Dear Reader:

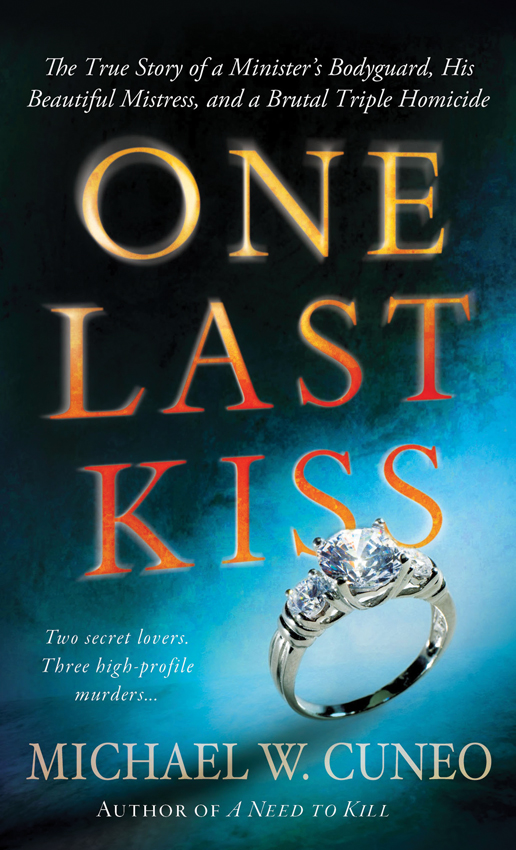

The book you are about to read is the latest bestseller from the St. Martins True Crime Library, the imprint The New York Times calls the leader in true crime! The True Crime Library offers you fascinating accounts of the latest, most sensational crimes that have captured the national attention. St. Martins is the publisher of John Glatts riveting and horrifying SECRETS IN THE CELLAR , which shines a light on the man who shocked the world when it was revealed that he had kept his daughter locked in his hidden basement for 24 years. In the Edgar-nominated WRITTEN IN BLOOD , Diane Fanning looks at Michael Petersen, a Marine-turned-novelist found guilty of beating his wife to death and pushing her down the stairs of their homeonly to reveal another similar death from his past. In the book you now hold, ONE LAST KISS , Michael W. Cuneo examines the details of a horrific family tragedy.

St. Martins True Crime Library gives you the stories behind the headlines. Our authors take you right to the scene of the crime and into the minds of the most notorious murderers to show you what really makes them tick. St. Martins True Crime Library paperbacks are better than the most terrifying thriller, because its all true! The next time you want a crackling good read, make sure its got the St. Martins True Crime Library logo on the spineyoull be up all night!

Charles E. Spicer, Jr.

Executive Editor, St. Martins True Crime Library

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To

Brenda Michelle Cuneo

CONTENTS

A convicted defendant is entitled under American law to appeal his conviction, in an effort to overturn the jurys finding of guilt. As of going to press, an appeal of Chris Colemans conviction in federal court is planned.

PROLOGUE

May 5, 2009

6:43 a.m.

Justin Barlow was sound asleep when his cell phone rang. He reached over and grabbed it on the third ring. As one of only two full-time detectives with the Columbia, Illinois, Police Department, hed grown accustomed to getting calls at odd hours.

It was a neighbor on the other enda guy named Chris Coleman who lived catty-corner to Barlows house in the Columbia Lakes subdivision of town. Coleman said that he was just then crossing the Jefferson Barracks Bridge into Illinois, returning home from an early morning workout at a gym in south St. Louis County. He said that he was concerned about his family. His wife, Sheri, should have been up by then with their two boys, eleven-year-old Garett and nine-year-old Gavin, but no one had answered when hed tried phoning home. He asked Barlow if hed mind going over and checking up on them.

Barlow said sure, no problem, hed go over right away. He could certainly appreciate why the guy might feel concerned. Chris Coleman was head of security for the world-famous Joyce Meyer Ministries, and in recent months hed received some disturbing messages in connection with his job. First there was a series of e-mails sent to his company laptop on November 14 and November 15. And then there were two typewritten letters that he retrieved from the mailbox at the front of his driveway, the first of them on January 2, and the second on April 27. All of the messages threatened terrible harm to Coleman and his family unless he stopped working for Joyce Meyer and publicly renounced her ministry.

Coleman had reported the messages to the police, who in turn had provided increased patrols in the neighborhood. After the second typewritten letter was retrieved from the mailbox, Barlow had taken it a step further. With the help of a colleague from the Illinois State Police, hed installed a video surveillance camera in the window of his three-year-old sons second-floor bedroom. The camera was trained directly on the Coleman house, which meant that anyone leaving an untoward letter in the mailbox was certain to be videotaped.

Barlow slipped out of bed and got dressed, taking care not to awaken his wife and two sons. He put on a pair of cargo pants, a light jacket, his off-duty gun and holster, and his signature Chicago Bears cap. Then he grabbed a portable police radio and contacted the station. He informed the dispatcher where he was going and requested uniformed backup.

He went outside and crossed over to the Coleman residence, which was a white two-story affair located at the end of a winding street called Robert Drive. With its black shutters, brown shingle roof, and attached two-car garage, it looked scarcely different from most other houses in the subdivision. Barlow went to the front door and rang the bell. He waited several seconds and rang again but no one answered. It was a bright, sunny morning, and he could see light filtering into the living room through the shaded window. He looked down the street and saw a squad car approaching.

Barlow was surprised that Chris Coleman still hadnt arrived. When Coleman had called, hed said that he was crossing the Jefferson Barracks Bridge, which was no more than a seven-minute drive away.

* * *

Sergeant Jason Donjon was sitting in the patrol room checking his e-mail when the dispatcher called to him from the dispatch center at the front of the Columbia police station.

Hey, Jason, he said. Come on up here.

Donjon shut down his computer and went up front, where the dispatcher filled him in on the relevant details. Chris Colemanthe same guy whod reported receiving those threatening messageshad phoned Detective Justin Barlow just moments before. Coleman had told Barlow that he was on his way home from a gym in south St. Louis County and was worried about his family, since he hadnt been able to get through to them on his cell phone. Detective Barlow had then contacted the station and requested uniformed backup, saying he was going over to the Coleman residence on Robert Drive to check on the familys welfare.

Donjon went out the rear door of the station and got into his squad car. He turned right onto North Main Street and drove over to the Columbia Lakes subdivision. He made a left onto Robert Drive and parked at the curb outside the Coleman residence. It was now 6:53, ten minutes since Chris Coleman had phoned Justin Barlow.

No answer? Donjon asked, joining Barlow on the front porch.

I rang twice, Barlow said. Maybe theyre in the shower.

Donjon left Barlow on the porch and went to the rear of the house. A basement window was open, its screen leaning against a lawn chair. The grass in the backyard was lush and dewy. There was no indication of anyone other than Donjon himself having walked across it that morning: no footprints, no telltale depressions. Still, the open window was a concern. Perhaps an intruder had somehow managed to get through it without leaving a trail on the lawn. Donjon radioed Barlow, who hurried around to the back of the house.

Barlow looked at the open window, and then he and Donjon exchanged glances. Both men stood there wordlessly for the briefest of seconds. Barlow was the older of the two by several years, a strikingly handsome guy in his early thirties with blue eyes and dark hair. Donjon was soft-spoken and earnest, with a sweet smile and an athletic build. Barlow shined a flashlight through the window. The basement floor seemed clean and dry. There was no broken glass, no grass clippings, no residue of any kind. Donjon radioed dispatch for backup.