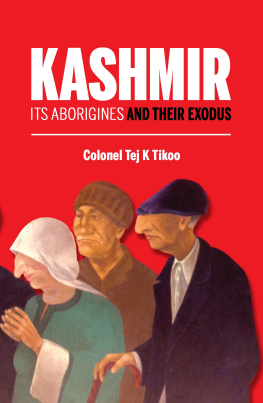

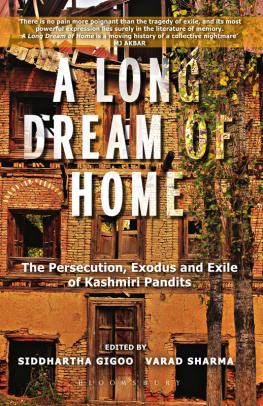

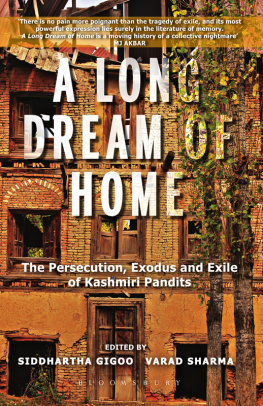

Around 3.5 lakh Pandits migrated from Kashmir to Jammu in 1990 because of the political turmoil created by militancy and terrorism. They were made to stay in schools and temples. Others lived in rooms rented out to them by the people of Jammu. Most felt that it was a question of a month or so before they would go back to the land of their birth, Kashmir. But the conditions in Kashmir deteriorated. The killings of the Kashmiris continued unabated. There was total chaos and confusion bordering on anarchy. Hope turned into despair and helplessness.

Jammu and Delhi were alien places for Pandits. They could not adjust to the new environment and circumstances. As time went by, the Pandits shifted from the schools and temples to tents in camps erected for them. There they experienced loss of privacy and physical intimacy and negative epiphany. Human relationships were shattered. Pandits became nomadic and un-homed subjects in a no-mans-land of waiting, anxiety and suffering. They were traumatized and stuck in limbo, not knowing what to do next. Their loneliness came out in genuine complaints, lamentations and nerve-racking dreams. They suffered the ignominy of fall and anomie.

This was ethnic cleansing or migration of the worst type in independent India. The effect of this migration devastated the mental make-up of Pandits. Migration created health and psychological problems of great magnitude for them. Not knowing how to cope with the heat, many Pandits died due to heatstrokes. Alzheimers, amnesia and dementia affected many. A sense of insecurity, fear, suspicion, mistrust and alienation, apprehensions about the loss of identity, new diseases, adverse effect of climatic conditions, and feuds and acute tensions invaded their lives.

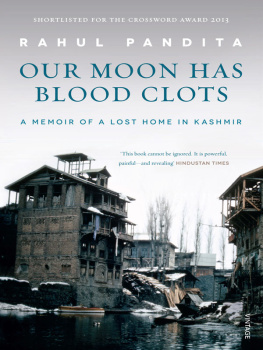

In spite of this displacement, the Pandit writers wrote novels, poems, short stories, essays, memoirs and satirical writings in English, Hindi, Urdu and Kashmiri in which they gave vent to their grief, anger and their longing to return to Kashmir. For them writing became a vehicle for nostalgia and for expressing their unfathomable dark anguish. Like others they had seen the end of humanism, they had seen heaven turned into hell.

In November 1990 Rattan Lal Shant wrote an essay in Hindi, Visthapan Aur Kashmiri Visthapan Sahitya (Literature of Kashmiris in Exile), in which he defined the exile of Pandits and analysed their writings produced till then. Kashmiri Pandit exiles founded literary associations and journals in Jammu, Delhi and some other cities. In the literary meetings the writers exchanged ideas on literature, recited poems and read out short stories and research papers. Their writings in various genres appeared in the periodicals. Many books on culture, language, history, script, art, ritual, identity, religion, politics and sociology were published. The Devanagari script for Kashmiri language evolved. Even many non-Kashmiris wrote on the harmful effects of migration on the miniscule minority of Pandits. In this way a new genre, Literature in Exile, took shape in India for the first time.

Muslims living in Kashmir wanted the Pandits to come back. They felt that Kashmir without Kashmiri Pandits is incomplete. At the time of the mass migration of Pandits, Muslims were helpless, mute spectators. The fear of the gun had silenced all. Militants wanted the Pandits out of the valley. Many Pandits and Muslims had been killed. The situation was out of control.

The administrative machinery was a total failure. Everything had collapsed. The processions and religious slogans created terror in the peace-loving Pandits about whom Iqbal has written:

Those sprightly sons of Brahmans

Have faces that shame the red tulip

Taking their rise from our charming soil

They shine as the stars on Kashmir horizon.

(Translation by Mohammad Amin.)

Still, one wonders why the Muslims allowed this exodus of Pandits to happen. Their silence and defenceless apathy towards a very tragic human situation gave rise to suspicion, mistrust and fear in Pandits.

Thousands of Pandits lived in tents from 1990 to 1995. Then they were shifted to one-room tenements (without bathrooms and kitchens) constructed at various places in Jammu and Udhampur. They lived in them till 2011. The government then constructed one-room flats (with bathrooms and kitchens) for them at different places in the Jammu province. Pandits have been living in them since 2011. These flats have only been allotted to the Pandits; they dont own them.

There are neither tents nor one-room tenements now. The largest camp (known as Mini Township for Kashmiri Migrants) with one-room flats is at Jagti, 17 kilometres from Jammu city. Three thousand five hundred families live there. Khatris, Rajputs, Sikhs, Kashmiri Punjabis and even some Kashmiri Muslims who migrated from Kashmir, live in the camp. Other camps with one-room flats are at Nagrota, Buta Nagar, Muthi and Purkhoo in the Jammu province. When the mass migration ended only 4,000 Pandits remained in the valley. At present 18,000 Pandits live in Kashmir. One thousand four hundred youths went to Kashmir in 2007-2008 under a scheme launched by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and joined the government services.

When the Pandit exiles lost all hope of return to the valley, they sold their properties and lands in Kashmir and started constructing their own houses at different places in Jammu and other cities of the country. Many Pandits bought flats and apartments in Delhi, Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh, Bangalore, Pune and at other places. The joint family system died its own death and was replaced by the nuclear family system. The Pandit youths working in the private sector are scattered throughout India and the world. The old feel alienated and ignored; many among them are living alone in houses and apartments. Some of the elderly people are living in old-age homes. In the summers, to avoid the heat, many Pandits go to Kashmir, stay there in hotels, rented houses, temples and ashrams, visit tourist places, and interact with their old Muslim friends and neighbours. Now Pandits are visitors to their motherland, Kashmir. They visit those tourist places where they had never gone when they lived in Kashmir. They come back with a sense of satisfaction for having visited their land of birth.