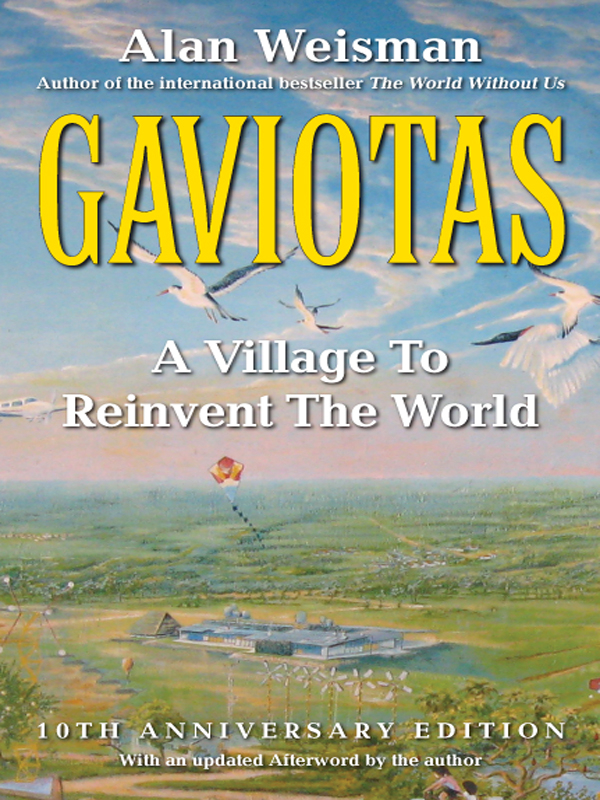

gaviotas

gaviotas

A VILLAGE

TO REINVENT

THE WORLD

Alan Weisman

CHELSEA GREEN PUBLISHING COMPANY WHITE

RIVER JUNCTION, VERMONT

Portions of this book have appeared earlier, in different form, in the Los Angeles Times Magazine, the New York Times Magazine, and on National Public Radio.

Lines quoted from El Saucelito, copyright 1995 by Jorge Eliecer Landaeta, are by permission of the composer.

Permission by the authors for use of material from the following is gratefully acknowledged: Bernal, Gonzalo L. La Sonrisa de Los Bosques. Obra inedita, 1995.

Zethelius, Magnus, and Michael J. Balick. "Modern Medicine and Shamanistic Ritual: A Case of Positive Synergistic Response in the Treatment of a Snakebite." Journal ofEthnopharmacology (Lausanne) 5 (1982): 181-85.

Copyright 1998 by Alan Weisman.

New Afterword copyright 2008 by Alan Weisman.

Illustrations copyright 1998 by Michael Middleton.

Maps copyright 1998 by Don Marietta, Hedberg Maps.

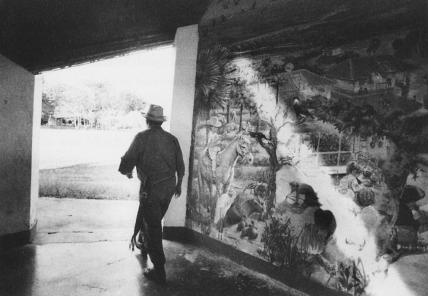

Photographs copyright 1998 by Antonin Kratochvil.

Calligraphy by Bonnie Spiegel.

Text design by Ann Aspell.

Printed in the United States of America on recycled paper.

First printing, this edition, July 2008

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15

The Library of Congress cataloged the original edition with the following Cataloging-in-Publication data:

Weisman, Alan.

Gaviotas : a village to reinvent the world / Alan Weisman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60358-092-2

1. ColumbiaEnvironmental conditions. 2. Human

ecologyColumbia.

