Contents

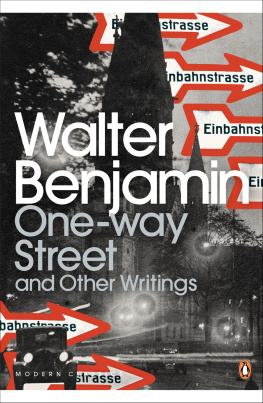

One-Way Street

WALTER BENJAMIN was born in Berlin in 1892 and died in Spain in 1940. He studied philosophy and literature in Berlin, Freiburg, Munich and Bern. After the First World War he worked as a freelance critic and translator, notably of Baudelaire and Proust. He moved to Paris to escape the Nazi takeover and committed suicide in September 1940 while attempting to escape from occupied France to Spain. During his lifetime he was a friend of figures such as Theodor Adorno (with whom he shared many of the ideas expressed in these texts), Bertolt Brecht, Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem.

One-Way Street

and Other Writings

Walter Benjamin

Translated by

Edmund Jephcott

and

Kingsley Shorter

Introduction by

Susan Sontag

This edition first published by Verso 2021

First published by Verso 1979

Updated edition first published by Verso 1997

Verso 1979, 1997, 2021

Introduction Susan Sontag 1979, 1997, 2021

All texts in this volume are included in Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, Bd I-IV

(Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 197476), with the exception of Berliner Chronik

(Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1970)

Suhrkamp Verlag

The following texts first appeared in English, wholly or in part, in Walter Benjamin, Reflections (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978): One-Way Street (selections); On Language as Such and on the Language of Man; Fate and Character; Critique of Violence; Theologico-Political Fragment; The Destructive Character; On the Mimetic Faculty; Naples; Moscow; Marseilles; Hashish in Marseilles; Surrealism; Karl Kraus; and A Berlin Chronicle

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978

All rights reserved

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

USA: 20 Jay Street, New York, NY 11201

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-165-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-166-9 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-167-6 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Benjamin, Walter, 18921940, author. | Jephcott, E. F. N., translator. | Shorter, Kingsley, translator. | Sontag, Susan, 1933-2004, writer of introduction.

Title: One-way street: and other writings / Walter Benjamin; translated by Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter; introduction by Susan Sontag.

Description: London; New York: Verso, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: One-Way Street is a cornerstone of the Benjamin legacy, exhibiting the richness and multidimensional nature of his thought. Included here are his famous essays on the history of Surrealism and photography; the personal and confessional writing on cities in Hashish in Marseille and Naples; and his powerful and fragmented recollections of fin de sicle Berlin; alongside his foundational essays on language, violence, psychology, aesthetics, and politicsProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012987 (print) | LCCN 2021012988 (ebook) | ISBN 9781839761652 (paperback) | ISBN 9781839761676 (ebk)

Subjects: LCSH: Benjamin, Walter, 18921940Translations into English. | LCGFT: Essays.

Classification: LCC PT2603.E455 O54 2021 (print) | LCC PT2603.E455 (ebook) | DDC 834/.912dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012987

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012988

Typeset in Fournier by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays

Contents

In most of the portrait photographs he is looking down, his right hand to his face. The earliest one I know shows him in 1927he is thirty-fivewith dark curly hair over a high forehead, moustache above a full lower lip: youthful, almost handsome. With his head lowered, his jacketed shoulders seem to start behind his ears; his thumb leans against his jaw; the rest of the hand, cigarette between bent index and third fingers, covers his chin; the downward look through his glassesthe soft, day-dreamers gaze of the myopicseems to float off to the lower left of the photograph.

In a picture from the late 1930s, the curly hair has hardly receded, but there is no trace of youth or handsomeness; the face has widened and the upper torso seems not just high but blocky, huge. The thicker moustache and the pudgy folded hand with thumb tucked under cover his mouth. The look is opaque, or just more inward: he could be thinkingor listening. (He who listens hard doesnt see, Benjamin wrote in his essay on Kafka.) There are books behind his head.

In a photograph taken in the summer of 1938, on the last of several visits he made to Brecht in exile in Denmark after 1933, he is standing in front of Brechts house, an old man at forty-six, in white shirt, tie, trousers with watch chain: a slack, corpulent figure, looking truculently at the camera.

Another picture, from 1937, shows Benjamin in the Bibliothque Nationale in Paris. Two men, neither of whose faces can be seen, share a table some distance behind him. Benjamin sits in the right foreground, probably taking notes for the book on Baudelaire and nineteenth-century Paris he had been writing for a decade. He is consulting a volume he holds open on the table with his left handhis eyes cant be seenlooking, as it were, into the lower right edge of the photograph.

His close friend Gershom Scholem has described his first glimpse of Benjamin in Berlin in 1913, at a joint meeting of a Zionist youth group and Jewish members of the Free German Student Association, of which the twenty-one-year-old Benjamin was a leader. He spoke extempore without so much as a glance at his audience, staring with a fixed gaze at a remote corner of the ceiling which he harangued with much intensity, in a style incidentally that was, as far as I remember, ready for print.

He was what the French call un triste. In his youth he seemed marked by a profound sadness, Scholem wrote. He thought of himself as a melancholic, disdaining modern psychological labels and invoking the traditional astrological one: I came into the world under the sign of Saturnthe star of the slowest revolution, the planet of detours and delays.Nineteenth Century, cannot be fully understood unless one grasps how much they rely on a theory of melancholy.

Benjamin projected himself; his temperament, into all his major subjects, and his temperament determined what he chose to write about. It was what he saw in subjects, such as the seventeenth-century baroque plays (which dramatize different facets of Saturnine acedia) and the writers about whose work he wrote most brilliantlyBaudelaire, Proust, Kafka, Karl Kraus. He even found the Saturnine element in Goethe. For, despite the polemic in his great (still untranslated) essay on Goethes Elective Affinities against interpreting a writers work by his life, he did make selective use of the life in his deepest meditations on texts: information that disclosed the melancholic, the solitary. (Thus, he describes Prousts loneliness which pulls the world down into its vortex; explains how Kafka, like Klee, was essentially solitary; cites Robert Walsers horror of success in life.) One cannot use the life to interpret the work. But one can use the work to interpret the life.

Two short books of reminiscences of his Berlin childhood and student years, written in the early 1930s and unpublished in his lifetime, contain Benjamins most explicit self-portrait. To the nascent melancholic, in school and on walks with his mother, solitude appeared to me as the only fit state of man. Benjamin does not mean solitude in a roomhe was often sick as a childbut solitude in the great metropolis, the busyness of the idle stroller, free to daydream, observe, ponder, cruise. The mind who was to attach much of the nineteenth centurys sensibility to the figure of the