For all those who put fifty pence in the jukebox of the Richmond Springs, Brison, between 1988 and 1992.

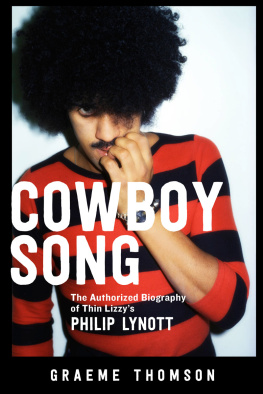

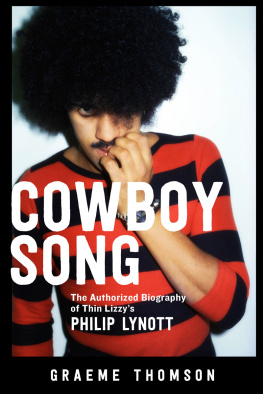

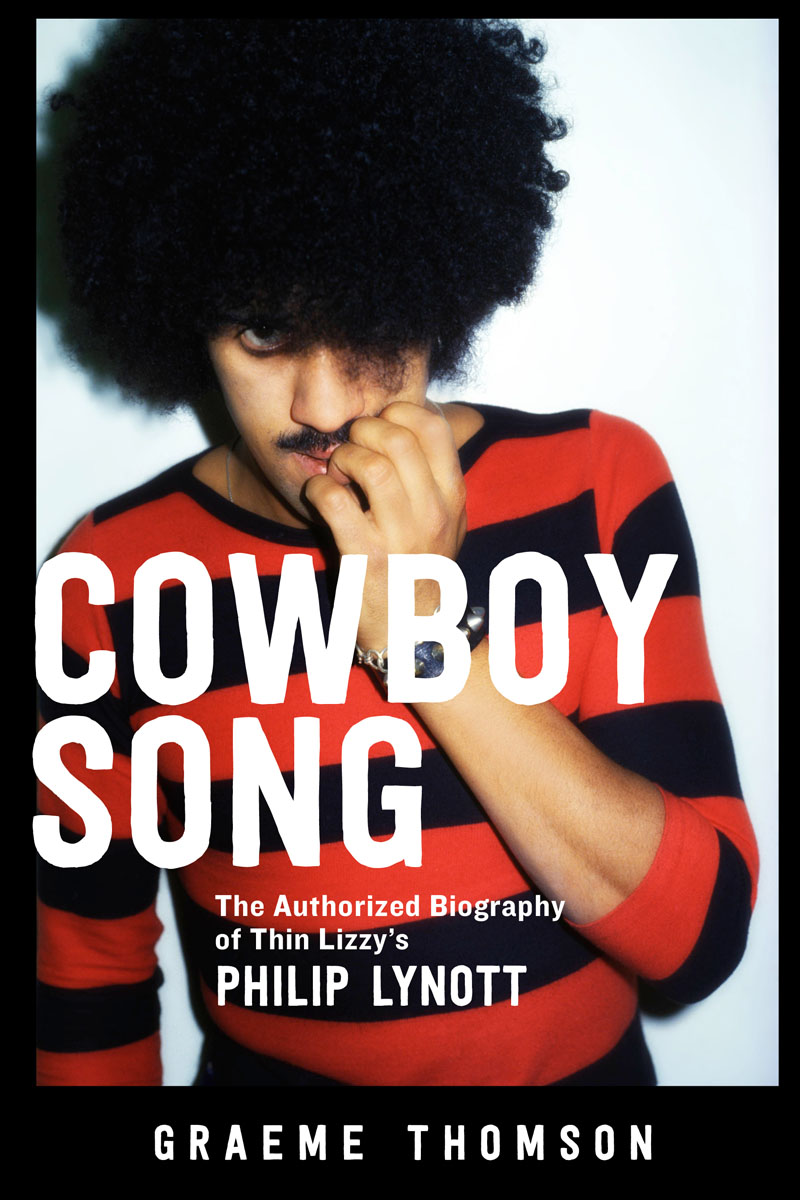

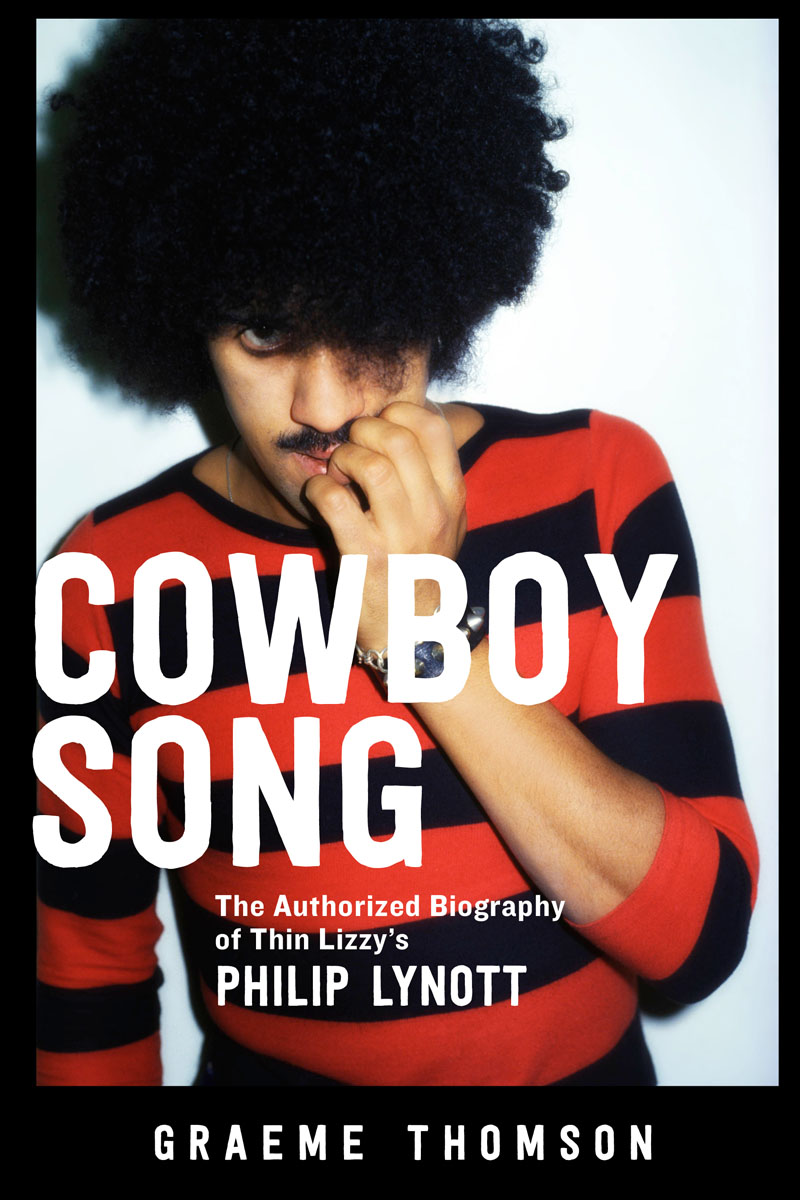

Cowboy Song: The Authorized Biography of Thin Lizzys Philip Lynott published in the United States of America in 2017 by Chicago Review Press Incorporated.

First published as Cowboy Song: The Authorised Biography of Philip Lynott in the United Kingdom by Constable.

Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-919-8

Copyright 2016 by Graeme Thomson

Cover design: Debbie Berne Design

Cover image: Phil Lynott of Thin Lizzy backstage, circa 1979. Photo by Denis ORegan/Getty Images

Interior design: SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, Essex

All lyrics written by Philip Lynott reproduced with permission of the Lynott estate.

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

The Irish are the niggers of Europe, lads, Jimmy Rabbitte tells his band of white would-be soul singers in Roddy Doyles The Commitments. An Dubliners are the niggers of Ireland Say it loud, Im black an Im proud.

If Dubliners were the blacks of Ireland, then being an actual black Dub was a veritable double whammy of otherness. In 1957 on his first day at the Christian Brothers School in Crumlin, the eight-year-old Philip Lynott stood in the playground while his classmates lined up to touch his hair.

Automatically, he was like a peacock, says Paul Scully, a fellow Southside Dubliner. He was exotic. He stood out. I remember Philip coming to my mothers house and she whispered to me, Does he drink tea?

The long, lean, coffee-skinned boy with no father and an absent mother became a celebrity simply by existing. By the 1970s he would be the Republic of Irelands first ever bona fide rock star.

By 1986, he was gone.

For Philip Lynott, fame was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Its outline was always there; he simply needed to fill in the detail. It did not take long. He was a local band leader at the age of fourteen, the singer in Irelands best rock group at eighteen, and had formed Thin Lizzy by the time he was twenty. When the full force of his talent finally caught up with his looks, drive and charisma in his mid-twenties, Lynott seemed unstoppable.

Thin Lizzys gold-standard records Jailbreak, Johnny the Fox, Bad Reputation, Live and Dangerous are both powerful and strangely beautiful. They are often described as a hard-rock band, even heavy metal, which undersells the soulful mix of machismo, melody, poetry, mischief, rhythm and attack Thin Lizzy conveyed at their peak. Amid the swagger, there was always a lightness of touch; beyond the smoke-bombs and sirens lay a determination for things to be better and smarter than they needed to be.

