This book was published with the assistance of the Tulane University School of Liberal Arts and the Thornton H. Brooks Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2013 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved. Designed by Sally Fry and set in Adobe Caslon Pro

by Rebecca Evans. Manufactured in the United States of America.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clark, Emily, 1954

The strange history of the American quadroon : free women of color

in the revolutionary Atlantic world/Emily Clark.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-0752-8 (alk. paper)

1. Racially-mixed women Louisiana New Orleans History 19th century. 2. New Orleans (La.) Social conditions 19th century. 3. Sex symbolism. I. Title.

HQ1439.N65C53 2013

305.089050976335 dc23

2012042539

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

PROLOGUE

Evolution of a Color Term and an American Citys Alienation

CHAPTER ONE

The Philadelphia Quadroon

CHAPTER TWO

From Mnagre to Place

CHAPTER THREE

Con Otros Muchos: Marriage

CHAPTER FOUR

Bachelor Patriarchs: Life Partnerships across the Color Line

CHAPTER FIVE

Making Up the Quadroon

CHAPTER SIX

Selling the Quadroon

EPILOGUE

Reimagining the Quadroon

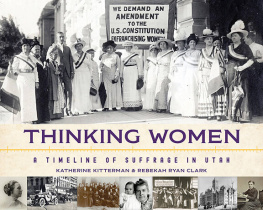

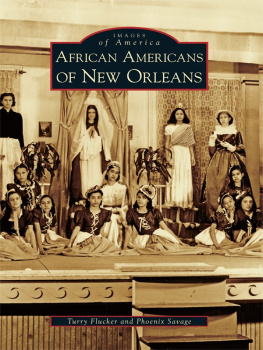

Illustrations

1. Jeffersons racial algebra,

2. Andrs de Islas, De Espaol y Negra: nace Mulata, 1774,

3. Moreau de Saint-Mrys racial taxonomy,

4. Mr. Scratchem,

5. Desalines,

6. Costumes des Affranchies et des Esclaves des Colonies,

7. Free black militiaman,

8. Claiming paternity,

9. Une Mulatresse,

10. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Odalisque with Slave, 1839,

11. The Octoroon, or Life in Louisiana, c. 1861,

12. The Globe Ballroom,

13. The Festive Five,

14. Miss Lula White,

15. Poster for the movie Quadroon (1972),

16. Edouard Marquis, Creole Women of Color Out Taking the Air, 1867,

The Strange History of the American Quadroon

Prologue

Evolution of a Color Term and an American Citys Alienation

Let the first crossing be of

a, pure negro, with

A, pure white. The unit of blood of the issue being composed of the half of that of each parent, will be

. Call it, for abbreviation,

h (half blood).

Let the second crossing be of

h and

B, the blood of the issue will be

or substituting for

its equivalent, it will be

, call it

q (quarteroon) being 1/4 negro blood.

Thomas Jefferson, 1815

Travelers have long packed a bundle of expectations about what they will encounter when they visit New Orleans. Long before jazz was born, another presumably native-born phenomenon drew visitors to the Crescent City and preoccupied the American imagination. The British traveler Edward Sullivan observed succinctly in 1852, I had heard a great deal of the splendid figures and graceful dancing of the New Orleans quadroons, and I certainly was not disappointed.

The Civil War did not much alter advice to visitors about New Orleans quadroons. The southern tour in a guidebook published in 1866 includes New Orleans quadroons in its itinerary. Admitting that the foregoing sketch of society and social life in New Orleans, I need hardly remind my reader, was penned long before the late rebellion had so changed the aspect of every thing throughout the South, the entry reassures its readers that

Passages like these give the impression that New Orleans was the sole place in America where one could encounter beautiful women produced by a specific degree of procreation across the color line, women whose sexual favors were reserved for white men. The reality was, of course, more complicated than that. Women whose racial ancestry would have earned them the color term quadroon lived everywhere in nineteenth-century America.

