The Reporter Who Knew Too Much

The Reporter Who Knew Too Much

Harrison Salisbury and

the New York Times

Donald E. Davis and Eugene P. Trani

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2012 by Donald E. Davis and Eugene P. Trani

Goodbye to Harrison Salisbury, Who Introduced Me to Russia, by Gwendolyn Brooks, reprinted by consent of Brooks Permissions.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Davis, Donald E., 1936

The reporter who knew too much : Harrison Salisbury and The New York Times / Donald E. Davis and Eugene P. Trani.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-1949-6 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-4422-1951-9 (electronic)

1. Salisbury, Harrison E. (Harrison Evans), 1908-1993. 2. JournalistsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Foreign correspondentsUnited StatesBiography. 4. New York times. I. Trani, Eugene P. II. Title.

PN4874.S266D38 2012

070.92dc23 [B]

2012026756

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For our mentor, Professor Robert H. Ferrell

teacher, scholar, role model.

Journeyman Journalist

Condolences flooded Charlotte Salisburys mailbox after her husbands death on July 5, 1993, at the age of eighty-four. They had first met in 1955, but it was not until 1964 when she was fifty that they marrieda second for him and a third for her. He referred to her as his love and comrade. She called him Harry and had always realized that Harrison was important to American reporting and needed space. David Levines whimsical pen-and-ink sketch of Harrison for the New York Review of Books in 1967 was a good sign that Harrison was no ordinary journalist. Levine pictured him as lean and mustachioed, with fingers outstretched to his Remington Standard typewriter. Homages to the writer portrayed him as a mighty journalist of the daily news, an editor of the New York Times, a winner of Pulitzer Prizes, a founder of the op-ed page, a Russia and China expert, and an author of twenty-nine books.

Charlotte, Harrisons wife of almost thirty years, contrasted Levines caricature with her favorite picture of him, the one she kept on her end table, the one with a soft smile and warmly glowing eyes. That was her Harry, the one she remembered best.

Colleagues and contemporaries were exuberant in their praises and saddened by a heartfelt loss. New York Times columnist Russell Baker summed up Harrisons lifetime of reporting: The work was so important that a grown man could be proud of doing it well. Harrisons protg, David Halberstam, thought of Harrison and Charlotte as role models and referred to him as an American original. Halberstams friend and fellow journalist David Remnick wrote, I am so terribly sorry that Harrison is gone. I can only tell you that as a journalist and as a man he was a great hero to me, an absolute example of what it was, and is, to report honestly, to write honestly, and to live honestly. Hedrick Smith, like Remnick part of the generation after Harrison on the Moscow beat, told Charlotte, He was always going to the heart of the matter, whether in Hanoi or Moscow or Birmingham or 43rd Street. Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr., publisher of the New York Times, summed up everyones thoughts: I would often subject my actions or decisions to a simple test: What would Harrison think?

Salisburys friends echoed the journalists tributes. Helen Frankenthaler, the American abstract expressionist painter, said of him, What an elegant and hearty man he was! She continued, His generosity of spirit, his humor, his patience[; he] was never too busy to pause for consideration. John V. Lindsay, former mayor of New York City, echoed others in expressing the terrible shock of Harrisons passing. The diplomat George F. Kennan wrote Charlotte, I think you know how much both his life and his work meant to me. His contribution to Americas understanding of Russia and China was unique. Former President Richard Nixon told Charlotte that Harrison was a fine reporter, a fair critic, a good friend and always a gentleman. Gwendolyn Brooks, Americas poet laureate, concluded her condolences with an original poem, Goodbye to Harrison Salisbury, Who Introduced Me to Russia:

A colon is tense.

A semi-colon relaxes a little.

Such facts he knew.

He knew also how to enjoy, how to nourish, when and how to review, how to edit

and tally.

And finally he was a skilled hand at the wheel of coordination.

The world will miss the quick-stepping body that served itself and the world, wisely.

The world will miss the supporting spirit, the furioso, the andantes.

Bravo.

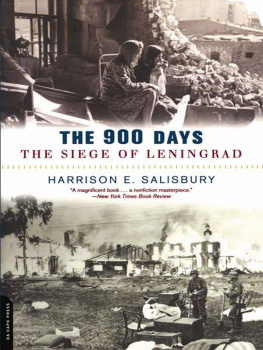

Eric Paces obituary in the New York Times, July 7, 1993, outlined the arc of Salisburys career. Pace cited his leading assignments in Chicago, Washington, DC, New York City, London, and Moscow. Squeezed among these were Birmingham, Alabamawith its resulting libel suithis editorship of national news coverage at the Times during Kennedys assassination; Hanoi; the Balkans; and, then, China and its orbit. Pace quoted Turner Catledge, former New York Times editor: Mr. Salisbury was versatile, a journalistic one-man band. The Times op-ed page was the start of its kind, and Harrison was its first full-time editor.

Two collections of testimonials appeared, one in the Proceedings ofthe American Philosophical Society and the other in the Nieman Reports of Harvard University. John B. Oakes, once editor of the New York Times editorial page, wrote that Harrison was much more than a celebrated journalist, historian, political analyst, editor, author, or correspondent: Salisbury had become by the time of his death widely recognized as one of Americas most versatile men of letters. Yet, he continued, Harrison was always a reporter. One morning in late December of 1966, readers of the Times were startled to see on the front page a dispatch, bylined Harrison Salisbury and datelined Hanoi. He had personally experienced B-52 bombings from a makeshift shelter in the capital. As president of the American Academy, the Institute of Arts and Letters, and the Authors League, he had focused his attentions on freedom of thought and the press. At age eighty, he was in Beijing working on a TV documentary when the bloody massacre at Tiananmen Square took place beneath his window. Result: Tiananmen Diary: Thirteen Days in June, published soon after the riots. Age barely slowed his output. His book The New Emperors came out in 1992, and his last essays in 1993, under the title Heroes of My Time.

Playwright Arthur Miller wrote of Harrison that he had a particular sense for finding the power nerve of an event, by which he meant, the spine of power relations which the event cuts across. Miller agreed with Oakes: Fundamentally, he was a reporter down to the end, but one with an awesome moral courage. He really knew no favorites when it came to telling the facts. Of Harrisons books, Miller cited at least two of lasting permanence:

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.