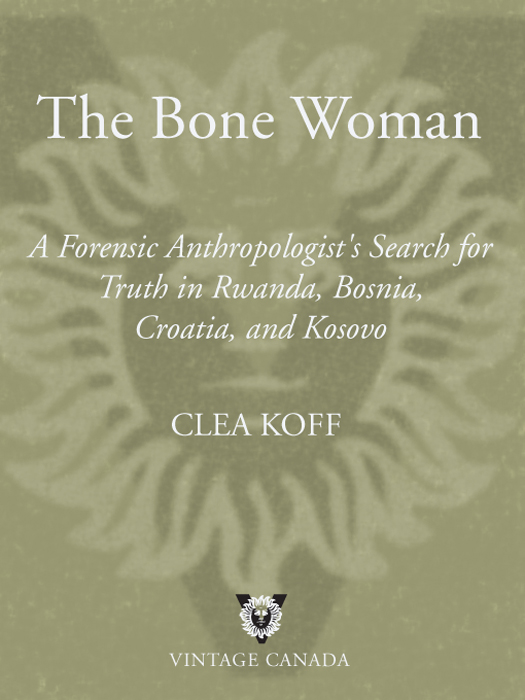

Praise for THE BONE WOMAN

[Koffs] bookindeed, her lifeis a testament to an idealism that shines through a grim, bloody reality.

The Herald ( SCOTLAND )

FascinatingThe overriding impression is of a woman deeply committed to ideals of justice and human rights. In consequence, and despite the extraordinary depravity of the crimes detailed in its pages, The Bone Woman is a humane, hopeful and involving book.

The Guardian ( U.K. )

Honest and effectiveA must-readFew of us could convey the social and scientific complexities of the work as sensitively and effectively as Clea Koff.

The Globe and Mail

This is a brave book, presented in a clear voice by a scientist who is confident that her missions will get to the truth and yet human enough to cry at the horror of it all.

Library Journal

[The Bone Woman is an] attempt to record and confront emotions that had to be kept at bay while more important business was at hand. & There are only a handful of people who have seen and felt (and smelt) what the violence of a new world order has wrought, and [Koff] is one of them.

The Times ( U.K. )

This is a book worth reading both for the inhumanity that is its subject and for the humanity that informs it.

Winnipeg Free Press

A compelling debut that is remarkable for exploring such a harrowing subject in a detached yet compassionate manner, striking a balance between scientific observation and human empathy.

The Scotsman

[Koff] speaks eloquently for the dead. A poignant personal testimony about mans inhumanity to man.

Reuters

Koff has a poets eye in describing her discoveries. Her work does not so much bring resolution to the crime, by uncovering the assailant and having them punished, as restore the humanity to those whose lives were taken.

Times-Colonist (Victoria)

For all its forensic detail, it is Koffs deep sense of connection to the bodies she came to exhume, her unflinching sense of obligation to them, and her willingness to look at what they represent that renders The Bone Woman compelling reading.

The Sunday Times (Australia)

Chilling but mesmerizing Koffs account is neither histrionic nor preachy; its clear-eyed, hard-headed and straightforward. & This book works so well, is so vivid and so moving, because Koff surrounds the dead bodies with living stories.

BookPage

For the seekers of the silvery threads

Acknowledgments

IT IS DIFFICULT to put into words my gratitude toward the following people, but I do know that I was able to write this book because they have been a part of my life: Suttirat Anne Larlarb, Sam Brown, David Koff, Msindo Mwinyipembe Koff, Kimera Koff, Geri Koff, Paul and Gwera Mwinyipembe, Bob Koff, the late Carole Ferry, Amy Uyematsu, Dr. LuAnn Wandsnider, and my grandfather Harry N. Koff, who gave me a book about Pompeii when I was seven and for years after that gave me books on the importance of words and of storytelling, but wasnt here to see what those books inspired me to do.

I thank Isobel Dixon of Blake Friedmann Literary Agency, Patty Moosbrugger of Stuart Krichevsky Literary Agency, and Lee Boudreaux of Random House for making sure that my friends and family were not the only ones to read these stories.

