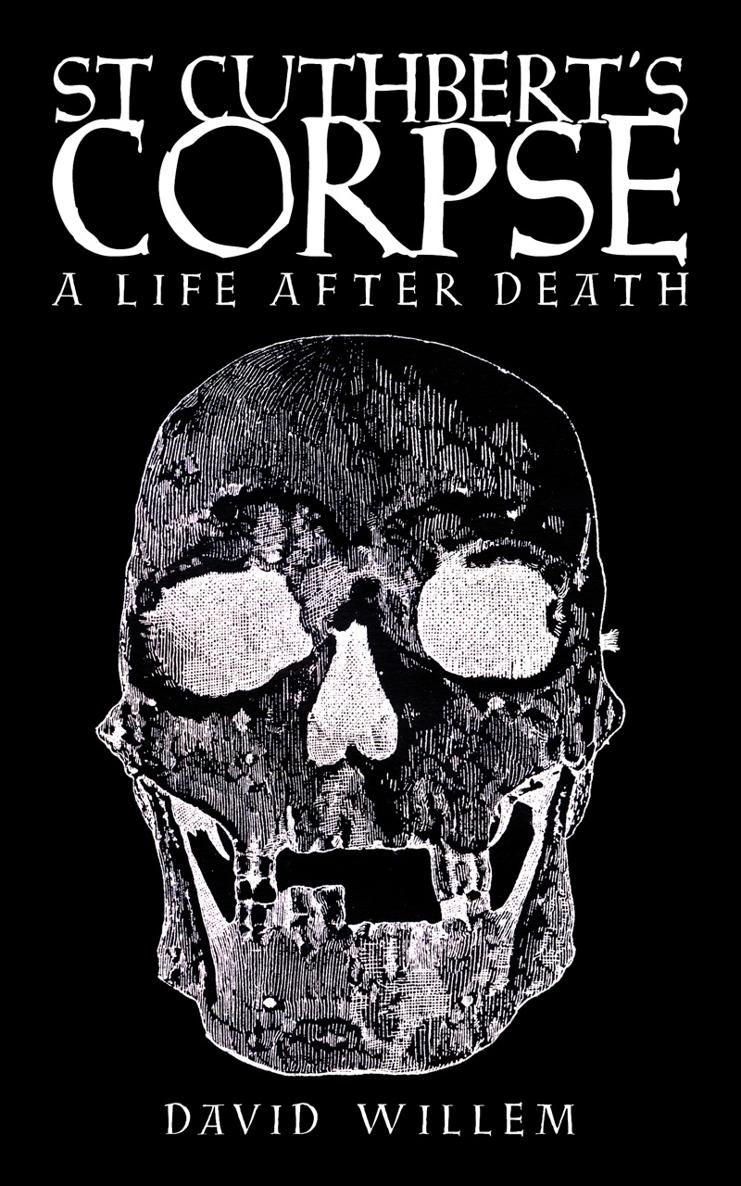

St Cuthberts Corpse

A Life After Death

David Willem

Sacristy Press

PO Box 612, Durham, DH1 9HT

www.sacristy.co.uk

Published in 2013 by Sacristy Press, Durham

Kindle: ISBN 978-1-908381-40-8

ePub: ISBN 978-1-908381-65-1

Copyright David Willem, 2013

The right of David Willem to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, documentary, film or in any other format without prior written permission of the publisher.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher would be glad to hear from them.

Sacristy Limited, registered in England & Wales, number 7565667

Table of Contents

Preface

This started life as a travel book. Like many people who know Durham, I was aware of the story of the founding of the city: how the monks fled Lindisfarne after being attacked by Vikings; how they took with them a coffin containing the miraculously incorrupt corpse of their former bishop, St Cuthbert; and how, as they passed the still-forested site that would become Durham, the cart with the coffin on it got stuck fast in the mire. It would only move when they took the decision to follow a milkmaid and her lost cow towards Dunholmethe monks took this as a sign from St Cuthbert that he wanted his corpse to rest there.

I knew there was a record of this journey from Lindisfarne to Durham, and I thought it might be interesting to follow the route, comparing the world of the beginning of the third millennium with the end of the first. But, as I researched the possibility, I began to realise that there was hardly any detail to compare and that the actual route the monks took was more or less conjectural. At the same time, I started to realise that there was a second, much bigger story obscuring the first: the journey of the corpse through time.