3. ColumbiaDescription and travel. I. Title.

GE160.C7W45 1998

338.9861dc21

97-48395

Our Commitment to Green Publishing

Chelsea Green sees publishing as a tool for cultural change and ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book manufacturing practices with our editorial mission and to reduce the impact of our business enterprise on the environment. We print our books and catalogs on chlorine-free recycled paper, using soy-based inks whenever possible. Chelsea Green in a member of the Green Press Initiative (www.greenpressinitiative.org), a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the world's endangered forests and conserve natural resources. Gaviotas was printed on 60# Joy White, a 30-percent postconsumer-waste recycled paper supplied by Thomson-Shore.

Chelsea Green Publishing Company

PO Box 428

White River Junction, Vermont 05001

(802) 295-6300

www.chelseagreen.com

for Beckie

Content

IN 1994, A TEAM OF INDEPENDENT JOURNALISTS WAS FUNDED BY THE Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Ford Foundation, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to produce a series for National Public Radio, which would document humanity's search for solutions to the greatest environmental and social problems threatening the world. One member of that team, Alan Weisman, took his quest to an unlikely spot: war-torn, drug-ravaged Colombia. Twenty-five years earlier, he'd been told, a group of Colombian visionaries had decided that if they could fashion self-sustaining peace and prosperity in the most difficult place on earth, it could be done anywhere. Then they had set out to try.

For sixteen hours, Weisman traveled by jeep past roadblocks manned by army, paramilitary, and guerrilla forces to reach what those visionaries had forged in the harshest setting they could find: the extraordinary community called Gaviotas.

Support for this book was generously provided by:

The Burr Oak Fund of the Tides Foundation

Kristie Graham of the Amazon Foundation

The Macon and Regina Cowles Foundation

The Westport Fund

Homelands Research Group

YEARS BEFORE BELISARIO BETANCUR BECAME PRESIDENT OF COLOMBIA and proceeded to startle his fractured nation by risking a fledgling peace with Marxist insurgents who, at that time, ruled more territory than the government; before he filled the halls of state with works and recitals by Colombia's greatest painters, musicians, and poets, and invited the public in to see and hear; before he had the wizards from Gaviotas outfit his presidential mansion with their artful devices that coaxed the sun's bountiful energy through Bogot's dour skieslong before all that, he heard a story that he never forgot.

It was the kind of thing, he explained thirty-five years later to Paolo Lugari, the founder of Gaviotas, that jerked everything else into perspective. "It still does. Listen."

"I will, Presidente. And then I have one for you."

This was March, 1996: They were in Betancur's northeast Bogota apartment, sipping chamomile tea. Outside, a cold rain pummeled the 9,000-foot skirts of the Andes. The roundfaced, silver-haired former president, now 73, sat in his leather chair, wrapped in a thick blue sweater and red wool scarf. Lugari, bearded and burly, evidently oblivious to the chill, wore his usual lightweight tropical suit. In his large hands, the china cup and saucer looked frail as eggshells.

"The year," Betancur began, "was 1962. I was a senator then."

A senator: Back then, the very notion had seemed miraculous. Belisario Betancur was one of twenty-three children born to nearly illiterate peasants. When he was eight, he'd found an illustrated volume of ancient history on his village school's bookshelves. Intrigued by the quaint pictures, he learned to read it. Soon he was scouring encyclopedias for more about the Peloponnesian wars, about Carthage, about the Roman emperor Hadrian, about anything Greek or Latin.

At his teachers' urging, his stunned parents eventually sent him to a seminary in Medelln, where he spent the next five years conversing solely in those classical languageseven on weekends, when Spanish was permitted, because he was routinely being punished for some breach of cloister decorum. His masters ultimately concluded that, however brilliant, he was too impetuous for the priesthood; the rector who expelled him arranged for his placement in a university. There he studied law and architecture, but ended up a journalist.

It was not an auspicious time. In 1948, Colombia had fallen into a horrific civil war; over the following decade, an epoch known today simply as La Violencia, hundreds of thousands died. There was little of comfort to report, but during those years Betancur discovered something of which most of his compatriots seemed barely aware: To the east of the Andes, which bisect Colombia like a great diagonal sash, lay half the country, virtually uninhabited save for scattered bands of nomadic Indians.

Next page