Introduction

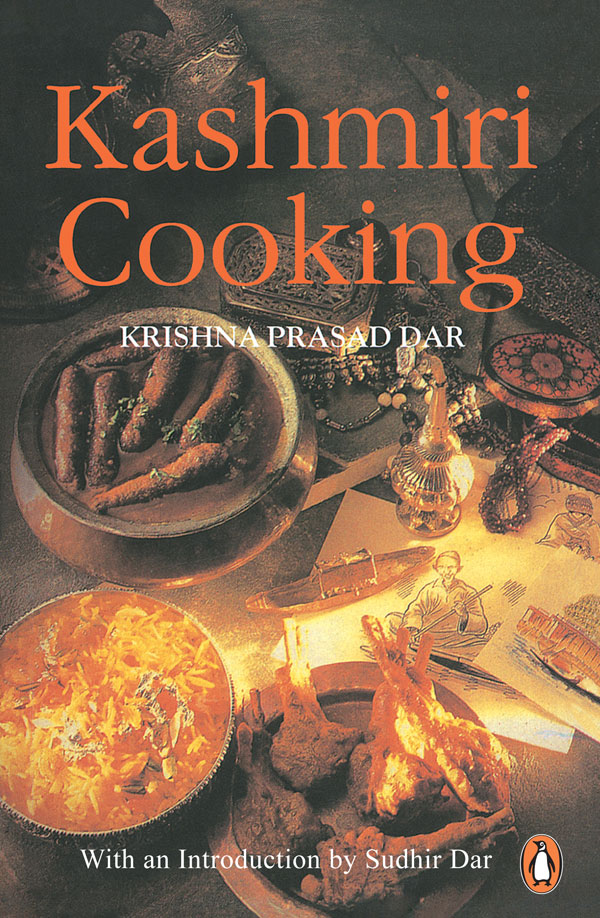

My father was a gourmet of gourmets, having acquired the traditional art of Kashmiri Pandit cooking from his mother and the professional cooks employed in their home during his years of adolescence and youth. But for several decades the recipes remained closetted in his mind until he was persuaded by family and friends to reveal the magic of the age-old culinary skills of one of the worlds finest cuisines.

Those were the days.

In the early years of this century, every other Kashmiri Pandit home in the plains had a professional Kashmiri cook in residence, whose mastery of his art was demonstrated twice a day, at lunch and dinner. Cooks came for as little as Rs 10 per month, with food, shelter and clothing. Pure ghee, then, was less than a rupee a seer, mustard oilfour seers for a rupee, so one can imagine the extravagance. Each meal was an event, each dish a gourmets delight, every day a royal feast.

Over the years, the ladies of the household acquired specialized training from these culinary masters and in due course, became as proficient as their gurus. In another generation, living costs multiplied and less and less homes could bear the heavy expenses of a princely diet. The era of the super cooks was over. Many drifted into government service, others set up mini-restaurants, some became hotel cooks, several returned to Kashmir. Their sons seldom took to the profession. Today, they can be counted on the fingers of one hand. However, they are still available, still as masterly as ever, still the backbone of many a Kashmiri Pandit wedding, Kashmiri Pandit cuisine evolved in the Valley several centuries ago and in course of time absorbed some of the delectable elements of the Mughal art of cooking and, thus enriched, acquired a distinct personality of its own. Hence you will find in this book certain non-vegetarian dishes of Mughal origin which have been given a Kashmiri touch.

Kashmiri cooking developed through the ages as two great schools of culinary craftsmanshipKashmiri Pandit and Muslim. The basic difference between the two was that the Hindus used hing and curd and the Muslims onions and garlic

Now a few points of interest about the two cuisines.

Though Brahmins, Kashmiri Pandits have generally been great meat eaters. They prefer goat, and preferably, young goat. Meat is usually cut into somewhat large pieces and is mostly chosen from the legs, neck, breast, ribs and shoulder. Curd plays an important part in our cuisine. No meat delicacy, except certain kababs, is cooked without curd. Even in vegetarian dishes, it is often added. Ideally, Kashmiri Pandit food needs heat on two sides (top and bottom) and the best results are obtained from a charcoal fire. However, in these days of electric stoves, gas and pressure cooking, less and less homes use charcoal (an oven serves as a good substitute).

Originally, onions and garlic were never used in Kashmiri Pandit cooking. But as many of us have acquired a taste for them, they have been included in certain recipes as optionals. Though the basic principles of cooking are largely similar in almost all our homes, certain Pandit families have adopted minor changes in both ingredients and methods. The methods given in this book are the ones our family has followed over decades. The book may not be the last word on Kashmiri cooking, but I can assure readers that if the instructions are carefully followed, the results should be satisfying. My father had cooked each dish in this book time and time again, some literally hundreds of times. He was really a master craftsman. Our home in Allahabad was so full of delicious aromas from the kitchen that I couldnt help being hungry all the time I must confess at this point, however, that my own knowledge of Kashmiri food is confined more or less to the fine art of eating When youve tried your hand with dishes like Kabargah, Kofta, Dum Alu, Methi Chaman, Firni etc., youll see why.

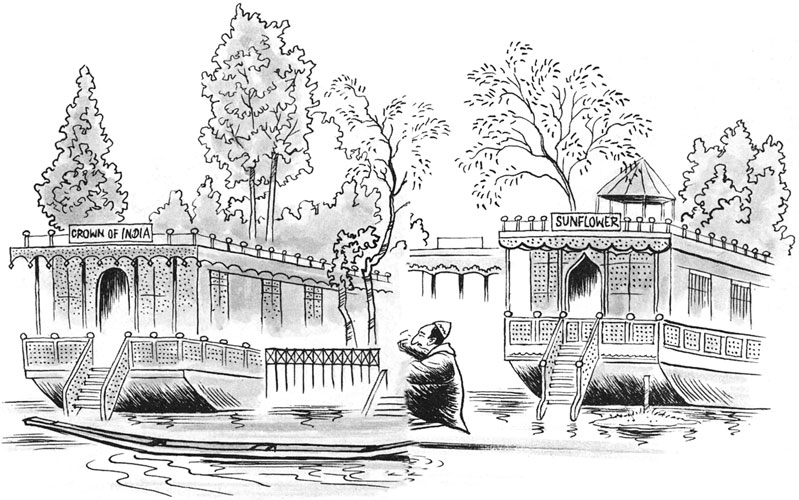

Kashmiri Muslim cuisine is another gold mine of gourmet cooking to explore, another treasure trove of exotica to savour. Except for some hotels and a few restaurants in India which promote or cater to regional tastes, this highly prized art too has remained largely confined to Kashmiri homes in and out of the Valley. However, professional cooks in Kashmir still continue to thrive, though more and more are beginning to face an uncertain future as the days of lavish hospitality are on the decline and current conditions have reduced the occasions for feasting to traditional festivals, banquets and marriages.

Known as wazas, these cooks are descendants of the master chefs who migrated from Samarkand and parts of Central Asia at the beginning of the fifteenth century and formed a vital part of the entourage that came to Kashmir during the reign of Timur (or Tamarlane). There were 1700 masters of one kind or another. Amongst them were great craftsmen, wood carvers, carpenters, architects, carpet weavers, shawl makers, calligraphists, masters of embroidery and other skilled hands. In the turbulent history of Kashmir, it is considered as an age of renaissance.