Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

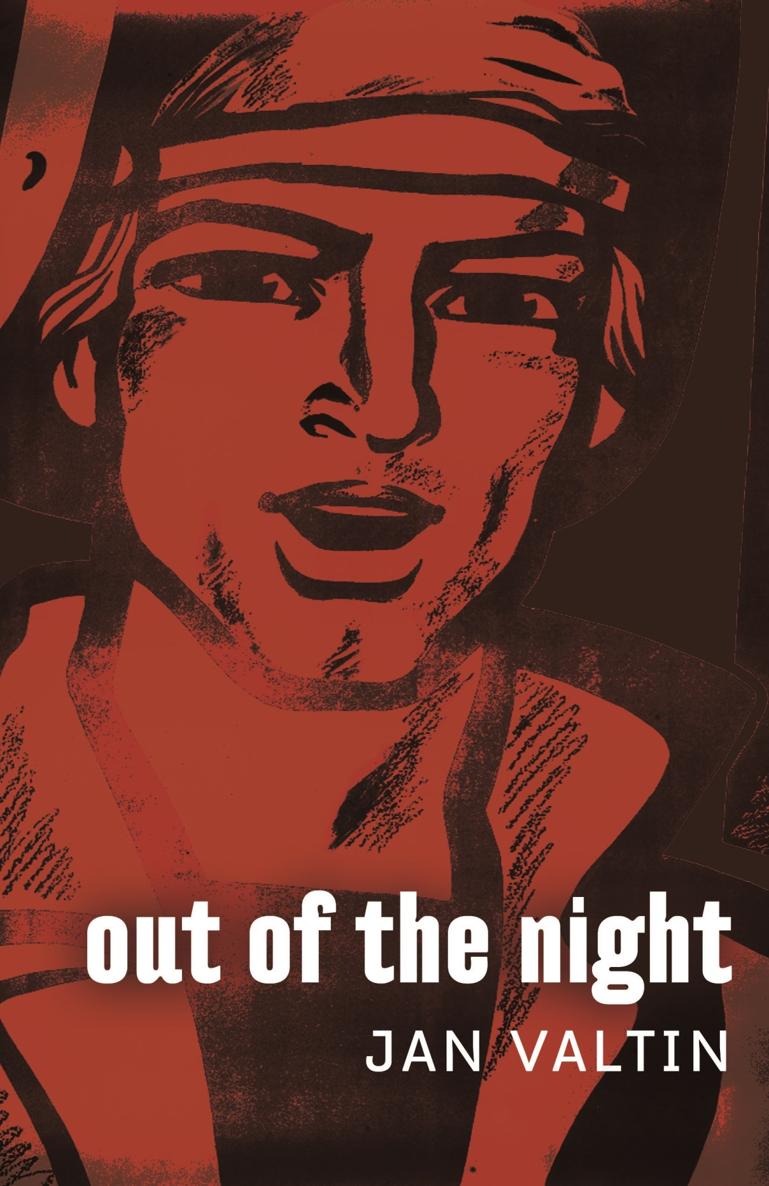

OUT OF THE NIGHT

Jan Valtin

Out of the Night was originally published in 1941 by Alliance Book Corporation, New York. Jan Valtin, also author of Children of Yesterday , is an alias of Richard Julius Herman Krebs.

Chapter One LUMPENHUND

I am a German by birth. But the years of my childhood were scattered over places as far apart as the Rhine and the Yangtze-kiang. My voyage began at the point where the Rhine suddenly sweeps westward to bite its course through the mountains before it curves north again to flow, broad and swift, past the Lorelei and the towers of Cologne. One day in 1904 my mother, then on the way from Genoa to Rotterdam to join her husband, who had come in from the sea, felt that her time was near at hand. She interrupted her journey and went to the home of people who knew her, in a little town near Mainz. There she gave birth to her first son. And before I was one month old, she carried me aboard a steamer, bound down the Rhine to Rotterdam.

My father had spent most of his life at sea. But despite his roamings, he had the devotion of a wanderer for the land of his birth, a devotion which I did not learn to share. During the decade preceding the World War my father was attached to the nautical inspection service of the North German Lloyd, in the Orient and in Italy; it was a shore job which allowed him to take his family from port to port at Company expense. One result of this nomadism was that by the time I was fourteen I spoke, aside from my native language, fragments of Chinese and Malay, and had a smattering of Swedish, English, Italian and the indomitable Pidgin-English of the waterfront. Another upshot was that I acquired early a consciousness of inferiority toward boys who had had the privilege of experiencing their boyhood in one country. In the face of the challenging bigotry of those who had taken rootThis is my country; it is the best country,I felt a certain sad instability. I retaliated by regarding with a childish contempt the healthy manifestations of nationalism.

