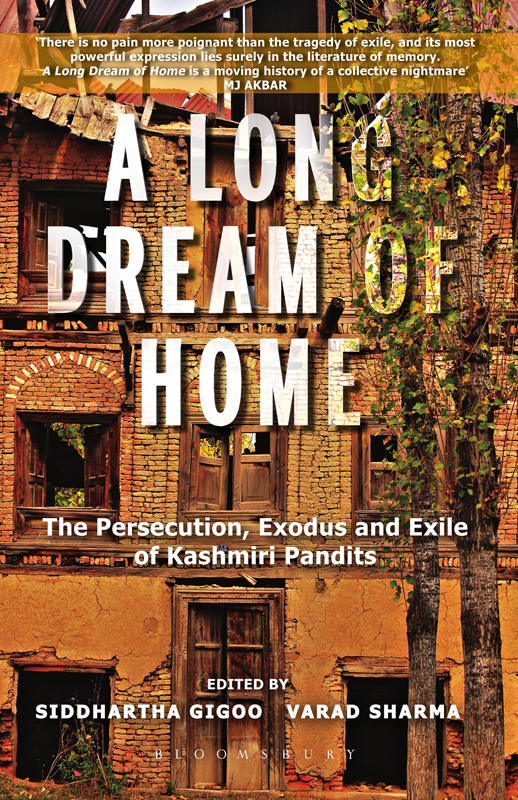

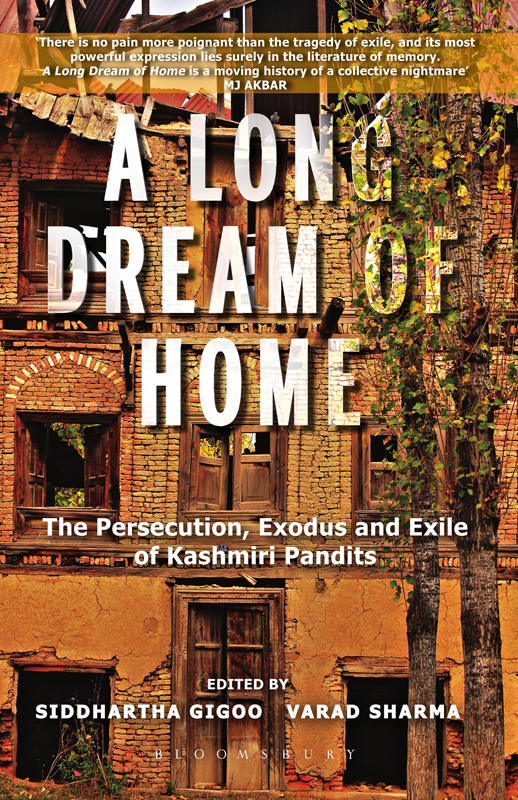

A LONG DREAM OF HOME

A LONG DREAM OF HOME

The persecution, exodus and exile of Kashmiri Pandits

Edited by

Siddhartha Gigoo

Varad Sharma

First published in India 2015

Copyright Siddhartha Gigoo and Varad Sharma 2015

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher would be glad to hear from them.

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Views and opinions expressed in this book dont reflect the views and opinions of the editors and publisher.

E-ISBN 978 93 86250 25 4

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Bloomsbury Publishing India

Vishrut Building, DDA Complex, Building No. 3

Ground Floor, Pocket C 6 & 7, Vasant Kunj

New Delhi 110070

www.bloomsury.com

Created by Manipal Digital Systems.

For Omkar Nath Gigoo, Uma Shori Gigoo, Pushkar Nath Dhar, Pushpa Dhar, Prabhawati Sharma, Prem Nath Sharma, Mohini Pandita and Niranjan Nath Pandita.

In memory of the countless Pandits who perished in exile hoping to return to their homeland, Kashmir.

Imagine living in a strange dark city for twenty years.

CAROL ANN DUFFY, Foreign

When I look ahead I only look back, when I stare at the paper I only see the past.

IMRE KERTESZ, Kaddish for an Unborn Child

And the last remnants memory destroys.

W G SEBALD, The Immigrants

Contents

PART I

Nights of Terror

PART II

Summers of Exile

PART III

Days of Parting

PART IV

Seasons of Longing

Over the centuries, the Hindus of Kashmir (known by the exonym Pandits) have faced persecution by successive Muslim rulers. From 1389 to 1413, Sultan Sikandar Butshikan (destroyer of idols), descendant of Shah Mir, founder of the Shah Miri dynasty of Kashmir, unleashed a reign of terror, imposing jizya (poll tax), ravaging ancient temples and forcibly converting Pandits to Islam. He established Sikandarpora on the ruins of the temples which he razed to the ground. To escape religious conversion, thousands of Pandits fled to Kishtwar and Bhadarwah in Jammu region. Those who didnt leave or refused to be converted to Islam were burned alive at a place near Rainawari in Srinagar. Even today, the place is known as Bhatta Mazar (the graveyard of the Pandits). From 1413 to 1420, Butshikans eldest son, Noor Khan (who assumed the title Sultan Ali Shah) continued his fathers policy of intolerance towards Pandits. Noor Khans brother, Zain-ul-Abidin (Budshah), succeeded to the throne in 1420. Pandit Shri Bhat, a physician who cured the king of a disease, influenced him to turn sympathetic towards Pandits. Zain-ul-Abidin abolished the jizya and allowed the Pandits to rebuild their temples. Pandits flourished under his rule which lasted fifty years. Thereafter, the Chak and the Mughal dynasties took over. The repression continued during their rules especially during Aurangzebs reign from 1658 to 1707.

