Foreword

The troubles in Jammu and Kashmir have produced a small libraryof books in the three decades since their onset. Propagandists,pamphleteers and scholars alike have probed almost every aspect ofthe Kashmir question. But like many other enduring conflicts, thediscourse on Jammu and Kashmir is one of contested claims, wherethere is no one truth but several competing narratives.

In many ways, the history of Kashmir is like the Kurosawa epicfilm Rashomon. There are many honest narratives, but no singleauthentic version. Every bit of Kashmir is deeply challenged: theland, the people, the politics andabove allthe events that haveshaped its destiny. Every single significant happening in the KashmirValley over the last seventy-odd years has countless versions: eachaccount has its own devoted followingblindly attached to andbelieving that their understanding alone is the final truth.

Added to this are the myopic policies of the governments inDelhi and Islamabad that will not declassify even seventy-year-oldrecords on Kashmir lest they compromise national security. In aworld, then, where scholars are treated like infiltrators and statepropaganda machineries seek to construct a grand discourse thatwill suit their tactical endswhile genuine intellectual subversivesrisk being eliminated or totally marginalizedcan real history-writing have a chance?

Not surprisingly, much of what has been produced onKashmir, especially in the last three decades, is drivel. I have apersonal collection of about 1500 books and pamphlets publishedduring these years, and, save a handful, all of them would be most useful on a cold winter Kashmir evening, generating warmth in a bonfire. The exceptions are those that seek to reconstruct historiesbefore 1947, those that look for sources outside South Asia or relyprimarily on subaltern (and oral) sources. Indeed, the two mostoutstanding recent contributions to Kashmirs historiography beganas doctoral dissertations in American universities and imaginativelyused a combination of British imperial records in London and theunpublished manuscripts and private papers of Kashmiris.

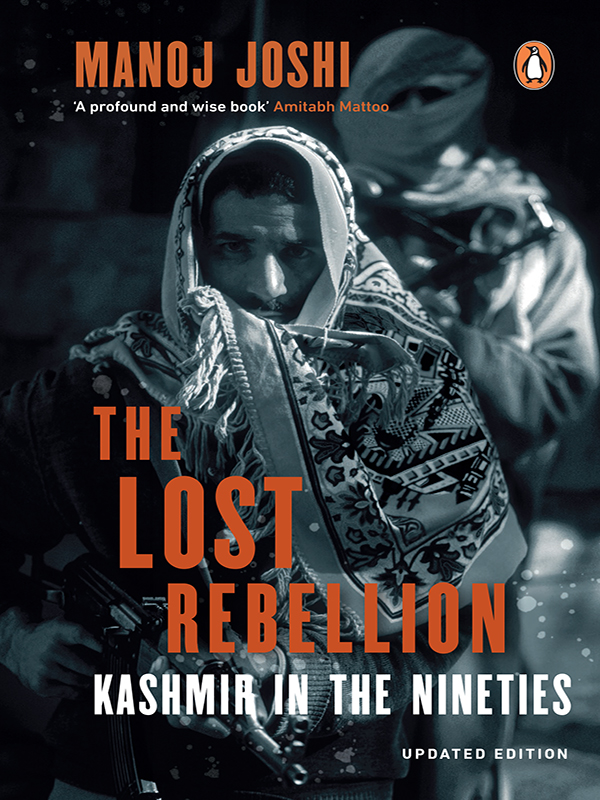

Can, then, the story of the precise manner in which theinsurgency was organized by the militants and the strategies usedby the Indian security forces in the 1990s be narrated in any greatdepth or with a fair degree of objectivity? Manoj Joshis magisterialbook proves that with understanding, determination and a mix ofsources it is possible to craft such a narrative.

Indeed, Joshis is the first detailed account of the full scale ofthe militant operation and the Indian states response to what wasprobably the strongest challenge faced by it since 1947. Fluentlywritten, in a style that combines the reader-friendly approach of ajournalist with the understanding of a military historian, The LostRebellion, despite the exhaustive details, makes for fascinating andgripping reading. It was originally published in 1999 and the newedition brings us up to date with the latest developments.

Although there are rarely any attributions, the book has quiteobviously relied heavily on the confessions of captured militantsand their debriefing by Indian security and intelligence agencies.

The anecdotal asides in the book are particularly engaging.Consider this one about Robin Raphel, the former Americanassistant secretary for South Asia, who quickly became the btenoire of the Indian establishment for her stand on Kashmir:

Her calls on India to reduce human-rights abuses andclean up your act in Kashmir or get your act togetherhit a raw nerve.

The mandarins of South and North Block did not wantto hear this message, not from an American and that tooa woman. IB officials tapping her line added spice to thisby reporting to their masters the not-very-complimentaryterms in which they were referred to by Raphel.

Raphel has not changed very much. A known friend and lobbyistof Pakistan, these days she is helping Washington negotiate withthe Taliban. And while Joshi does identify and narrate instancesof civil-rights violations by Indian security forces, he seems toultimately suggest that they were inevitable in what was a singularlydirty war.

However, The Lost Rebellion is principally about the uncivilwar in Kashmir rather than the deeper roots of that violence. AndJoshi does draw a distinction between the professionalism of theIndian Army and the insensitive approach of agencies like theBorder Security Force.

Moreover, behind the military-history garb and the no-nonsenseguns and ammo approach, The Lost Rebellion is ultimately areflection of the Indian state: hard on the surface and liberal atthe core. This is reflected particularly in many of the passages inthe concluding chapter, including this one: Pakistans neuroticobsession with Kashmir has been matched by New Delhis singularinability to forge a policy that is more effective in anticipatingdevelopments, sensitive to human rights and consequently moreattuned to winning back the hearts and minds of the KashmiriMuslims of the Valley.

Ultimately, then, the original book seemed to suggest that theIndian state had shown its hard face to the Kashmiri people in the1990s, and that it was now time to start the process of healing toensure that the scars of the lost rebellion are well and truly erased.Sadly, that never happened.

The first edition of this book was completed at the end of1998 and published in early 1999. In the troubled recent historyof the state, 1999, as Joshi pointed out, was a watershed of sorts.Having more or less crushed the rebellion and having conductedthe state assembly elections in 1996, the Indian state hoped that itcould, over time, restore normalcy in the state. What was requiredwas a sustained reaching out to the people of the state. That neverhappened.

Prime Ministers Manmohan Singh and Atal Bihari Vajpayeedid recognize the need to address the alienation of the peopleof Jammu and Kashmir, but for a variety of reasons their mostimaginative initiatives were short-lived. Today, however, in the garb of national interest, ad hocism, bureaucratic inertia and plain ineptitude are the hallmarks of New Delhis approach to a once-again sinking Jammu and Kashmir.

This new edition is a profound and wise book, and Joshi goesbeyond the tactical concerns of the Indian state. It is a book thatmust be read by every concerned Indian citizen.

Professor Amitabh Mattoo

Former adviser to the chief minister of

Jammu and Kashmir

List of Abbreviations

AFP: Agence France-Presse

AFSPA: Armed Forces Special Powers Act

ANE: Anti-national element

APHC All Party Hurriyat or Liberation Conference

BBC: British Broadcasting Corporation

BJP: Bharatiya Janata Party

BPRD: Bureau Police Research and Development

BSF: Border Security Force

BSP: Bahujan Samaj Party

CBI: Central Bureau of Investigation