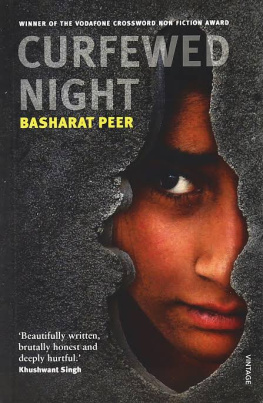

Basharat Peer - Curfewed Night

Here you can read online Basharat Peer - Curfewed Night full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: RANDOM HOUSE INDIA, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Curfewed Night

- Author:

- Publisher:RANDOM HOUSE INDIA

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Curfewed Night: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Curfewed Night" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Curfewed Night — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Curfewed Night" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CURFEWED NIGHT

Basharat Peer

RANDOM HOUSE INDIA

Published by Random House India in 2008 13579108642

Copyright Basharat Peer 2008 Random House Publishers India Private Limited

MindMill Corporate Tower, Ilnd Floor, Plot No 24A, Sector 16A,Noida 201301

Random House Group Limited, Vauxhall Bridge Road United Kingdom.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Private Limited

In the memory of the boys who couldn't come home For my parents, Hameeda Parveen and Ghulam Ahmad Peer, and for baba, Mohamad Ahsan Sheikh

People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them. James Baldwin, Stranger in the Village

Chapter One

I was born in winter in Kashmir. My village in the southern district of Anantnag sat on the wedge of a mountain range. Paddy fields, green in early summer and golden by autumn, surrounded the cluster of mud and brick houses. In winter, snow slid slowly from our roof and fell on our lawns with a thud. My younger brother Wajahat and I made snowmen using pieces of charcoal for their eyes. And when our mother was busy with some household chore and grandfather was away, we rushed to the roof, broke icicles off it, mixed them with a concoction of milk and sugar stolen from the kitchen, and ate our homemade ice creams. We would often slide down the slope of the hill overlooking our neighbourhood or play cricket on the frozen waters of a pond near the hill. We risked being scolded or beaten by grandfather, the school headmaster, on the way back home. And if he passed by our winter cricket pitch he expressed his preference of textbooks over cricket through his dreaded shout, 'You good for nothings!' At his familiar bark the cricket players would scatter in all directions and disappear. School headmasters were feared like military and paramilitary men are, not just by their grandchildren but by every single child in the village. On winter afternoons, grandfather joined the men of our neighbourhood sitting on the storefronts warming themselves with kangris, our mobile firepots, gossiping or talking about how that year's snowfall would affect the mustard crop in the spring. After the muezzin gave the call for afternoon prayers, they left the shopfronts, fed the cattle at home, prayed at the neighbourhood mosque, and returned to the storefronts to talk.

Spring was the season of green mountains and meadows, blushing snow and an expanse of yellow mustard flowers in the fields around our village. On Radio Kashmir, they played songs in Kashmiri celebrating the flowers in the meadows and the nightingales on willow branches. My favourite song ended with the refrain: 'And the nightingale sings to the flowers: Our land is a garden!' When we had to harvest a crop, our neighbours and friends would send someone to help; when it was their turn we would reciprocate. You never needed to make a formal request weeks in advance. Somebody always turned up. During the farming season, Akhoon, the mullah, who refused to believe that Neil Armstrong had landed on the moon, complained about the thinning attendance at our neighbourhood mosque. I struggled to hold back my laughter when the villagers, anxious to get back to farming, coughed during the prayers to make him finish faster. He compromised by reading shorter chapters from the Quran and then turning up at the fields to collect a seasonal donationhis fee for leading the prayers at the mosque. In summer, after the mustard was reaped, we planted rice seedlings. On weekdays, before we left for school, my brother and I took samovars of kahwa, the sweet brew of saffron, almonds, and cinnamon, to the labourers working in our fields. On weekends, I would help grandfather and other men carry sacks of seedlings from the nurseries; my mother, aunts, and other neighbourhood women bent in rows in the well-watered fields, planted and sang. Grandfather would always keep an eye on a farmer whose holdings bordered our farms. We would see him walking towards the fields and grandfather would turn to me, 'So whom do you see?' 'I see the Mongoose,' I would reply. And we would laugh. A short, wiry man with a much wrinkled face, Mongoose specialised in diverting water to his fields, or grazing the sides of our terraced fields to push the wedge further and increase his landholdings by a few 2