Invincible wanderlust was another result of our life on the waterfronts. I ran off on hot afternoons to explore the harbors and to watch maneuvering ships and toiling stevedores. I knew the smells of godowns and of ships holds; when the wind stood right 1 could distinguish the aroma of jute or copra or tropical woods a quarter of a mile away from the wharves. I liked to read books of exploration and bold voyaging. I never played at being a soldier. I was either a skipper, a boss of longshoremen or a pirate. I liked to sail the little boat I had when I was twelve through squally weather in the estuaries of the rivers Weser and Elbe. I had my proudest moment when the master carpenter at the boatyard pointed me out to a colleague with the words, That curly-head, he sails like the devil.

My father rarely spoke of his adventurous past of which tattooings of anchors, barques, and exotic wenches with enormous hips on his arms and body, as well as ponderous silver decorations bearing the Chinese dragon and the Persian lion, gave an inkling. Like most German craftsmen of the period, he was conservatively class conscious. He belonged to the Social Democratic Party, was a loyal trade-unionist, and considered the Kaiser as a superfluous clown. He was militant in a quiet way, yet capable of sudden eruptions of temper, and he firmly believed in a just and beautiful socialist future.

My courageous and deeply religious mother had a dream of her own: a house on some hill, with a garden and a sprinkling of birches around, a friendly anchorage to which her four sons, all of whom were destined to follow the sea, would flock for a holiday after every completed voyage. She was a native of Schonen, the southernmost province of Sweden, and she shared the natural hospitality and a respectful love for all growing things which seem to be the characteristics of the Swedish.

The first school I attended was the German school of Buenos Aires. I remained there but a little over a year, and my memory of it is vague. Two years at a British school in Singapore followed. It was here, in an atmosphere of equatorial heat and British world domination, that I first became aware, shamefacedly, of the vast gulf which separated me, the child of a worker, from the sons and daughters of colonial officials and the white merchants of the East. I had no access to their parties, and the bourgeois arrogance of their parents made them shun the humble home of my family. We had but two Chinese servants, while they had fifteen and twenty. Because my father saw no harm in my association with the off spring of his industrious Eurasian aides, the little imperialist snobs of my class coined a nickname for me which even made some of the grown-ups smile. It was Lumpenhund, which means ragged dog. I was awkward and too big for my age. The teacher, a genteel but slightly battered Englishwoman, suspected, I fear, that her discriminations against her only proletarian pupil and her genuflections before the sires of the well-to-do escaped my attention.

In 1913 my father was transferred to a temporary job in Hong Kong, and later the same year he was called to supervise the outfitting of newly-bought ships in Yokohama and Batavia. In all these travels his family went with himtraveling second or third class on chance steamers of the North German Lloyd. I well remember the officious deck steward of the liner Kleist who hustled me from the promenade deck to a deck considerably nearer the waterline.

Sei nicht traurig, my father had consoled me. Wir sind nun eimnal Menschen der zweiten Klasse.

People of the second class! The family grew larger from year to year. A sister was born in Hong Kong. Another aboard a ship between Suez and Colombo. A brother was born in Singapore; it was he who later became an officer in the Nazi air force to find his death through an act of communist sabotage in 1938.

The year 1914 saw us in Genoa, Italy, where the company needed an expert on stowage to help the agent in charge in the dispatching of the so-called macaroni liners, the huge ships of the Berlin type engaged in carrying vast numbers of Italian emigrants and harvest hands to New York and the South American wheat and beef metropoles. It was in Genoa that the War overtook us. German shipping came to a standstill.

We continued to live in Genoa until Italy declared war on Germany in the following year. The intervening nine months savored of a protracted nightmare. They taught me what mass hatred and chauvinism in its ugliest forms could be. Every news kiosk was plastered with pamphlets and posters showing German soldiers nailing children to tables by their tongues, or tearing out the tongues of beautiful young women. I could not go into the harbor, which held for me a fascination I am at a loss to explain, without being assaulted and trounced by bands of Italian hoodlums. On the way to and from school, and even in the garden adjoining our cottage on the slope of the Righi, I and other boys suspected of being German, were bombarded with stones and manure of mules, beaten with sticks, spitten into our faces and hounded even through the broken windowpanes of our homes. I had little respect for Italian boys as fighters. Banded together and armed with solid clubs, six Austrian, Swiss or German boys could easily, I believed, put ten times their number of youthful salita wolves to flight.