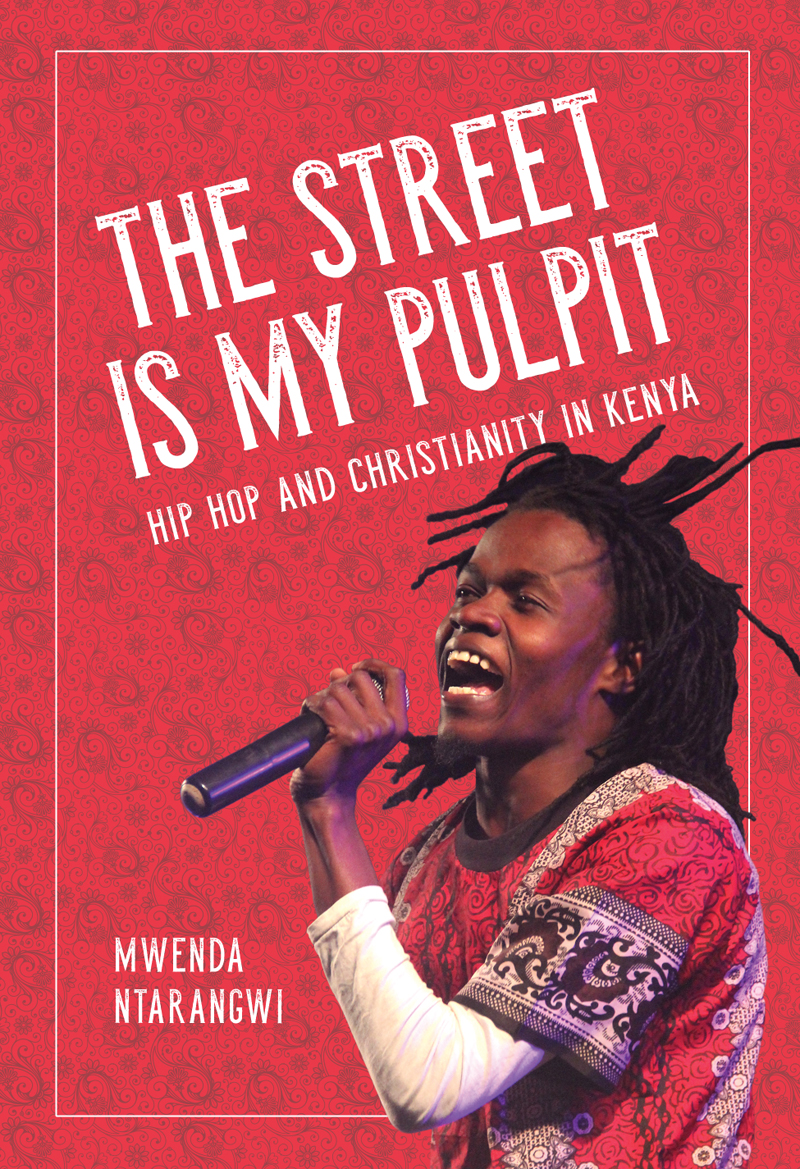

THE STREET

IS MY PULPIT

INTERPRETATIONS OF CULTURE IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM

Norman E. Whitten Jr., General Editor

A list of books in the series appears at the end of the book.

MWENDA

NTARANGWI

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

URBANA, CHICAGO, AND SPRINGFIELD

2016 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ntarangwi, Mwenda, author.

Title: The street is my pulpit : hip hop and Christianity in Kenya / Mwenda Ntarangwi.

Other titles: Interpretations of culture in the new millennium.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2016. | Series: Interpretations of culture in the new millennium | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016003055 (print) | LCCN 2016005502 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252040061 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252081552 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252098260 ()

Subjects: LCSH : Juliani, 1984 | Christian rap (Music)Kenya. | ChristianityKenya. | Music and youthKenya. | YouthKenyaSocial conditions21st century. | Rap musiciansKenya.

Classification: LCC ML 3921.8. R 36 N 83 2016 (print) | LCC ML 3921.8. R 36 (ebook) | DDC 782.421649112dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016003055

