PETER CARTWRIGHT, LEGENDARY FRONTIER PREACHER

Peter Cartwright, Legendary Frontier Preacher

ROBERT BRAY

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

URBANA AND CHICAGO

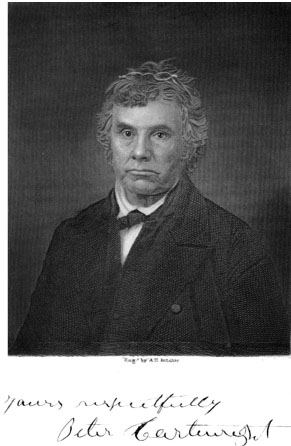

Frontispiece: Peter Cartwright at age seventy.

2005 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

C 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bray, Robert C.

Peter Cartwright, legendary frontier preacher / Robert Bray.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-252-02986-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Cartwright, Peter, 17851872. 2. Methodist ChurchUnited StatesClergyBiography. I. Title.

BX8495.C36B72 2005

287'.6'092dc22 2004029692

In Memoriam: Minor Myers Jr. (19422003)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

An early working title of this book, Greater than the King, came from a phrase in an 1869 article in Zions Herald, a Boston publication of the Methodist Episcopal Church. The author of the piece noted that in every institution, from royal courts to republican governments to Christian churches, there were those rare figures who were greater than the king. While not having received the final preferments of their organizations, such men were nonetheless their most powerful and influential members. According to Zions Herald, Peter Cartwright (17851872), the humble-born and uneducated pioneer circuit rider of Kentucky and Illinois, was, both within the Methodist Episcopal Church and in the national imagination, somehow greater than all the churchs prelates. In idea and fact, this elusive somehow is what I have tried to capture in the life of Peter Cartwright.

Any biography of the man must be a fencing-match with his Autobiography (1856). It is a classic of Americana and the source of most of the stories that have contributed to Cartwrights folkloric reputation as a western frontier hero. Another way of putting this is to admit that much of what we believe we know about the subject is based on what he chose to remember in that single book. I have therefore subjected the Autobiography to a skeptical analysis, matching its claims, wherever possible, against the sketchy documentary record. And I have striven to fill in the personal and political silences in the Autobiography by providing a context wider than American Methodism. For Cartwright was deeply involved with important national issues such as slavery, and for more than twenty years (beginning in 1832) he was a political, social, and religious antagonist of Abraham Lincoln. Finally, he was also a redoubtable man of words in preaching and debate and a writer (though he denied any gift as such) whose best-selling book has proved a lasting contribution to antebellum U.S. literature.

In my account of Cartwrights Kentucky years, I have relied on the foundational research of Theodore Agnew, whose 1950 Harvard dissertation was the first scholarly study of the preachers earlier life. Brian Hohlts more recent dissertation on Cartwrights Illinois political career (St. Louis University, 1998) has been immensely valuable. The Great Rivers Conference United Methodist Archives in Bloomington, Illinois, now located at Macmurray College, Jacksonville, Illinois, holds important documents relating to Cartwrights nearly fifty-year ministry in Illinois. The Great Rivers archivist, Catherine Knight, has unstintingly helped me find what I sought in her collection, for which I am most grateful. And thanks also to the conference historian, Richard Chrisman, who taught me the complexities of Methodist Church polity in the Illinois Conference. Three eminent Lincolnists have helped me understand the complex interaction between Cartwright and Abraham Lincoln: Rodney Davis and Douglas Wilson of the Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois, and Michael Burlingame, late of Connecticut College. John Hallwas, of Western Illinois University, has read the manuscript twice, offering excellent advice each time. Two devoted editors at the University of Illinois Press have seen this long project through: Richard Wentworth from the start, and Judith McCulloh, who has recently pushed me toward the finish line. Finally, my own institution, Illinois Wesleyan University, has generously supported the research, writing, and publication of this book through its faculty development grants program.

PROLOGUE

Virginians

Farewell, my friends, Im bound for Canaan,

Im traveling through the wilderness

Parting Friends, John G. McCurry

Born, he said long after, in Amherst County, September 1, 1785. And born again at a frontier Kentucky revival in 1801 (3738). Vague about Virginia, as he would be vague about Kentucky and Illinois, indeed about most places and persons, particularly himself, he spoke in passing of an early boyhood somewhere on James River near the Blue Ridge, ensuring that anyone looking for the spot would have the devil of a time finding it. The sole property of record for the family was a poor piece of upland, barely held, described in the plat book according to its metes and bounds:

a parcel of Land Containing forty Acres (be the same more or less) Lying and being on the Branches of Purgatory below Findleys Gap bounded as followeth to witt Beginning at pointers Corner to William Cabell and Richard Murrow & running thence on Jessee Martins line North Sixty five Degrees East sixty poles to a Red Oak, thence with a line of Marked Trees fifty eight poles crossing a Branch to a small Red Oak and Pointers in the Old Line, and with it south twenty two Degrees West one hundred and Eleven Poles to Pointers in William Cabells line & with it South twenty three poles to the begining.

Not much of a farm if farmed at all. Forty acres more or less, and no evidence of a mule. But plenty of scrubby trees, more than they could ever clear or use; fields of rocks that sparked and snapped the plowthird-rate land, bought and sold by speculators hoping someone like the Cartwrights would come along. Subsistence in the 1780s: broadax ringing down the valley, slash and burn, smoke and ash; lowing, manuring cattle; noonday scream of wheeling hawk; a crying in the cabin. And behind these, never still, heard in the quiet, the burble and seep of Purgatory, that swampy creek sliding to the James.

No, not much of a place, even for the Piedmont, foot of the mountain, hindquarter of Virginia society. They had come about as far from cavalier gentility as they could and still stay on an eastern watershed, still within the Old Dominion. If they despised the big planters, who had the best land and the most slaves, they also envied and wanted to emulate themand could not, from lack of acreage, slaves, and money. So, like Jefferson from Monticello, after the Revolution they looked west, fancying that real liberty lay beyond the washboard of receding blue ridges, a world away from the stinking salt smell of the Tidewater. KentuckyKain-tuckCanaan. Now there was a notion for a new nation, a hopeful gleam in Peter Sr.s eye, since the boy was born, and one that wouldnt go away no matter how hard he blinked and rubbed. Why stay here, he thought, when I can be an over-the-mountain man, for which he had the makings if not the means: boyhood woodcraft perfected during the late war, his rifle and a mans Republican discontent in the after years; poor and poorly landed (some would say forever shiftless in a shifty, shifting country, but to his son forever an unnamed buckskin hero), with just a western land warrant and a cache of war stories to show for his Revolutionary service.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.