The period from 1753 to 1819 was another dark period in the history of Kashmir. During this time, Afghans under Ahmad Shah Durrani ruled Kashmir and persecuted Pandits by reintroducing jizya and forcing them to embrace Islam. The Afghan rulers made oppression of Pandits their political policy. In 1819, Mirza Pandit Dhar and Pandit Birbal Dhar, who were revenue collectors under the zealot Afghan governor Azim Khan, secretly persuaded Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Lahore to annex Kashmir to bring an end to the Afghan rule. Maharaja Ranjit Singhs forces under Diwan Chand, Gulab Singh of Jammu and Hari Singh Nalwa defeated the last Afghan governor Jabbar Khan. From 1819 to 1947, Kashmir was under the Sikh and Dogra regimes.

In October 1947, during Maharaja Hari Singhs rule, tribal militias from Pakistans North-West Frontier Province, supported by the Pakistani army, invaded Kashmir, killing hundreds of Hindus. To save Kashmir from Pakistani aggression and an imminent occupation, Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession with India on 26 October 1947, paving the way for the Indian Army to enter Kashmir to defeat the invaders.

With the eruption of Pakistan-sponsored armed insurgency in Kashmir in 1989, Pandits became soft targets for the militant outfits who wanted to wipe out the Indian element and liberate Kashmir from India. Many Pandits were on the hit lists of several militant groups. The night of 19 January 1990 was one of terror for Pandits. Kashmir resonated with anti-India and anti-Pandit slogans. Mass protests and violent clashes between militants/protestors and security forces crippled the state administration. The law and order situation collapsed.

In April 1990, Hizb-ul Mujahideen, a militant outfit gave the Pandits an ultimatum to leave Kashmir in 36 hours or face dire consequences. Suspicion, betrayal and mistrust divided the Muslims and the Pandits. Both the communities stood divided on religious and ideological lines. Militants kidnapped and killed several ordinary and prominent Kashmiri Pandits. This created so much panic and fear among the Pandit families that they started leaving their homes in Kashmir. Some, who didnt want to leave, sent their children away and lingered on in their homes for some time, hoping that the turmoil would end. Some of the Pandits managed to carry a few belongings while most left empty-handed in terror, unable to pack even their necessary household possessions. The security forces including the police were unable to provide protection to the minority community. The authorities in the state and the centre made no effort to prevent the atrocities committed against the Pandits. Targeted kidnappings and killings, rapes and massacres of Pandits who lingered on became a routine affair. The massacre of Pandits by militants in Sangrampora, Budgam in March 1997, Gool in June 1997, Wandhama near Ganderbal in January 1998 and Nadimarg, Pulwama in March 2003, made it clear that Pandits were not safe in their own land.

By the end of 1990, about half a million Pandits had left their homes in Kashmir. The displaced people sought refuge in Jammu and adjoining districts. Thousands found shelter in temples, sheds, barns, canvas tents and schools. Many others took rooms on rent. The role played by the people of Jammu was commendable at those critical times. The displaced, jobless Pandits, many of them agriculturists, lived on the meagre dole given to them by the government. They suffered in migrant camps and private rented accommodations in Jammu and nearby districts. The camp-dwellers lived in deplorable conditions in canvas tents and ramshackle one-room tenements that lacked even basic civic amenities. In these cramped spaces there was neither privacy nor security and safety. It was a life of degradation, deprivation and indignity. Year after year, the exiles struggled, nurturing hope and battling a deep sense of alienation and desolation. Thousands perished due to diseases, mental sicknesses, heat strokes, sunstrokes, hostile climatic conditions and accidents.

During the nineties, Kashmir passed through its darkest years of conflict and political upheaval in contemporary history. The popular uprising of the Muslims of Kashmir against the Indian state was met with force by the security forces. Hartals, civil curfews, mass protests, stone-pelting, bomb blasts, encounters, strikes, violent clashes between the militants and the security forces, army crackdowns and detentions, became a way of life in Kashmir. Army and paramilitary forces launched full-scale operations to curb militancy. Thousands of Kashmiri Muslimsyoung and oldlost their lives. Kashmir became one of the most militarised zones in the world and a very dangerous place to live and visit. The cycle of protests and violence continues even now. There is no political solution in sight to restore peace, stability and normalcy in Kashmir.