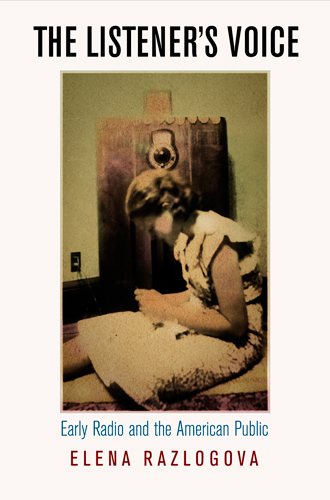

Copyright 2011 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available

from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-4320-8

Preface

_______

The Moral Economy of American Broadcasting

When Gang Busters came on the air Nanny Roy was packing her granddaughters suitcase. It was nine oclock in the evening in September of 1942. It did not take her long to realize that the story concerned her son. Twelve years previously, she sold dresses at a ready-to-wear shop in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, her husband ran electric trains at a foundry, and her son, Virgil Harris, processed corn at a starch factory. Then Harris became an armed robber, was caught and jailed, escaped, diedgunned down by state policeand joined the ranks of Depression-era bandits immortalized by true crime magazines, movies, and radio. Nanny Roys granddaughter was leaving for college. Protective of her privacy, Roy promptly mailed a complaint to the sponsor, Earl Sloan and Company. The company forwarded her letter to program supervisor, Leonard Bass, whose response can be surmised from Roys second letter. I cannot except your regrets, she declared:

I understand perfectly if I were a mother with high financial standing this would never of happed. you cant deny the crime of all sorts the worst of all the robbery that happens every day thru the rich and mighty from the poor. why not expose them. put your investigator at work on the people who are stealing thru their capacity officially. This sort of crime is worse to me than if a person point a gun at me and demand all I have. Yet it goes on. An 18 year old boy steals a sack of feed an inner tube or a tire and he gets sentenced to 20 years in an institution. let the big feller rob in his undermining way theres no publicity he goes on lectures to society and is met by the broadcasters with a hand-shake.

The true crime show had failed Nanny Roy in a variety of ways. Its researchers had pried into her family history. Its writers had omitted aspects of her sons life that drove him to rob banks. Its sponsors and producers had brushed off her point that workers turned to banditry to survive the Great Depressiona recent memory even as the country began to recover during the war. A modern reader might wonder why she bothered to correspond with broadcasters at all, given how well she understood and articulated the complicity of the commercial broadcasting industry in the inequities of American capitalism. Yet she did write, twice, and received a response. Nanny Roys letter conveys both her sense of social justice and her expectations of reciprocity from the radio industry.

Many Americans shared her sentiments. Between 1920 and 1950, during the golden age of radio, they extended communal values to the increasingly complex national economy and politics. Populist movements revolted against the rise of the impersonal bureaucratic nation state and modern industrial society. The union rank and file believed in moral capitalism, a social order where industrial employers had a responsibility to provide a fair share for workers. Large corporations advertised themselves as friendly neighborhood stores to appease restive consumers. And the expanding federal government had to meet rising expectations of fairness from the loyal citizenry. This moral economy governed the development of radio as an industry and a mass medium. The industry operated on tacit assumptions that held broadcasters responsible to their audiences. Americans looked to radio not only to reflect but to resolve some of the tensions they felt about the nature of big institutions, the location of social power, and the future of both market and political democracy. This book describes how their expectations shaped the medium.

Today, the idea that listeners sense of justice shaped broadcasters production practices appears to defy common sense. Once the main ground for scholarly battles over media effects and national culture, in the era of television radio became the province of memorabilia and tape collectors. Ronald Reagans deregulation policies made it relevant again, inspiring influential studies of how advertising and corporate monopoly stifled programming and technical innovation. Participatory amateur radio in the early 1920s gave place to one-way local commercial, educational, and non-profit broadcasting. Following the Radio Act of 1927 and especially the Communication Act of 1934, national networks dominated broadcasting and consolidated American national culture. After the ratings services appeared in the early 1930s, broadcasters rarely confronted real listeners, only demographics classified According to this birds eye view of the industry, listeners had little impact on its everyday organization but bore the brunt of the consequent corporate media system.

To those who take a closer look, however, radios past seems less decided. Local stations in the 1920s, it turns out, forged symbiotic relationships with their farmer, immigrant, and middle-class neighbors. The networks did not blanket the entire country until the late 1930s. Regional chains and local stations continued to operate alongside the national system. The Federal Communications Commission used antitrust law to break apart the National Broadcasting Company in 1943. Commercials that hailed shopping as a form of citizenship inspired consumer boycotts. Network programs created a sense of intimacy rather than an impersonal national culture. Listeners imagined personal connections with radio characters, and expected scriptwriters, actors, and sponsors to heed their advice. These new accounts amend the tale of network and commercial dominance. They begin to explain why so many Americansover 80 percent by 1940owned radios and listened on average for four hours daily, and why in a pinch families would rather give up their furniture, linen, or icebox than their radio set. George Washington Hill, the president of the American Tobacco Company and one of the first radio sponsors, defined radio as 10 percent entertainment and 90 percent advertising. His often-cited quip becomes more programmatic than descriptive once one looks, as this book does, beyond business plans and political debates to the everyday practices and expectations at work in the making of broadcasting.

The Listeners Voice argues that audiences were critical components in the making of radio, the establishment of its genres and social operations. During the Jazz Age and the Great Depression, with no scientific structure yet available to analyze and predict audience response, radio producers created devices and programs relying on individual listeners phone calls, telegrams, and letters. In their responses, Americans demanded access to radio production, aiming also to reframe the terms on which modern institutions, the radio industry included, structured their lives. In this period, listener response inspired changes in radio technology, genres, and institutions. Writers and stars used their relationship with listeners to gain some creative autonomy from network and agency executives. By wartime, however, the broadcasting industry relied mainly on scientific management of audiences. Ratings and surveys of specialized markets shaped production choices. Radio genres had standardized and producers no longer invited listeners to participate in the creative process, allowing them only to express taste preferences. Networks consolidated their power over programming decisions, edging out input from audiences, agencies, writers, and stars. It also became harder for radio personalities to convince listeners that their individual testimonies mattered. But scientific marketing never triumphed completelyas television producers embraced ratings, audiences gained more control over local radio. By the time postwar prosperity arrived, centralization and scientific methods gave way to local reciprocal forms of radio production.