Contents

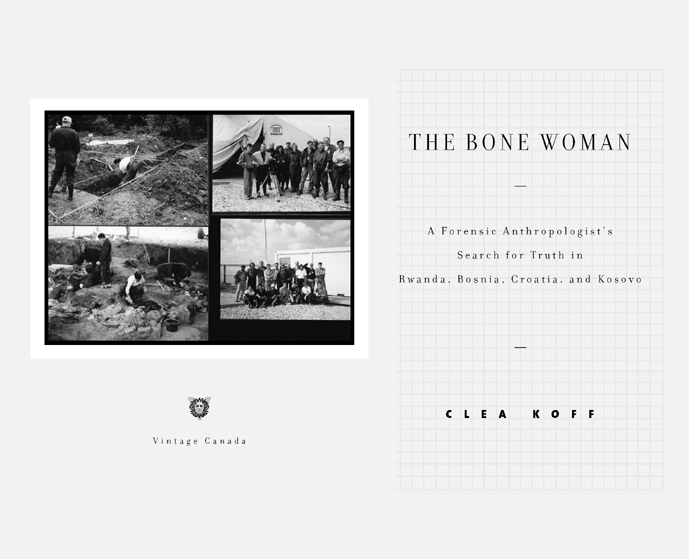

PART ONE | K IBUYE

January 6February 27, 1996

PART TWO | K IGALI

June 3June 24, 1996

PART THREE | B OSNIA

July 4August 29, 1996

PART FOUR | C ROATIA

August 30September 30, 1996

PART FIVE | K OSOVO

April 2June 3, 2000, and July 3July 23, 2000

AT 10:30 IN THE MORNING ON TUESDAY, JANUARY 9, 1996, I WAS on a hillside in Rwanda, suddenly doing what I had always wanted to do. I took stock of my surroundings as though taking a photograph. I looked up: banana leaves. Down: a human skull. To my left: more banana leaves. To my right: a forest of small trees. Directly in front of me: air. I was sitting on a steep slope, in the midst of a banana grove. My knees were pulled up tight to stop me from slipping down; the skull hadnt been so fortunate. It had rolled down to this point from higher up the slope, leaving behind its body. This particular indignity had not been inflicted on this skull alone; indeed, I was surrounded by skulls, surrounded by people who had been killed on this very slope one and a half years earlier. Most of their heads had rolled away since then. I was there to find the heads and get them back to their bodies. After that reunion, we would have a chance at determining age, sex, stature, and cause of death, and maybe even who these people were. I crouched quietly, listening to the skull. It was facedown; so far, I had been able to focus only on the wound to the occipital: a strong blow to the back of the head with something sharp and big. I looked at the wound, the way the bone bent inward, and the V shape of the cut in cross section. A mosquito buzzed by my ear and landed on the rim of the cut on the skull. You wont get much joy there, mate: the bloods long gone from him, I thought, and brushed it away.

The way the skull was resting, I could see the maxillary (upper) teeth. One of the third molars had been erupting when this person was killed. I had just had my own wisdom teeth extracted before leaving for Rwanda and I ran my tongue thoughtfully over the fleshy sockets in my gums. Its interesting how you can immediately look for points of comparison between your own body and the body in front of you. Is it empathy with their plight, or relief that youre still alive? I didnt have time to contemplate this point further, as my body recovery partner, Roxana, came crashing through the leaves to my right, bringing with her Ralph, the photographer who would record the exact location and position of the skull. Next to the skull we rested a photo boardthis provided an identification number as well as the dateand an arrow pointing north. In the silence, we listened to the Nikon shutter open and close, twice.

This done, we could move the skull. I picked it up and turned it to see the face. And there it was in front of me: a tight, deep, diagonal cut across the eyes and bridge of the nose. The cut had broken all the delicate bones that form that identifiable feature on all of us. It was painful to look at, so I put the skull down, exchanging it for a clipboard onto which Roxana and I recorded the condition of the bone, the number of teeth recovered, and the location of the skull on the hillside. When we had gathered all the information, we stabilized the skull where we had found it and ascended the slope, ducking under low-lying banana fronds and sidestepping sun-bleached vertebrae, into a grassy area replete with fragments of clothing. We were looking for our skulls body. After clearing away the grass with our trowels, we found that some of the clothing held bones, partially buried in soil that had eroded from higher up the slope. Was this our man? The search was on.

This search and dozens like it continued for two weeks with varying success. There were four anthropologists scattered about the hillside, all of us engaged in the same task. Meanwhile, two archaeologists were on the crest of the hill, delineating the edges of the feature we would spend two months investigating: the mass grave behind the Kibuye church.