Introduction

The most shocking moment I experienced in writing this book came when someone compared the University of Michigan football program to the New York Yankees.

This staggered me. Not only staggered, but sickened.

I was a well-brought-up child of Detroit, taught by my father that the Yankees were to be regarded as objects of hatred. They were arrogant and soulless in their perfection. They blighted every summer of my life from the time I became aware of baseball until I graduated from college. In those 16 years they won the pennant every season but two. My Tigers bobbed up and down between second-rate play and occasional contention. On those rare instances that they seemed about to challenge the Yanks, they were swatted away like the pesky insects they were.

A college friend said that rooting for the Yankees was like rooting for General Motors. (Of course, given the recent history of GM, that comparison isnt especially apt anymore.)

The lesson learned from those years, however, was that precious moments of intense joy are paid for many times over by years of anguish.

Anguish is not generally a word used in the same sentence as Yankees fan . But you do become closely acquainted with it in Ann Arbor.

I know this because I was also taught by my father to cheer for the Wolverines. I could never quite figure out why he was so attached to them. He didnt go to Michigan, and neither did I. We were both graduates of Wayne State University and proud fans of the Tartars.

Well, at least we used to be. The school grew weary of having its nickname confused with the gunk on your teeth and the stuff you put on fish, so several years ago it changed its name to Warriors. So I am now a proud Warrioryes!

Still, Wayne is a commuter campus, and although it is a major university with excellent professional schools and research facilities, it plays Division II football. I have attended exactly two Wayne State football games in my life. One was to meet a girl in 1960, and the other was to cover a contest at Eastern Illinois in 1967. They lost both times, and the girl wasnt that great, either.

Faced with this vast emptiness in my collegiate loyalties, I followed Dads example and turned to Michigan. I was nine years old at the time, and that Michigan team happened to go to the Rose Bowl and beat California.

This indicated to me that I had chosen wisely. Not that I was all that wrapped up in it. Neither the infamous Snow Bowl game of that 1950 season at Ohio State nor the ensuing Rose Bowl was televised. Still, I do have a vague recollection of listening to the game in Pasadena on the radio and being immensely cheered at the outcome.

I could not have known it, but Michigan was about to enter the longest fallow period in its history. It would be another 14 years before it returned to the Rose Bowl, and losing seasons would become commonplace.

Michigan State, at the exact same time, was turning into a national power. Two years after I chose Michigan as the team of my heart, the Spartans won the national championship. In the very next season, their first in the Big Ten, they won the conference title and went to the Rose Bowl.

Many of my peers quickly became big Michigan State fans. But I had made my choice, and even at that tender age it seemed shallow to cast it aside so quickly. I felt I was a better person than that. The born-again MSU converts were like the kids who showed up at our softball games wearing Yankees caps. They never actually got beaten up, but they were despised as front-running geeks.

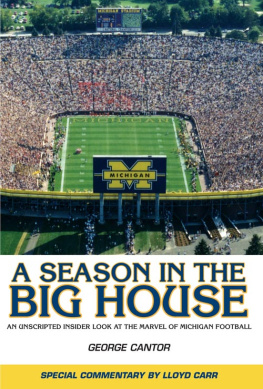

Still, it was hard. In 1955, for example, Michigan won its first six games and was ranked number one in the country. It was a magnificent crew, led by All-American ends Ron Kramer and Tom Maentz. Their pictures appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated . I went to my first game in The Big House that fall and watched them dismantle Army, 262.

Then they went down to Champaign and were simply corked by a nondescript Illinois team, 256. I was keeping score of this mess at home, and at one point in the fourth quarter simply hurled my notebook across the room in a rage and switched off the radio. It was a course of action I would come to repeat all too often.

Incidentally, Em Lindbeck, the Illinois quarterback who directed this disaster, became a baseball player. His only two games in the majors were with the Tigers. He batted once and failed to get a hit. It figures.

Michigan also lost its final game that year to Ohio State. This was during the very core of the era in which Woody Hayes had decided the forward pass was an unmanly fad that was not properly part of football. He simply rammed the ball down Michigans throat and dared them to stop him. They could not.

This is also the year I learned not to like Ohio State very much. If any fair correlation to the Yankees can be drawn, it is with that school. George Steinbrenner is a graduate of Ohio State and an avid Buckeyes fan. Michigan supporters are absolutely convinced that he signed Drew Henson to a whopping baseball contract for the sole purpose of leaving the team without an experienced quarterback.

There is, however, a slight basis for the comparison to the Yankees. They had a losing season in 1925, when Babe Ruth went down with a bellyache that was later revealed to be venereal disease. They didnt have another one until 196539 years in a row without a losing record. The Wolverines last had a losing season in 1967. Going into 2006, that makes 38 years in a row.

Very impressive. But now we get to the anguish part.

While the Yankees won 19 championships during their streak, Michigan has won only one. In their final game of the season during that time, either against OSU or in a bowl game, their mark is 14231.

So you see, those who speak of the Yankees are simply clueless. Its more like being an Atlanta Braves fan. You win every year except when it comes to the games that matter.

Bo Schembechler pointed out, however, that not one of those end-of-the-season losses cost Michigan a national championship. Even though he went into the last game with a perfect record five straight times between 1970 and 1974, and then lost or tied it, the title would have gone elsewhere even if Michigan had won. Never were they ranked higher than third before any of these sad finales. In fact, the latest that a Schembechler team held the number-one spot was November 6, 1977, when they lost at Purdue, 1614, on a missed field goal at the gun.

I can still hear Bob Ufers mournful cry into the mike. No good, he muttered. No good. No good.

Since Schembechlers retirement, even accounting for the 1997 championship year, Michigan has been ranked first for a grand total of only four weeks.

It isnt as if they always fall short. Its more a case ofyou knowthings happening. Bad things.

So while some may call Michigan fans arrogant asses, we know in our hearts, as George Will once wrote about following the Chicago Cubs, that man is not born to pleasure.

My intention in writing this book was to get at the mystique of being a Michigan fan. There are so damn many of us, and we are so disposed to hope for the best and expect the worst.

Predictions for the 2005 season were typically bubbly, and it appeared that it could be a year worth remembering.

That prediction turned out to be correct, but for all the wrong reasons. No one anticipated a season that resembled a tightrope walker with the DTs. At times it seemed it would all plunge to ruin, and at others it appeared that the safety of the far side was only a shaky step away.

Neither turned out to be true. Absolutely stirring victories were outweighed by absolutely crushing losses. It sometimes seemed as if we were witnessing the end of an era of Michigan dominance and the start of a slow descent into the ordinary. Either that or it was the most god-awful streak of bad luck ever to hit a football team.

Next page