John I. Anderson

War Dogs of the World War

Published by Good Press, 2019

EAN 4064066168506

To those who love dogs, those faithful friends of mankind, I commend this booklet.

The Author

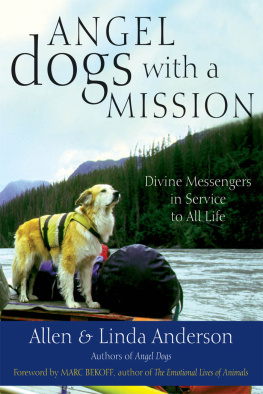

Dogs trained at Neuilly-sur-Seine, near Paris, for service in the French Army.

To The Reader:

Table of Contents

In the city of Neuilly, just across the River Seine from Paris, lives a remarkable woman, Countess Mary Yourkevitch, a Russian by birth, French by adoption. She has for many years devoted her life and spent her income in the interest of the friendless horse, dog and cat. No provisions being made by the French Government and municipal authorities, these homeless dumb animals are left to shift for themselves in case of sickness or distress. She organized the Blue Cross Society of France and for many years has been the President of this Society. She secured grounds in a secluded spot of Neuilly and thereon erected suitable buildings for the housing and care of her homeless and suffering friends. Previously a social leader, she has during these latter years relinquished all social functions and thrown heart and soul into this commendable work of relief.

In 1914, when France was drawn into what was to become a world war, she set about to aid her adopted country. Dogs of all breeds and descriptions were gathered into the Refuge in Neuilly. A systematic training school was organized to fit these dogs for war work, some for the Red Cross, some for trench work, and still others to become messengers to carry important documents and light burdens. It was most essential that a dog for each division of this work should be thoroughly trained, and after this was accomplished the work became one of routine and practice. The trained dogs became the instructors, and it was a stupid pupil indeed that did not become more or less proficient in the work set for it in the course of a week or ten days. To watch this training process is most interesting. A green dog, that is, one without any training, is attached by a short lead to the dog instructor. The command is given to perform a certain duty and at once the trained dog is off on his mission, pulling the untrained dog with him. This is repeated time and again until the pupil learns the word of command and the execution of the same. It is but a question of a few days until the green dog has learned his lessons, and he himself becomes an instructor to some new arrival at the home.

Six hundred dogs were thus instructed for their various war duties and sent to the front. The war is now at an end, and while many of these faithful creatures paid the supreme sacrifice, hundreds are left, some crippled for life, and all in need of proper care for the balance of their lives. During my three months stay in Paris following the armistice, dozens of these dogs were returned to the Countess to be cared for. Knowing the burden placed upon her, both in a financial and physical sense, I am writing this story of the heroic deeds of these wonderful animals. Every penny derived from the sale of this booklet will be devoted to assist this noble work of the Countess Yourkevitch of Neuilly, France.

THE DOGS MANIFOLD DUTIES AT THE

BATTLE FRONT

Table of Contents

The stories of the devotion of dogs to their masters under the most trying conditions of the battlefront form one of the epics of the great struggle.

It is said that there were about ten thousand dogs employed at the battle front at the time of the signing of the armistice. They ranged from Alaskan malamute to St. Bernard, and from Scotch collie to fox terrier. Many of them were placed on the regimental rosters like soldiers. In the trenches they shared all the perils and hardships of the soldiers themselves, and drew their turns in the rest camps in the same fashion. But they were always ready to go back and it is not recorded that a single one of them ever failed when it came to going over the top.

The Red Cross dogs rendered invaluable service in feeding and aiding the wounded. Each one carried a first-aid kit either strapped to its collar or in a small saddle pouch. When they found a soldier who was unconscious, they were taught to bring back his helmet, handkerchief or some other small article as a token of discovery. Many of them learned wholly to ignore the dead, but to bark loudly whenever they came upon a wounded man.

Not only did the dog figure gloriously as a messenger of mercy in the war, but did his bit nobly as a sentinel in the trenches. Mounting guard at a listening post for long hours at a stretch, ignoring danger with all the stolidness of a stoic, yet alert every moment, he played an heroic role.

Full many a time it was the keen ear of a collie that first caught the sound of the approaching raiding party. And did he bark? How natural it would have been for him to do so! But no, a bark or a growl might have told the raiders they were discovered, and thus have prevented the animals own forces from giving the foe a counter-surprise. So he wagged his tail nervouslya canine adaptation of the wig-wag system which his master interpreted and acted upon, to the discomfiture of the enemy.

Often whole companies were saved because the dog could reach further into the distance with his senses than could the soldiers themselves.

It was found that many dogs would do patrol and scout duty with any detachment. But there was another type of dog worker needed in the trenchesthe liason dog, trained to seek his master whenever turned loose. Amid exploding shells, through veritable fields of hell, he would crawl and creep, with only one thoughtto reach his master. Nor would he stop until the object of his search was attained. Many a message of prime importance he thus bore from one part of the field to another, and nought but death or overcoming wound could turn him aside.The National Geographic Magazine.

THE MESSENGER

Table of Contents

Early in the war the Germans realized the importance of gaining possession of the French Coast of the English Channel, and thus cut off communications with England and prevent the landing of English soldiers on French soil.

The Germans selected Ypres as the point of their offensive and the English were strongly resisting the drive. Men on both sides were being mowed down by shell and shrapnel. For many hours the incessant conflict raged, at one time the Germans gaining vantage positions but to give way before the bull-dog tenacity of the English. The strong reinforcements on the German side convinced the commanding officer of the English defensive that it must be a question of short duration until the Germans would achieve the desired objective, and they (the English) would be compelled to retreat. The situation was a critical one and unless the English were reinforced, the day would be lost and the enemy would have a clear way to Calais.

Lying four miles to the rear were two divisions of the English army ready to march to their assistance if required. Quick action was necessary, as every moment was golden. For a courier to cover this distance of four miles and reach the commanding officer of the reserves, close to an hour must be required, and no one could tell what this hour might mean to the ever weakening defensive. A message was quickly written and a messenger dog called. The urgent call for assistance was placed in the bag attached to the dogs collar and he was given the word to go. Just twenty minutes elapsed from the time the dog was entrusted with the message until the officer in command of the reserves had read the hurried call. The camp resounded with the bugle call To Arms and in ninety minutes from the time the message was despatched, the front formation of the reinforcing divisions was in active work. The Germans were driven back with terrible slaughter, and the day was won for the English.