It was in AD 698, eleven years after Cuthberts death, that the monks first discovered that his body had not rotteda miracle that was recorded by Bede, the first historian of the English people. But it intrigued me to learn that this was not the only time that the corpse was examined. On five other occasions, over 1,200 years, the possessors of the corpse took it upon themselves to open the coffin. It happened around 934, after the Viking invasion, in order to mark the resurgence of the Anglo-Saxon kings; it happened in 1104, following the Norman conquest; it happened in 1539, during the dissolution of the monasteries; it happened in 1827, as a part of the Protestant enlightenment; and it happened most recently in 1899, at the dawning of our own democratic, scientific age. This is a list that reads like the chapters in a childs history book from the middle of the twentieth century.

It was almost as if, every few generations, as the axis of the political, religious or intellectual world shifted around them, the people who possessed the corpse felt a compulsion to revisit itto examine it, to associate themselves with its power, and to affirm what remained. And, on almost every occasion the body was disturbed, someone kept a record. Sometimes there are two.

This quickly became the subject of the book. I was excited to lay before the people of the north east, and all those who love Durham, a new perspective on the history of the city and the Cathedral: how both were founded on the miracle of an incorrupt corpse and how the condition of that corpse continued to matter, right into modern times. I soon realised it was also an opportunity to bring together all the accounts of the openings of the coffin into a single volume for the first time.

Beyond this, I have added almost nothing.

Acknowledgements

It was a challenge to come to some understanding of all the material that is available, and it was hard work trying to marshal it all into a coherent narrative. But, as much of the material is not my own, I need to thank many people I have never met, while making it very clear that they bear no responsibility for what follows.

First, I need to thank the late C.F. Battiscombe, a man whose given names I do not even know, but whose monumental, completist Relics of Saint Cuthbert is a volume so substantial that it can only be carried to and from Durhams Clayport Library in a bag-for-life, or a hod. And I have had it on loan on and off for most of the last three years.

Then I need to thank Professor David Rollason. I have read quite a bit of his work, and this has made me so aware of his focused, concentrated intelligence that, despite his being very much alive, I have found it easier not to meet him. I just know that if I did, his fierce, forensic brilliance would reveal the chasms of my vast ignorance of, well, everything he has dedicated his life to. All I can say is that I have enjoyed filling the very, very bottom of some of those chasms with a tiny bit of his scholarship.

Then there are the people whom I havent met whose work has influenced perhaps only a few sentences in this book, but who nevertheless revolutionised my understanding of what was sayable. They are Dr Elizabeth Coatsworth for her essay on Cuthberts golden-garnet cross, and Professor Richard Bailey for his research into the nineteenth-century openings of Cuthberts grave (both of which can be found in Bonner, Rollason and Stancliffes Saint Cuthbert, His Cult and His Community). I also need to thank the late Geoffrey Moorhouse, whose The Last Office helped me understand how the dissolution of the monasteries played itself out in Durham. Finally, in the unmet category, I need to thank Dr Sam Lucy for saying something on the phone that made a huge difference: that three of the other four pectoral crosses that have been found were associated with women.

Then there are the people I have had the nerve to meet and who were much more generous with their thoughts and contacts than I had any right to expect. They were Roger Norris, the former Chapter Librarian at the Cathedral, who helped me scope out the project; Gabriel Sewell, Head of Collections at the Cathedral, who found me a piece of the original Anglo-Saxon coffin to examine (it looks, by the way, like chocolate brownie and smells of old, damp spices); Lilian Groves, the chief guide at the Cathedral, and Seif El Rashidi, coordinator of Durham World Heritage Site, for talking me though everything I couldnt understand; and Dr Giles Gasper for suggesting I contact the publishers and for reading some of the manuscript. I also spent a happy hour with Professor Richard Gameson trying to persuade him that the strap line for the 2013 Lindisfarne Gospels exhibition in Durham should be something like The Book that Made England. I imagine his hour was more frustrating, but he was both charming and incisive in his rebuttal, and I can only say I hope he has forgiven me.

I also want to ask forgiveness of some important dead people. I have spent the last couple of years in the company of the few people who may have actually seen Cuthberts corpse: Fowler, Brown, Kitchin, Raine, Bates, Reginald, Symeon and a couple of anonymous monks. Because my mind has been bending on the same material, I have become attuned to their nuances and little evasions and they have ended up feeling to me a bit like family membersdead ones. So I want to be forgiven, both for this presumption, and for the liberties I have taken re-paragraphing much of their writing. I even re-paragraphed Bede. I certainly would not like it if he re-paragraphed me.