Also by Sarah LeFanu

S is for Samora: A Lexical Biography of Samora Machel and the Mozambican Dream

Rose Macaulay: A Biography

Dreaming of Rose: A Biographers Journal

The Lille Diaries (with Jenny Newman and Michle Roberts)

In the Chinks of the World Machine: Feminism and Science Fiction

Radio dramas

Thin Woman in a Morris Minor

Death Bredon

As editor

Colours of a New Day: Writing for South Africa (with Stephen Hayward)

Obsession (with Stephen Hayward)

God (with Stephen Hayward)

Sex, Drugs, RocknRoll: Stories to End the Century

How Maxine Learned to Love her Legs and other Tales of Growing Up

Letters from Home

Despatches from the Frontiers of the Female Mind (with Jen Green)

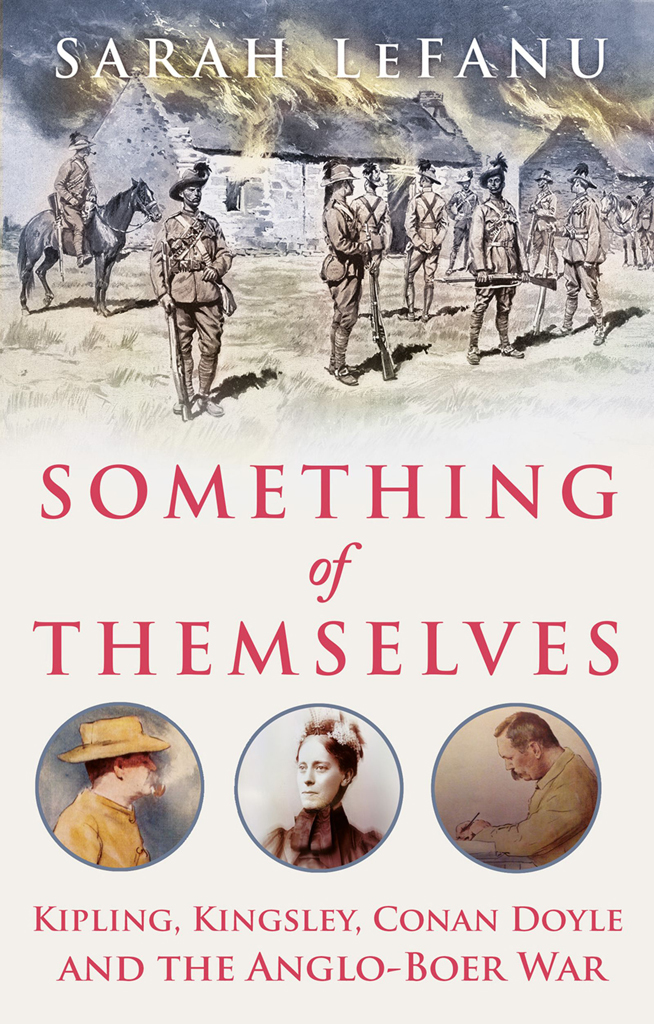

SOMETHING OF THEMSELVES

SARAH LEFANU

Something of Themselves

Kipling, Kingsley, Conan Doyle

and the Anglo-Boer War

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Sarah LeFanu, 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 9780197501443 (print)

ISBN 9780197536018 (updf)

ISBN 9780197536070 (epub)

Names: Sarah LeFanu

Title: Something of Themselves

in mem. Stephen Hayward 19542015, friend and comrade

CONTENTS

National Portrait Gallery, London.

National Trust Images/ John Hammond.

Image courtesy of the Kipling Society.

Image courtesy of Rice-Aron Library, Marlboro College, Rudyard Kipling Collection, and the Landmark Trust, USA.

Image courtesy of Durbach/ Kipling Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.

Image courtesy of Durbach/ Kipling Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.

Image courtesy of the Council of the National Army Museum, London.

Image courtesy of Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Image courtesy of Cambridge University Library: Royal Commonwealth Society Library, Derek Holt West African photographs (Y3043PP).

