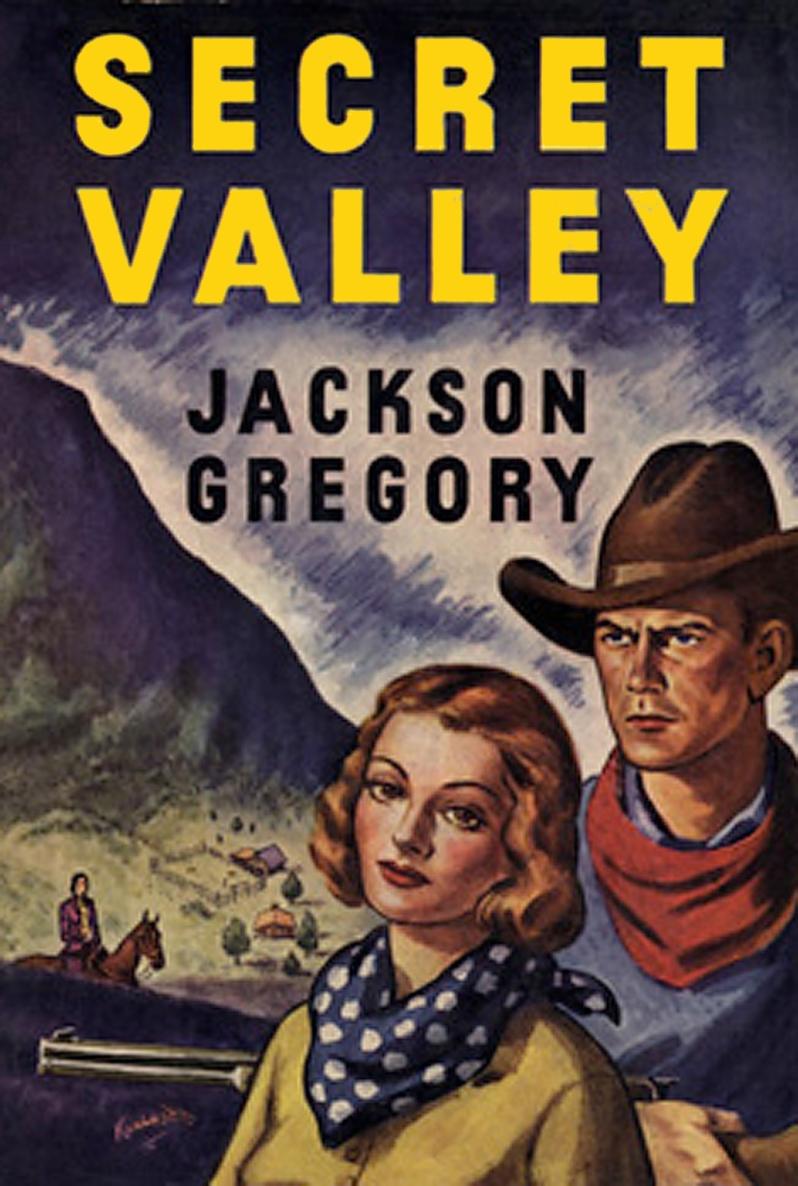

CHAPTER I

IN THOSE DAYS, if you got to Fiddlers Gulch, most folks said you got to the end of the world. It was far, very far out in the Western Wilderness.

Then, if you went on any farther, you got to Three Fools Pass. And thus you came inescapably to the old monstrosity of a house squatting there, high up on the mountain ridge, Black Jack Devlins place. The Mountain House, they called it.

And if you got thereWell, some said it was well worth the long and hazardous journey, and others of paler blood were sorry they had ever left some snug berth in the land where the sun came up. Here the sun went down, a glorious, warm, red sun.

Black Jack Devlins place hunkered on a benchland just above the pass; from its wide puncheon porches under shake roofs you could look down on one hand into the shadowy depths of Secret Valley. You could look down, on the other hand, into the mysterious gloom of Lost Valley. For the pass was high up, commanding a hogs back ridge which separated the two dark, dusky, fertile and somehow both forbidding and lovely valleys.

Black Jack Devlin himself was a gambler of the old school.

