William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2022

Copyright Anna Keay 2022

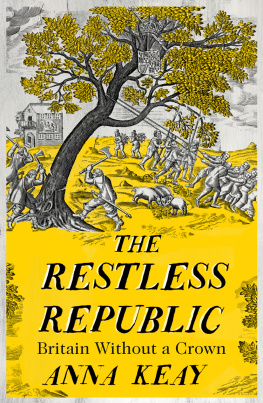

Cover design by Jo Thomson

Cover image: Felling the Royal; Oake of Brittayne (1649) Look and Learn / Peter Jackson Collection / Bridgeman Images

Anna Keay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

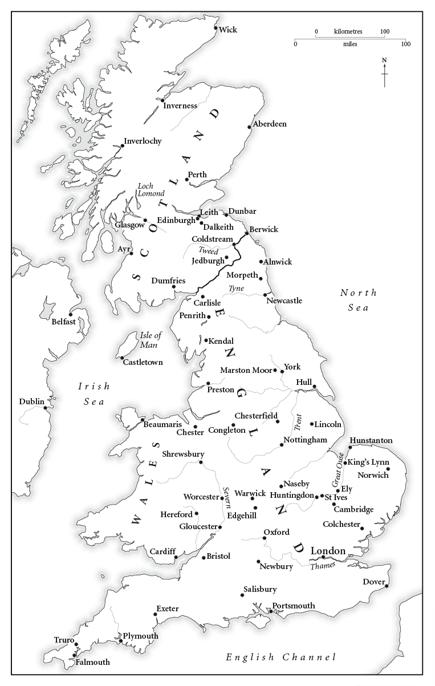

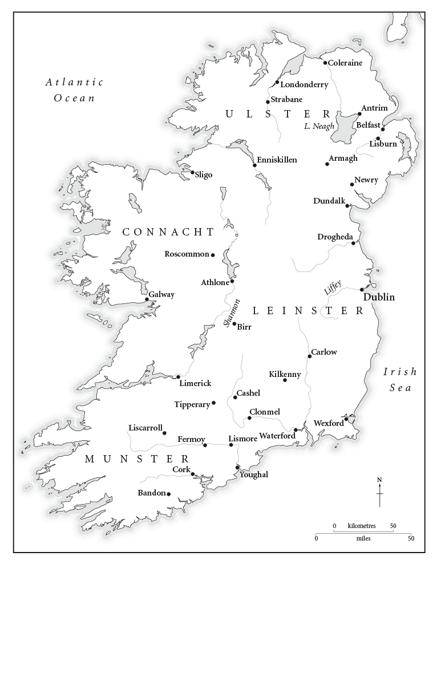

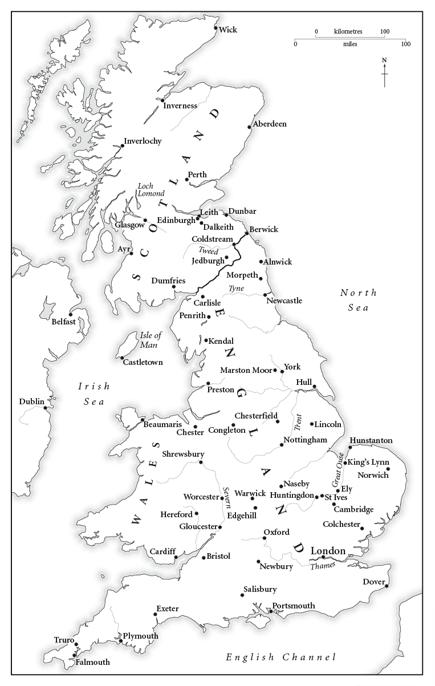

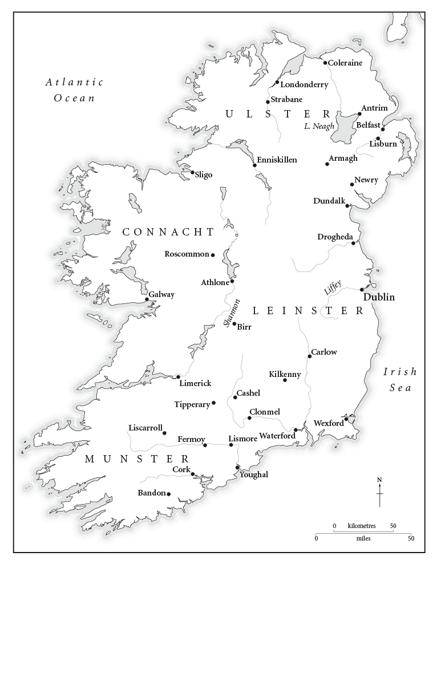

Maps, timeline and family trees by Martin Brown

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008282028

Ebook Edition March 2022 ISBN: 9780008282042

Version: 2022-02-07

FOR MAUD AND ARTHUR

This book was born of ignorance. Studies of the seventeenth century tend to deal either with some aspect of the kingdoms of the Stuart monarchy or with the world of the civil wars and the Revolution. There are lots of good reasons for dividing an entire century into manageable chunks, but it was not, of course, how it was. Those who walked the streets of Lincoln or London, shared a bottle of wine in the inns of Exeter or Edinburgh, in the 1630s often did so still in the 1650s and 1670s. Their dress and the style of their hair might have changed, and age would have weathered their skin and blurred their sight, but this was nothing to how the environment around them had shifted over that time. Few, if any, other generations of British people can have experienced such a period of national political and social change. Many of those I knew from both the earlier and later seventeenth century lived through these republican years and I wanted to know more of what they had experienced. Very few people tuck neatly into one historical age or another, or live only in the years with which they are most closely associated. Samuel Pepys and Christopher Wren, quintessential figures of the age of Charles II, were respectively a naval secretary and a pioneering mathematician during the 1650s. Oliver Cromwells daughter, Mary, and her husband Lord Fauconberg, whose boisterous wedding party Oliver himself had hosted, were popular figures at the late Stuart courts; the Earl was ambassador to Venice, a friend of the Duke of Monmouth and, later, a prominent supporter of the Glorious Revolution. Well into the reign of Queen Anne the residents of Cheshunt in Hertfordshire would see an elderly man out riding with his dogs, or sketching landscapes, who was none other than Richard Cromwell, one-time Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland.

This book attempts to inhabit Britain in the only period in its history when it was a republic and to try, by seeking to stand at the shoulder of a number of contemporaries, to understand what it was like and why. It is not a book about the civil war, which was largely over by the time it begins. But it is a book about life in a post-war land scarred by conflict and its monumental cost human, material and financial. The nine men and women taken as protagonists are not representative of British society the sources make this impossible but they do represent different experiences. Some, such as John Bradshaw, President of the first Commonwealth Council of State, stood at the centre of events, others, the young visionary Anna Trapnel or the Norfolk gentlewoman Alice LEstrange, at the periphery. Some, most notably Oliver Cromwell, are household names, others, such as the irrepressible newspaperman Marchamont Nedham, are unknown to all but academics. Through the surviving primary sources I have tried to piece