Image courtesy of The University of Liverpool Library (D674/2/2/1).

Image courtesy of David Erickson, Simons Town Historical Society.

Image courtesy of David Erickson, Simons Town Historical Society.

Image courtesy of Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford (1900.39.70).

Image courtesy of Conan Doyle Estate Ltd.

Image courtesy of Conan Doyle Estate Ltd.

Illustrated London News, 2 June 1900. Image courtesy of Doug Wrigglesworth.

Image courtesy of Ken Cooper.

Image courtesy of Conan Doyle Estate Ltd.

Image courtesy of Conan Doyle Estate Ltd.

Ozy.com, public domain.

Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Image courtesy of King Edwards Foundation Archive.

Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

National Portrait Gallery, London.

Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Image courtesy of the Council of the National Army Museum, London.

Black & White, 26 May 1900. Image courtesy of Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives.

The Illustrated Police News, 21 July 1900. Image courtesy of British Library Newspaper Archive and David Erickson, Simons Town Historical Society.

Image courtesy of University of Bristol Library, Special Collections.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright-holders and obtain permission to reproduce this material. Please do get in touch with any enquiries or information relating to an image or the rights-holders.

South Africa

During the first months of the twentieth century three British writersRudyard Kipling, Mary Kingsley, and Arthur Conan Doylesailed separately to South Africa to participate in the war that had broken out between Britain and the Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. War had been declared in October 1899; the British public had been assured that it would be over by Christmas. It was pointed out that the Boers, after all, had no proper army. No one believed that 30,000 farmersfor the Boers were farmers, not soldierscould stand up for long against what the anti-imperialist Olive Schreiner bitterly called the greatest empire upon earth, on which the sun never sets, with its five hundred million subjects.

By Christmas, however, British confidence was badly shaken. A string of unexpected military defeats had resulted in shockingly high casualty rates. On top of that, hundreds of British soldiers had been taken prisoner, an unheard-of humiliation. Inside the British territories of Natal and the Cape, the towns of Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking were under siege by Boer forces.

Rudyard Kipling had visited South Africa twice before, and was already on friendly terms with the big noises in British and colonial circles: with Sir Alfred Milner, high commissioner of the Cape Colony, and with the ambitious, eccentric, former prime minister Cecil Rhodes, who had been obliged to resign in 1896 for his involvement in the anti-Boer fiasco of the Jameson Raid. For Mary Kingsley and Arthur Conan Doyle, however, it was their first visit.

Mary Kingsley, traveller, ethnologist and campaigner for the rights of black Africans in Britains West African colonies, signed up with the War Office as a nurse; Arthur Conan Doyle, who ten years since had given up medicine for full-time writing, lifted his stethoscope out of its case and volunteered as a physician in one of the privately funded field hospitals being hastily organised; Rudyard Kiplings poem The Absent-Minded Beggar, published in the Daily Mail at the end of October, had raised over 250,000 for soldiers and their families. He set off for South Africa as propagandist-at-large and general morale-booster for the imperial troops.

When the war was eventually brought to a close, two-and-a-half years later, in May 1902, 22,000 British and colonial soldiers would have lost their lives, over half of whommore than 13,000would have died of disease, mainly typhoid.

The typhoid that devastated the British troops shaped the experiences of my three subjects. Conan Doyle had thought that he would be tending to the war wounded, but instead he found himself in Bloemfontein in the midst of deathand death in its vilest, filthiest form. Also in Bloemfontein, where he was acting as co-editor of a local paper commandeered for the British army, Kipling watched the hasty burials of corpses wrapped in brown army blankets for want of enough regimental flags to go round: Bloemingtyphoidtein a soldier calls it in Kiplings poem The Parting of the Columns. In Simons Town on the Cape Peninsula, 600 miles south-west of Bloemfontein, Mary Kingsley was nursing typhoid-stricken Boer POWs. Both Conan Doyle and Kipling were safely home in England by the summer of 1900, but Mary Kingsley never returned. She caught typhoid and died of its complications. On 4 June 1900 she was buried at sea, as she had requested in her final hours.