He had a daughter who was the apple of his eye. Her name had been Rose Devlin. Later she decided on Rosalie. At run-away sixteen she named herself Rose-alba. She had read a fairy tale with a Rose-alba in it; that meant White Rose. She loved white roses; they were rare in her life; she had seen only one that a man had brought from Santa FA She wanted, in certain moods, to be a white rose herself.

Not only was she a gamblers daughter; she was a gambler.

During that year not less than seven hundred men had poured through the pass, many going on lingeringly, not to come back; many more passing back and forth, back and forth, between the mines in the north and the town of Liberty down in the lower country. Out of the seven hundred, perhaps six hundred and ninety-odd wanted her.

She was young, and so she dramatized herself. She dressed like something very exotic she had seen pictured in a magazine which had straggled up here, months old, from Santa FA It came not long after the white rose. And she was intrinsically lovely.

Also, like most gamblers, like her father Black Jack Devlin, she cheated at cards. And she got away with it.

There, to start with, we have something of Black Jack Devlin, and a drop more of Rose-alba.

The wide porch of the Mountain House skirted three sides of the rambling old log-and-stone building. From the eastern porch you looked down into Secret Valley; that was where the Haverils dwelt and rioted and squandered all they ever possessed. From the southern end, high above the rocky backbone of the ridge, you got glimpses of the lower ends of both deep-cleft valleys. From the west you looked down into Lost Valley; that was where Tom Storm held forth.

Then there was a third valley, and its owner held it to be not only the finest of all but quite the most lovely spot on earth, a perfect Vale of Alombroso, and accordingly named it the Valley of Paradise. Only, being an old and sentimental Spanish gentleman, his name for it was El Paraiso, which means Paradise, so everyone called it Paradise Valley. The conformation of the mountains here was peculiar; ancient glaciers had worked their wills eons earlier and had gone the way of all flesh and ice; they had left behind them deep gorges like Norwegian fiords, and tall sheer cliffs; there was the ridge high up on which stood the old Mountain House, with that spine of rock creating a high barrier between Secret Valley and Lost Valley. Then, toward the south, the ridge was split asunder, and between its halves lay the head of Paradise Valley.

The old Spanish family of Valdez y Verdugo, having moved up from Santa Fe a hundred years earlier, had held it all the while, a tolerant and bountiful and merciful God alone knowing how.

And down in Paradise Valley, too, there was a girl.

She was the niece of old Seor Francisco de Valdez y Verdugo. She was like a flower; like a southern flowerlike a magnolia. Also she was pretty much like a young queen, as haughty and soft-handed and useless, and used to issuing decrees.

So, then, there were these people whose life-lines, all without their suspecting it, were of a sudden to be entangled:

Black Jack Devlin.

His reckless, picturesque, card-playing daughter, Rose-alba.

Tom Storm down in Lost Valley.

Don Francisco, lording it over Paradise Valleyand at times biting his aristocratic nails and lifting hungry eyes toward the lofty Mountain House.

The Spanish-American girl, like a queen, for whom the Valley of Paradise was such a proper setting, the Seorita Carmencita.

And there was a Haverilone of the Secret Valley Haverilsthough for years he had been somewhere down in South America. But tired of adventuring, remembering his boyhood home in the mountains in the Southwest, for which he grew homesick after fifteen years of life on the far, open trails, he had at last harkened to the slap-slap of waves out on the Pacific, heading north againthinking of nothing but the joy of home-coming to Secret Valley.

That he did not think of the little Carmencita, nor of Rose-alba on the mountain, nor of Tom Storm in Lost Valley or of Black Jack Devlin, was because he didnt know any of them except Tom Storm, and he didnt know that Storm was here. He had run away to go adventuring when a lad of ten.

These, then, by lifes hidden, altogether devious and inscrutable devices, were being led to the converging point. As also were Bob Roberts of the North Star Mine, and an odd chap whom everybody called Hannigan, though his name was something else, and old Romero, a leathern-faced rascal with a pure and romantic heart. Had they known, some of them would have turned their faces in other directionsOr, all being warmly human, would they have nonetheless rushed into the adventure with the fine spirit and devil-may-care abandon of moths into the candle flame?

Quien sabe?