Sally Hemings ancestry qualified her as a quadroon under Thomas Jeffersons own rubric, but when he sat down in 1815 to clarify to an acquaintance the legal taxonomy of race in his home state of Virginia, he did not take the living woman best known to him as his example. Instead, he eschewed the vivid register of language and enlisted the symbolic representation of algebra to illustrate the genetic origins of the physical and legal properties of the woman who bore most of his children and was his deceased wifes half sister. In a virtuosic and bizarre display of what one scholar has called a calculus of color, Jefferson presented a tidy mathematical formula to define the race and place of the quadroon. The complicated, messy identity and status of Sally Hemings were tamed by the comforting discipline of symbolic logic. Flesh and blood, love, shame,

This formulaic representation renders race as a kind a chemical compound comprising elements that act on one another in ways that multiply, mix, or cancel one another out to produce predictable results. Just as the combination of the elements of hydrogen and oxygen in the proportions represented by the formula 2H2 + O2 = 2H2O will always produce H2O water Jeffersons calculus of race was meant to be precise, immutable, reliable, knowable. With detached precision, Jefferson produced theoretical mulattos and quadroons devoid of the untidy human elements of desire and power that destabilized the living expressions of his mathematical calculations. He may have been driven to abstraction by the disturbing situation of his own reproductive life, but larger historical currents probably played as important a role in his recourse to symbolic logic.

More than two decades before he drafted the chilling equations of 1815, Jefferson produced his well-known observations on race in Notes on the State of Virginia. The black people Jefferson references in Notes are not abstract symbols but corporeal examples, their differences from whites mapped on their bodies and projected onto their sensibilities. The observations in Notes are evocative, almost sensual passages, dense with palpable detail. Here, race is human, organic, expressive, a thing whose qualities can be described, but whose essence cannot be defined. Race slips the porous boundaries of words and threatens to overwhelm with its immeasurable meaning. Jeffersons calculus of 1815, by contrast, imprisons race within the abstract forms and structures of mathematics, subjecting it to universal rules that prescribe and predict comforting certainties that can be anticipated, managed, even controlled.

The dissonance between Jeffersons qualitative disquisition on blacks in Notes on the State of Virginia and his algebraic calculations of 1815 begs questions about more than the incongruities in the mind and life of one man. It points to a widespread and enduring tension in the American imagination over the symbolic expression and meaning of race that intensified and accelerated with the outbreak of widespread, violent slave rebellion in the French sugar colony of Saint-Domingue in 1791. Jeffersons own disquiet over the events that convulsed Saint-Domingue for the next thirteen years is clear in his correspondence, public and private. He spared his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph none of his fearful assessment in the early months of the violence. Abundance of women and children come here to avoid danger, he told her in November of 1791, having written to her earlier that the slaves of Saint-Domingue were a terrible engine, absolutely ungovernable. He gave full vent to the enormity of his fears to his colleague James Monroe two years later. I become daily more and more convinced that all the West India Island will remain in the hands of the people of colour, and a total expulsion of the whites sooner or later take place, he wrote in the summer of 1793. It is high time we should foresee the bloody scenes which our children certainly, and possibly ourselves (south of the Potomac), have to wade through and try to avert them. Later that year he wrote to Governor William Moultrie of South Carolina to warn him that two Frenchmen, from St. Domingo also, of the names of Castaing and La Chaise, are about setting out from this place [Philadelphia] for Charleston, with design to excite an insurrection among the negroes. These men were neither former African captives nor French migrs dedicated to the cause of racial equality, but the products of sexual relations between the two. Castaing, Jefferson advised Moultrie, is described as a small dark mulatto, and La Chaise as a Quarteron, of a tall fine figure.

. Call it, for abbreviation, h (half blood).

. Call it, for abbreviation, h (half blood). or substituting for

or substituting for  its equivalent, it will be

its equivalent, it will be  , call it q (quarteroon) being 1/4 negro blood.

, call it q (quarteroon) being 1/4 negro blood.