Ashleigh Wilson is the arts editor of The Australian. He won a Walkley Award in 2006 for his series on unethical behaviour in the Aboriginal art industry, which led to a Senate inquiry. His book Brett Whiteley: Art, Life and the Other Thing was published by Text Publishing in 2016.

Little Books on Big Ideas

Blanche dAlpuget On Lust & Longing

Fleur Anderson On Sleep

Gay Bilson On Digestion

Julian Burnside On Privilege

Paul Daley On Patriotism

Robert Dessaix On Humbug

Juliana Engberg En Route

Sarah Ferguson On Mother

Nikki Gemmell On Quiet

Stan Grant On Identity

Germaine Greer On Rape

Germaine Greer On Rage

Sarah Hanson-Young En Garde

Jonathan Holmes On Aunty

Susan Johnson On Beauty

Malcolm Knox On Obsession

Barrie Kosky On Ecstasy

David Malouf On Experience

Paula Matthewson On Merit

Katharine Murphy On Disruption

Leigh Sales On Doubt

Mark Scott On Us

Natasha Stott Despoja On Violence

Tim Soutphommasane On Hate

David Speers On Mutiny

Anne Summers On Luck

Don Watson On Indignation

Tony Wheeler On Travel

Elisabeth Wynhausen On Resilience

Ashleigh

Wilson

On

Artists

For Zoe and Raphael

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2019

Text Ashleigh Wilson, 2019

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Text design by Alice Graphics

Cover design by Nada Backovic Design

Author photograph by Mclean Stephenson

Typeset by TypeSkill

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522875256 (paperback)

9780522875263 (ebook)

It has invariably happened that the works which they have made have been, in some degree, the proofs of the character of the workmen; for who is there who, when he looks upon statues or pictures, does not at once form an idea of the statuary or painter himself? And who, when he beholds a garment, or a ship, or a house, does not in a moment conceive a notion of the weaver, or shipbuilder, or architect, who has made them?

Philo Judaeus, the Alexandrian philosopher, roughly two thousand years ago

Lets begin with the filmmaker whose obsession with his female lead ended her career. They were worlds apart: he was a formidable figure, already one of the greats, while this was her first film. He had noticed her in a television advertisement. Now he was making her a star.

On their first movie together, his fixation was obvious to the crew. He stared at her constantly. He showered her with gifts. He had her followed when she was away from the set. He told her what to wear and who to see socially. On their second movie he built her a trailer with a private entrance to his office, which is why she learned to invite friends over to avoid encountering him alone. When he finally made a sexual advance that she couldnt ignore, she turned him down. His retaliation was immediate: he froze her out during the remainder of filming and then killed her career.

Half a century before Harvey Weinstein changed everything, Alfred Hitchcock was in California, making life hell for Tippi Hedren. Their first film together was The Birds; the second was Marnie. While shooting The Birds in 1962, Hitchcock subjected Hedren to a sustained period of emotional and physical torture during the climactic scene, when her character comes under attack in a room full of seagulls, crows and ravens. Those were real birds, and Hedren collapsed after several days of filming. She later described this as the worst week of her life.

The next film, Marnie (1964), had a strange plot. Businessman Mark Rutland (Sean Connery) becomes besotted with a thief, Marnie Edgar, after she steals from his company. He convinces her to marry him, rapes her on their honeymoon and then discovers the childhood trauma that made her fear intimacy. Hitchcock had originally wanted Grace Kelly to play Marnie, but when he settled on Hedren his obsession went up another notch. He even asked the make-up department to create a life mask of her face for his own use. You dont need to know what happened behind the scenes to find some of the dialogue unsettling:

Marnie: Just let me go, Mark, please. Mark, you dont know me. Oh, listen to me, Mark, I am not like other people. I know what I am.

Mark: I doubt that you do. In any event well just have to deal with whatever it is that you are. Whatever you are, I love you. Its horrible, I know, but I do love you.

Marnie: You dont love me. Im just something you caught. You think Im some kind of animal you trapped.

Mark: Thats right, you are. And Ive caught something really wild this time, havent I? I trapped you and caught you and by God Im going to keep you.

It was during the filming of Marnie that Hitchcock tried to become intimate with Hedren. After she refused, he started calling her the girl around the set and lost interest in the film. He then refused to release her from her contract and told other filmmakers she was unavailable for future roles.

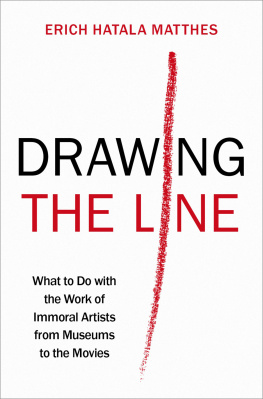

He was a sexual predator, but he was also Alfred Hitchcock, and he had the power to ruin careers.

But that was then.

***

In late 2017 the fall of Harvey Weinstein prompted profound conversations about power and misogyny in the modern world. Weinstein, one of the most influential producers in Hollywood, was accused of sexually assaulting dozens of women over his long career. His behaviour had been an open secret, but that silence was over. A new movement was born, one that came to be known by a hashtag of inclusion, amplifying a cause that had first been named a decade earlier: #MeToo.

After Weinstein other public figures have also fallen from grace, and more will follow. But already there is one development pushing back against hundreds of years of tradition: the excuse of the creative genius. No longer is the artist allowed to live apart from the rest of society. No longer can the artist be excused from the standards of conduct that apply to us all. This excuse has been circulating for centuries: to be creative was to be prone to eccentricity, melancholy, madness, addiction, neurosis, reclusiveness, egotism, penuryor any number of flaws said to contribute to the cost of making art. Great art may well demand a certain character from its maker, but the tolerance of the past has been cast aside.

Next page