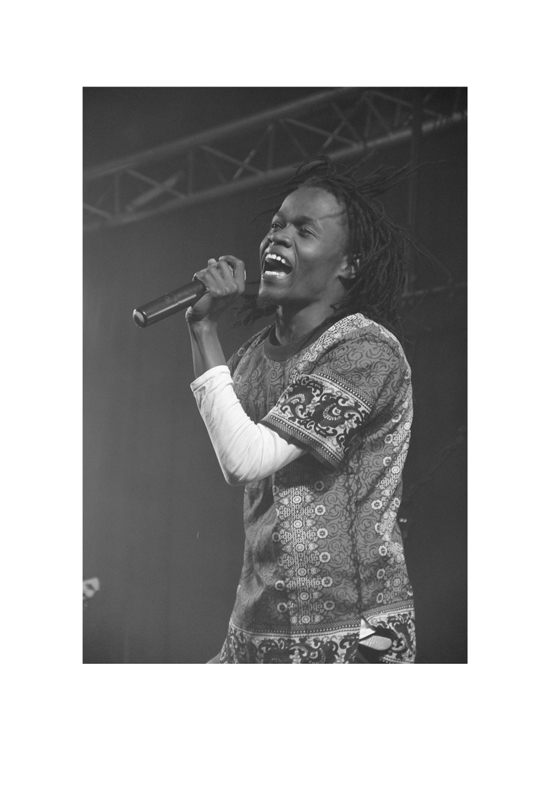

Frontispiece: Juliani in action

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

FOREWORD

When I was growing up in Dandora, a suburb of Nairobi, Kenya, music was my identity. I never saw beyond getting noticed and performing at school outings and joining drama festivals. After high school, music gave me a place in my surroundings. For a young person to be noticed, he or she had to join a gang. To be a member of a gang, such as Kamjesh or Mungiki, back then was the in thing. Later, the more I worked on turning my talent into a skill, the more I got the attention of many people, including those at Mau Mau Camp, a group of rappers famed for speaking on what was happening politically and socially in society, who later welcomed me into the group. At that point, music became more than an identity: it was a skill I had acquired. From a skill, music became a career, especially after getting paid a couple of times for appearances and getting invites to performances in various platforms.

I knew I was good at what I did; I knew I was one of the best rappers among my peers, but I had this feeling that always disturbed me. I knew there was more to it. So in 2005 I was born again and became a Christian. I knew it was the right decision, but a lot was still not clear. Reading the manuscript for this book gave me a lot of answers, and things started making sense, especially after my interaction with Professor Ntarangwi.

My contribution to the music industry and my belief are aligned to a higher purpose. Hip hop isnt just a genre, and the expression of my faith isnt just my style and personality. Pulpit Kwa Street , the title of my second album, is synonymous with the great commission given to Christians in Matthew 28:1920, Go out and make disciples. If I am going out to make disciples, then the only thing that doesnt change is the authority I am given; the tools and packaging of the message have to be within the surrounding culture, and we must not distort the message.

My background in music is mostly from the Mau Mau Camp. My background is socially conscious music built by my conviction of faith. Normal conscious music just captures what is happening and is without a solution or way forward. Through the projects I support, I try to provide not just the message but actions to make a difference. Since 2005 when I was born again, my music has been spiritual and conscious, which was later confirmed to me when I read Isaiah 58. I like using imagery I find around me to explain the spiritual truth I present in my songs.

Juliani (Julius Owino), Nairobi, July 2014

PREFACE

This is a book about hip hop music as it is composed and performed by a Kenyan artist named Juliani (Julius Owino). Juliani is a Christian, and it is his identity as a Christian that gives weight to the analysis carried out in this volume. This book is also about ethnography, the kind of ethnography that is only possible when carrying out research on a transient entity, such as popular music. It is about the nature of collaboration that shapes all ethnographies: collaboration between the researcher and those being researched upon. It is also a book about me as the ethnographer, my own subjective identity that is deeply tied to the topic of research and the process of research. Ultimately, this is a project about a slice of life that the hip hop music of a single artist represents and that is used as a window into the workings and reconfigured frames of what it means to be Christian in contemporary Kenya, especially for the countrys growing youth population. Methodologically, it is a work full of collaboration and intersections, as I rely upon Julianis own story about his music, life, and Christian faith.

This book is a result of a long scholarly journey into popular music that began in the late 1980s. At the time, I was one of a few Kenyan high school graduates who secured a spot in the similarly few public universities that stood at the top of our elitist education system. It was also a time when we experienced a rapid spread of (mostly) US and European popular culture through music, film, and magazines that we all wanted access to for a glimpse of life overseas. But, more specifically, our hearts and imagination had been captured by the break-dancing craze that was sweeping across the popular culture universe at the time. We, therefore, sought to define our identities not only within our new intellectual context of the university but also the larger world such media availed to us. Little did I know break dancing would be a key marker of what would become my own study subject almost two decades later.

This book is an attempt to capture a genre of music born out of that breakdancing craze I participated in as a young university student in Kenya. It is also a project that brings to the fore another part of my own identity, my Christian faith, that seeks to cultivate enough critical distance to articulate its workings and expressions as embodied in the public via hip hop music. This volume is, much like many other prior scholarly works I have undertaken, a combination of subjective and objective analyses of cultural practices and expressions that I have observed and experienced. It is a book about youth participation and production of hip hop as a productive medium through which to explore multiple practices and meanings expressed within contemporary Christianity in Kenya. I see a kind of expressive glue bonding these two otherwise seemingly different genres of public life. As a form of religious expression, Christianity has an intrinsic tendency to produce a kind of moral and purposeful individualism that leads the individual to focus first on a personal relationship with God and then an individualized reward or punishment in the afterlife. Similarly, hip hop has a tendency to focus on the individual, the musician, as the storyteller, and the sound and lyrics as an embodiment of a specific kind of individualized expression. And, yet, both are geared toward a corporate audience with a goal of providing some form of influence.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.