inchesthings that would lead to arguments. But Mongoose, grandfather, and all other villagers worried about the clouds and the rainfall. Untimely rain could spoil the crop. If there were clouds on the northern horizon, they said, there would be rain. And around sunset if they saw streaks of scarlet in the sky, they said, 'There has been a murder somewhere. When a man is killed, the sky turns red.' Over more cups of kahwa, the grain stalks were threshed in autumn. Grains were stored in wooden barns and haystacks rose like mini-mountains in the threshing fields, around which the children played hide and seek. And the apples in our orchards would be ready to be plucked, graded, packed into boxes of thin willow planks, and sold to an apple merchant. Village children stole apples; my brother and I would alternate as lookouts after school. Few stole from our orchard; they were too scared of my grandfather. 'If they steal apples today, tomorrow they will rob a bank. These boys will grow up to be like Janak Singh,' grandfather would say. Many years ago, Janak Singh, a man from a neighbouring village had killed a guard while robbing a bank. He was arrested and sent to prison for fourteen years. Nobody had killed a man in our area for decades. On the way back from school I would often stare from the bus window at Janak Singh's thatch-roofed house as if seeing it once again would reveal some secret. My housea three- floor rectangle of red bricks and varnished wood covered by a cone of tin sheetsfaced the same road, a mile ahead of Janak Singh's. I would stand on the steps and watch the tourist buses passing by. The multi-coloured buses carried visitors from distant cities like Bombay, Calcutta, and Delhi; and also many angrezthe word for the British, and our only word for westerners. The angrez were interesting; some had very long hair and some shaved their heads. They rode big motorbikes and at times were half-naked. I had asked a neighbour who worked in a hotel, 'Why do the angrez travel and we do not?' 'Because they are angrez and we are not,' he said. But I worked it out. They had to travel to see Kashmir; we lived there and did not need to travel. We waved at them; they waved back. Father had bought me an American comic book dictionary, which taught words using stories of Superman, Batman, Robin, and Flash, the scientist who controlled electricity. I would often read it by the jaundiced light of our kerosene lantern and think if Flash lived in Kashmir, we could have asked him to fix our errant power supply. I preferred reading the comics to the sums my grandfather wanted me to master. They added new stories to the collection of Persian and Kashmiri legends I heard from my grandmother and our servant Akramlegends such as the tale of the commoner Farhaad's unrequited love for Shireen, the queen of Persia, who agreed to a rendezvous if he would dig a stream of milk from a mountain to her palace. My family ate dinner together in our kitchen-cum-drawing room, sitting around a long yellow sheet laid out on the floor, verses of Urdu and Farsi poetry extolling the beauty of hospitality painted in black along its borders. Dinner often began with grandfather leaning against a cushion in the centre of the room, then turning to my mother: 'Hama, looks like your mother will starve us today.' Grandmother would stop puffing her hookah and say, 'I was thinking of evening prayers. But anyway, let me feed you first.' And she would amble towards her wooden seat near the earthen hearth above which our tin-plated copper plates and bowls sat on various shelves. Mother would put aside her knitting kit or the papers of her students and briskly move to arrange the plates and bowls near grandmother's throne. Wajahat would half-heartedly bring out the long yellow sheet and I would fill a jar with water and get the bowl for washing hands. 'Call the girls/ mother would say and I would go upstairs to announce to my aunts that dinner was ready. Two of my younger auntsTasleema and Rubeenastill lived with us; the others were married but visited often with their kids and husbands. Tasleema, the geek, always poured over thick chemistry and zoology texts or prepared some speech for her college debating society, practising her hand gestures in front of a mirror. Rubeena didn't care much about textbooks but had great interest in women's magazines, detective fiction, and Bollywood songs that always played at a low volume on her transistor, strategically placed by her side, to be switched off quickly if she heard someone climbing the stairs. We would form a circle with grandfather as its nucleus and eat. Almost every time we cooked meat or chicken, he would cut a portion of his share and place it on my plate, and tell Tasleema to bring a glass of milk for Akram, who would be visibly tired after a long day of work at the orchards or the fields. We would gather in the morning around a samovar of burgundy coloured salty milk tea and then grandfather and mother left to teach and my aunts, my brother and I left for our colleges and schools. My school, a crumbling wooden building in the neighbouring small town of Mattan, was named Lyceum after Plato's academy. Saturdays meant quizzes, debates and essay competitions. Once I got the first prizethree carbon pencils and two notebooks wrapped in pink paperfor writing about the hazards of a nuclear war. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were just names to memorise for a quiz, as were the strange names of those bombsLittle Boy and Fat Man. I concerned myself with learning to ride a bicycle, with playing cricket for my school team, grabbing my share of fireen, a sweet pudding of almonds, raisins, milk, and sooji topped by poppy seeds, served during a break in the nightlong prayers at our mosque before Eid, or trying to stretch the pre-dawn eating time limit during Ramadan.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Curfewed Night»

Look at similar books to Curfewed Night. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Curfewed Night and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.