On stage, Thin Lizzy became masters of the live ritual. For five years in the second half of the 1970s, Lynott was the quintessential rock-and-roll frontman. He controlled and coaxed and electrified crowds to the extent that he became synonymous with the image on the front of their classic concert album, Live and Dangerous, a Dionysian study in leather trousers, studded wristband, clenched fist and gypsy earring.

He was so ridiculously good at being a rock star, he inhabited the role with such obvious relish, its easy to overlook all the other attributes Lynott had going for him. He could speak freely in the language of music, says drummer Mark Nauseef. Not many rock guys can do that. He had so much going on. People didnt see a lot of it.

Had he never written a single song, his voice alone would have marked him out. Its not really a rock voice at all. The wood-smoke timbre, the high-wire sense of timing and off-beat phrasing position Lynott closer to folk and jazz. He was a crooner seduced by high voltage and heavy wattage; the mournful grain was always an essential part of his appeal.

If his voice brought out the soul of Thin Lizzy, his words delivered the substance. Lynotts early lyrics have a poetic flourish. They are a young mans words, anxious to impress, but often very beautiful. The tenor of peak-period Thin Lizzy, on the other hand, was all cinematic street-smarts, every adjective and noun armed with a flick knife and a sharply turned-up collar. Few lyricists have proved so adept at placing the listener right in the centre of the action.

He wrote melodies that have endured. Although numerous hard rock and heavy metal bands from Megadeth to Metallica, Foo Fighters to Def Leppard cite Thin Lizzy as a key influence, perhaps more telling is the diversity of artists who have performed Lynotts songs, among them Pulp, Sade, the Hold Steady and the Corrs.

He was a fine bass player. He was a phenomenal band leader. He was a wired-up perfectionist who affected the lassitude of Johnny Cool. He knocked around with poets and snooker players, fishermen and gangsters, Johnny Thunders and Georgie Best. He read comics and Camus and had a deceptively sprawling hinterland.

This is a story about Lynotts life in Thin Lizzy, but it is also a story about all the other things he was and could have been, inside and outside of music.

It is a story with an unhappy ending. Lynott did not always behave well, nor did he always make the smartest choices. In later life his addictions and insecurities made him a difficult man to be around, and ultimately they overpowered him.

But there is also much to celebrate. As the first full-blooded rock star to break out of his homeland, Lynott signalled the possibility for a new kind of Ireland: confident, swaggering, unbowed. His image, aspects of which can seem faintly ridiculous in retrospect, was potency writ large. As the late Irish writer Bill Graham said of Lynott. He was the most masculinely sexual of any Irish star before or since, at a time when we were struggling to escape the prison of our repressions. The jailbreak Lynott sang about was real. The Boomtown Rats and U2 tunnelled out after him. In time it became an exodus.

That it took a black, illegitimate, English-born, Irish-Guyanese man to roll back the frontier is rather wonderful, even if Lynott regarded himself as an Irishman first, last and always. He entirely viewed himself as Irish, says fellow Dubliner Bob Geldof, returning to Jimmy Rabbittes theme. The old Black Irish thing youre an outsider anyway. He was totally Irish, in every sense. He couldnt be more Irish.

And yet no matter how Irish he felt or sounded, Lynott appeared to be the precise opposite. This distance between the seeming and the being is part of his story. It was an existence filled with tensions and contradictions, playing out over thirty-six years. They resulted in some wonderful times and music, and some soul-scouring lows. He lived many different lives, says Noel Bridgeman, a friend since their days together in Skid Row. There were different levels. His personality was paradoxical.

The Irish poet and publisher Peter Fallon told me: Philip rose and he fell, and somehow that rise and fall was simultaneous. At times in this tale Lynott looks like someone who threw it all away. At other times he looks like a man who spun gold from a fistful of thin air. Of course, he was both, and more, and all at once.

PART ONE

Dublin

There are several recurring archetypes in the songs of Philip Lynott, each one a form of self-portrait. The streetwise hustler (lets call him Johnny; Lynott usually did) of The Boys Are Back in Town and Johnny the Fox Meets Jimmy the Weed; the flinty Celtic warrior of Eire and Risn Dubh (Black Rose): A Rock Legend, chiselled from Irish mythos; the amped-up main man of The Rocker and Black Boys on the Corner; the sad-eyed lothario of Romeo and the Lonely Girl and Randolphs Tango.

Next page