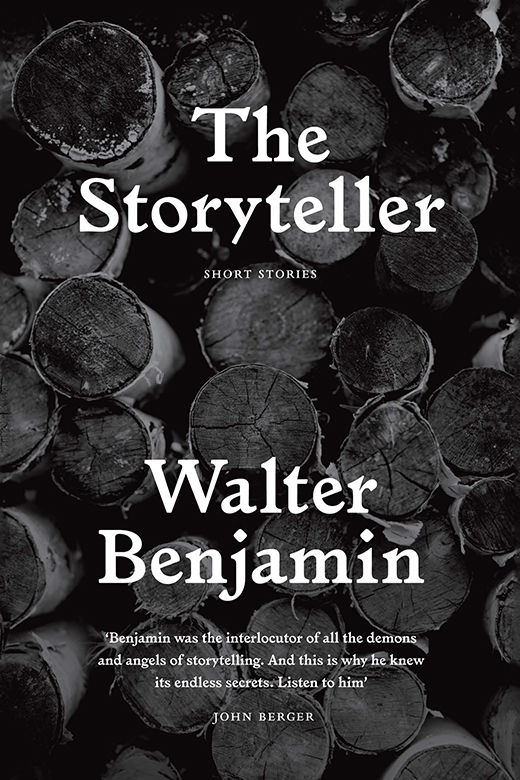

The Storyteller

Tales Out of Loneliness

Walter Benjamin

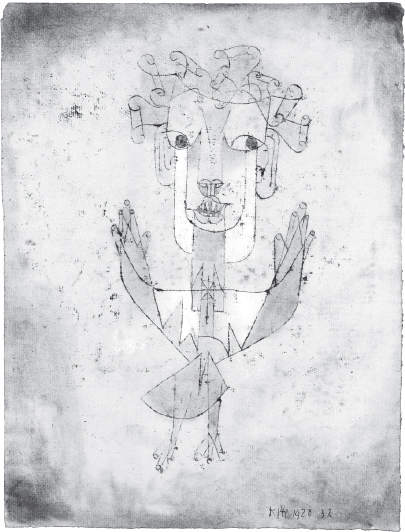

With Illustrations

by Paul Klee

Translated and Edited by

Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie

and Sebastian Truskolaski

First published by Verso 2016

Introduction and Translation Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie

and Sebastian Truskolaski 2016

Translation of Nordic Sea Antonia Grousdanidou 2016

In , Albert Welti, Mondnacht, taken from

Albert Welti, Gemlde und Radierungen, Furche Verlag, Berlin, 1917.

In , Wandkalender Akademie der Knste, Berlin,

Walter Benjamin Archiv.

The images by Paul Klee are in the public domain.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-304-4 (PB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-307-5 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-306-8 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Benjamin, Walter, 18921940, author. | Dolbear, Sam, translator, editor. | Leslie, Esther, 1964 translator, editor. | Truskolaski, Sebastian, translator, editor.

Title: The storyteller : tales out of loneliness / Walter Benjamin ; translated and with an introduction by Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie and Sebastian Truskolaski.

Description: First [edition]. | Brooklyn, NY : Verso, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016013569 | ISBN 9781784783044 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Benjamin, Walter, 18921940 Translations into English. | BISAC: FICTION / Short Stories (single author).

Classification: LCC PT2603.E455 A2 2016 | DDC 833/.912 dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016013569

Typeset in Caslon Pro by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Contents

Walter Benjamin and the

Magnetic Play of Words

Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie

and Sebastian Truskolaski

T hroughout his life, Walter Benjamin experimented with a variety of literary forms. Novellas and short stories, fables and parables as well as jokes, riddles and rhymes all sit alongside his well-known critical writings. He also long harboured plans to write crime fiction. There exists an extensive outline for a novel, to be titled La Chasse aux mensonge, detailing ten possible chapters, including such details as an accident in a lift shaft, an umbrella as clue, action in a cardboard-making factory, a man who hides his banknotes inside his books and loses them.

