ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: FOLKLORE

Volume 14

SOME DAY BEEN DEY

SOME DAY BEEN DEY

West African Pidgin Folktales

LORETO TODD

First published in 1979

This edition first published in 2015

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1979 Loreto Todd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-84217-5 (Set)

eISBN: 978-1-315-72831-5 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-138-84392-9 (Volume 14)

eISBN: 978-1-315-73075-2 (Volume 14)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

SOME DAY BEEK DEY

West African Pidgin Folktales

LORETO TODD

First published in 1979

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

39 Store Street,

London WC1E 7DD,

Broadway House,

Newtown Road,

Henley-on-Thames,

Oxon RG9 1EN and

9 Park Street,

Boston, Mass. 02108, USA

Printed in Great Britain by

Redwood Burn Ltd, Trowbridge and Esher

Loreto Todd 1979

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Todd, Loreto

Some day been dey.

1. Tales, Cameroon

I. Title

398.2'1'096711 GR351 79-40671

ISBN 0 7100 0024 3

Contents

I should like to express my sincere thanks to Teresa Wamey and the entire Wamey family without whose help this collection could never have been made. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Kenjo wan Jumbam, a good friend and fine story-teller, and to Matthias Che Ngwa who introduced me to Bafut story-telling. It is only fitting that these tales, which are part of the cultural heritage of the Cameroon people, be dedicated to Cameroonians. These three and all who shared their folk traditions with me have my respect, my appreciation and my thanks.