together a picture of what their lives were in these years and to do so in a way which also tells the story of the age. The men and women of the 1650s were not two-dimensional woodcuts or joyless caricatures but real people, with friends and enemies, anxieties and aspirations, desires and disappointments like any person alive today. My hope is that through them the age in which they lived which was at times as unfamiliar to them as it is to us today might become more real and make more sense to we who, after all, walk in their footsteps still.

There is a risk in writing about a decade sometimes called the Interregnum that it becomes defined in the negative. Given our knowledge of what came next, it is easy to imagine that the return of the monarchy, the House of Lords and the episcopacy was inevitable and that these years were always destined to be a historical blind alley. This is not my contention. The 1650s was a time of extraordinarily ambitious political, social, economic and intellectual innovation, and it was not a foregone conclusion that the British republic would fail. But it was also a time about which a characterisation in the negative, Britain without a Crown, is relevant. The decade was defined to a significant degree by what was being rejected. Indeed part of the reason for the fall of the republic was that its protagonists agreed far more on what they did not want than what they sought in its place. Furthermore one of the republic of Britains enduring legacies has been as a historical cautionary tale, a ghoul summoned up at times of turmoil to deter later generations from a course of radicalism. That the United Kingdom remains a monarchy to this day is due in no small part to the events and experiences described in this book.

While the book has Britain in its title, it is fully acknowledged that Britain here rather as was the case with the first British parliaments of 16569 is weighted towards England.

Dates follow the Old Style Julian Calendar used in England at the time, but with the new year taken as starting on 1 January. Quotations are given with the original spelling unless otherwise stated. Readers who find this hard to understand are encouraged to say the words aloud.

One

There could hardly have been a more apposite place in which to make the decision to execute Charles I than the Painted Chamber at Westminster. When the clouds broke during the numerous morning meetings here in January 1649, elongated lancets of sunlight streamed through the tall Gothic windows onto the matted floor and down the table where the men who brought the King to trial gathered. Created for Henry III four centuries before, this was once the Great Chamber of the medieval Palace of Westminster. Outside a terrace of royal gardens lay between the massive stone building and the wide River Thames, while inside the high walls had once been painted with the vivid royal and biblical scenes to which it owed its name. This was the chamber where medieval kings had slept and dined, and where they had taken counsel. The building works had been completed just in time for the meeting of Henry IIIs Great Council of January 1237. Here the Plantagenet king had secured agreement to the taxes he wished to levy by promising various concessions to his subjects. During this, the first gathering in English history to be called a parliament, he had pledged to reissue the famous undertaking which his father King John had signed, and then repudiated, Magna Carta. With it was established the principle that everybody, even the King, was subject to the law.