Charting these continuities is more than a mere exercise in philology. Rather, the purpose of bringing together these texts is to demonstrate how Benjamin formally stages, enacts and performs certain concerns that he develops elsewhere in a more academic register. Consistent across the work is an exploration of such themes as dream and fantasy, travel and estrangement, play and pedagogy. Before commenting directly on the specifics of this topology, however, a discussion of Benjamins reflections on storytelling is warranted.

Benjamin treated the theme of storytelling in an array of texts, not least among them The Storyteller (1936), an essay on the Russian novelist Nikolai Leskov from which the title of the present volume is drawn.

By contrast, the journalistic jargon of the newspaper is the highest expression of experiential poverty a lesson that Benjamin learned from Karl Kraus. By the same token, it would appear that the moment for reading Baudelaires lyric poetry had passed at the time of its publication, yet it is precisely the untimeliness of its presentation that imbues Baudelaires rendition of modern life with the urgency that Benjamin admired. What Benjamin attempts to re-imagine in his engagement with these authors is the communicability of experience in spite of itself. In this regard, it is notable that a common trait of Benjamins own fiction is the layering of voices in imitation of an ostensibly antiquated oral tradition: a sea captain tells a passenger a yarn, a friend tells another friend a curious thing that he experienced, a man tells the tale of an acquaintance to another man, who in turn relates the story to us. These stories create layered worlds of citations, enigmas and perspectives. With this, Benjamin extends a long tradition of recording and retelling stories which stretches from Hebel to Hoffmann and beyond. Here experience finds new ground.

Might it be said, then, that Benjamin is attempting to reactivate the orality of storytelling under new conditions? If so, then what kinds of stories do the trenches demand? What writing speaks to the moment? What follows divides Benjamins literary output into three sections: dreamworlds, travel, and play and pedagogy. Included are a number of reviews which address the themes in each section, focussing the material through a form that Benjamin pushes in extraordinary directions, to the point where it might undo itself.

The first section of the volume clusters around dreamworlds. Presented here are Benjamins own transcribed dreams alongside some of his earliest writings. These early works of fantasy offer visions of a world without pain Focussed here, too, are the erotic tensions of modern city life, a theme Benjamin explored since his earliest writings. The third section presents play and pedagogy as two intertwined aspects in Benjamins thinking. Several pieces explore the play of words, as if to invoke a phrase from Benjamins review of Franz Hessels Secret Berlin words become magnets, which irresistibly attract other words. To learn from and encourage childrens delight at wordplay is axiomatic in Benjamins thinking. In this section is a story titled The Lucky Hand, which features play in the guise of gambling. Is this a modern morality tale? Perhaps Benjamin wishes to convey lessons about instinct and intuition, about the sort of mimetic knowledge possessed by the body? Likewise, On the Minute plays on the idea of learning how to interact with new technologies, specifically radio, another medium in which Benjamin honed his ability to engage audiences through oral presentation. The following pages briefly introduce each of these themes.

Dreamworlds

Benjamins fragments of fantastical fiction number among his earliest writings: Schiller and Goethe, In a Big Old City, The Pan of the Evening, The Hypochondriac in the Landscape and The Morning of the Empress are all thought to have been written between 1906 and 1912.

Long dismissed as mere juvenilia,) Whatever may have caused the widespread disregard for Benjamins early stories they first appeared as an addendum to his Gesammelte Schriften in 1991 after having been omitted from a previous volume dedicated to his Kleine Prosa these pieces are of considerable interest for at least two reasons. For one thing, they distinctively employ certain narrative techniques that seldom appear elsewhere in Benjamins work, for example, the uncharacteristic use of the second- and third-person form. More importantly, however, Benjamins early stories anticipate a number of the theoretical concerns that he developed in subsequent years. Childhood and fantasy, in particular, come to the fore in his fairy talelike prose.