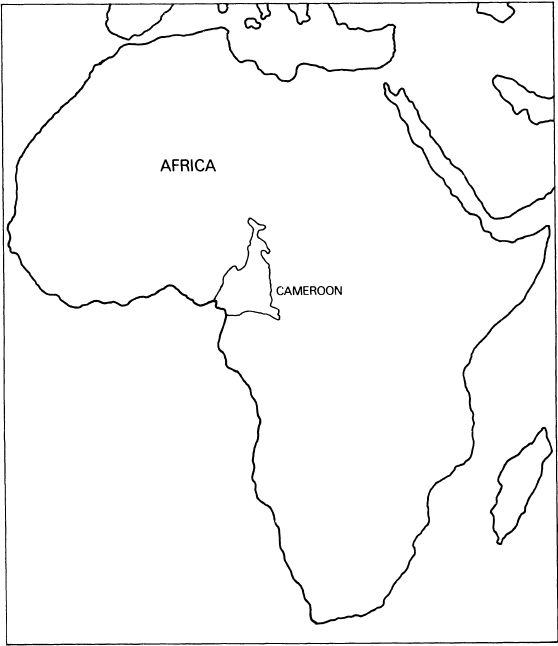

MAP 1 Cameroons position in Africa

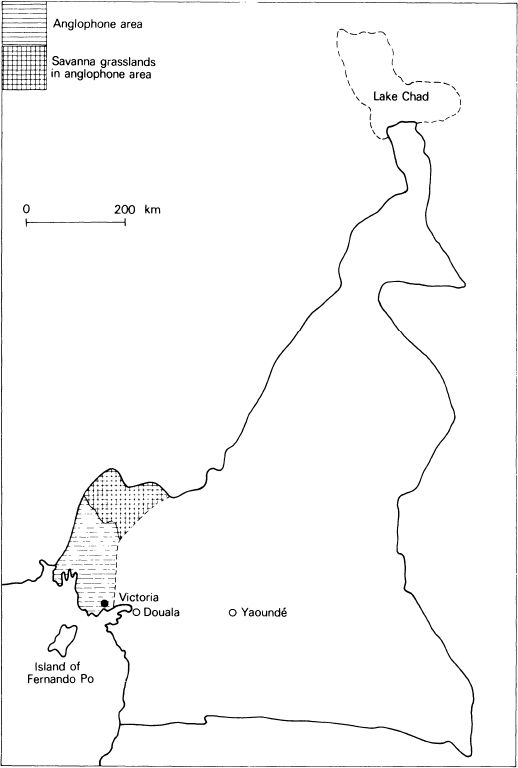

MAP 2 Cameroon showing the anglophone area and the Bamenda Grassfields

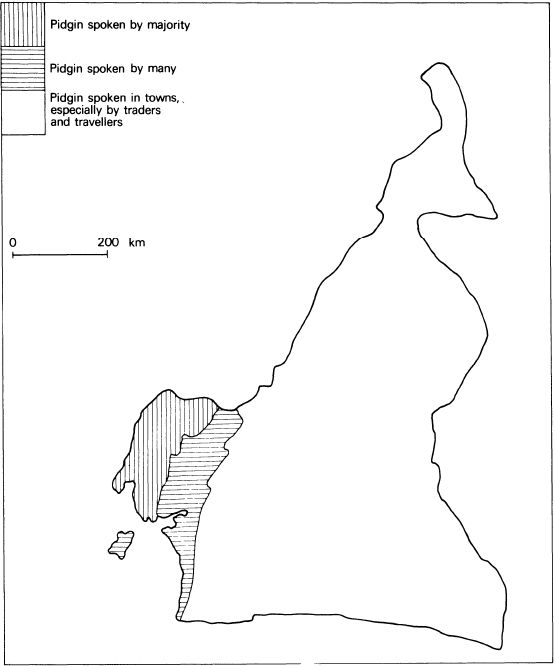

MAP 3 Areas where Pidgin is spoken (Fernando Po included)

There are at least two ways of describing Cameroons location in Africa. Geographers may point out that its 16,000 square miles lie between 2 degrees north and 13 degrees north of the Equator, that it extends from the Bay of Biafra in the south to Lake Chad in the north, that it has a 190-mile coastline, that it is bordered by six states, that it includes within its borders dense, tropical rainforest inhabited by Pigmies, semi-desert inhabited by Fulani and Hausa peoples, and a grassland plateau approximately 4,000 feet above the forest areas. Less scientifically but more evocatively one can think of Cameroon as a hinge between West and Equatorial Africa, as a carrefour de routes, de climats, de races (Soucadaux, 1954, quoted in Schneider, 1963, p.v) and, one might add, as a crossroad of languages.

Many peoples, Bantu and non-Bantu, have visited Cameroon. Some have stayed; others have passed through. Recorded history does not go back any further than 1472 when the Portuguese explorer, Ferno do Po, sailed along its coastline. It may be true, as Mveng suggests (1963, pp.52 ff) that the Greek explorer, Hannon, reached Cameroon in the fifth century BC. Hannon claimed to have sailed the coasts of the Lybic lands beyond the Pillars of Hercules and he described a large, active volcano which he called the chariot of the Gods. Mveng suggests that the volcano in question is the still active, majestic Mount Cameroon which rises straight from the sea to an impressive 13,000 feet. Further research may prove or disprove such a theory but one leaves the realm of hypothesis for that of attested data when one considers the explorations of the Portuguese.

From 1472 onwards the Portuguese made several surveys of the coastal region and indeed Cameroon owes its name to the Portuguese word for shrimps. Early Portuguese explorers witnessed a migration of shrimps and, not recognising it as such, they called the river Wouri Rio dos Camares River of Shrimps (Ardener, 1958, p.533). This usage is first attested on Juan de la Cosas 1509 map of the area. Gradually, the name of Camares was applied to the Douala region and eventually to the whole country. Since the time of the Portuguese the country has been called Kamerun by the Germans, Cameroons by the English and Cameroun by the French. The official Cameroonian policy is to use Cameroon for documents in English and Cameroun for those in French.

The Portuguese did not establish any permanent settlements on the Cameroon coast or attempt any comprehensive exploration of the country, and the British only began to do both in the nineteenth century. From 1827 when they occupied Fernando Po (see ) in an effort to terminate the slave trade they encouraged several Bristol and Liverpool trading enterprises to set up floating hulks as trading posts in the Douala estuary. In 1858 the English Baptist Mission Society established a permanent settlement on the Cameroon coast and called it Victoria. Among the Christian settlers in the new community were men and women from Freetown, Sierra Leone, and their form of creole English, Krio, may well have influenced the pidgin form of English which developed as a lingua franca in coastal Cameroon.

Although a permanent settlement had been established in Victoria and although English-speaking explorers like Lander, Oldfield and Baird had visited the interior of the country in the 1830s and 1840s, Cameroonian contact with native English speakers was very limited. Even in the Baptist missionary establishments where English was used in churches and schools many of the speakers were not British. Some of the founding pastors, men like Joseph Merrick and Alexander Fuller, were descendants of Jamaican slaves and reference has already been made to the Krio speakers who rapidly became important intermediary figures.