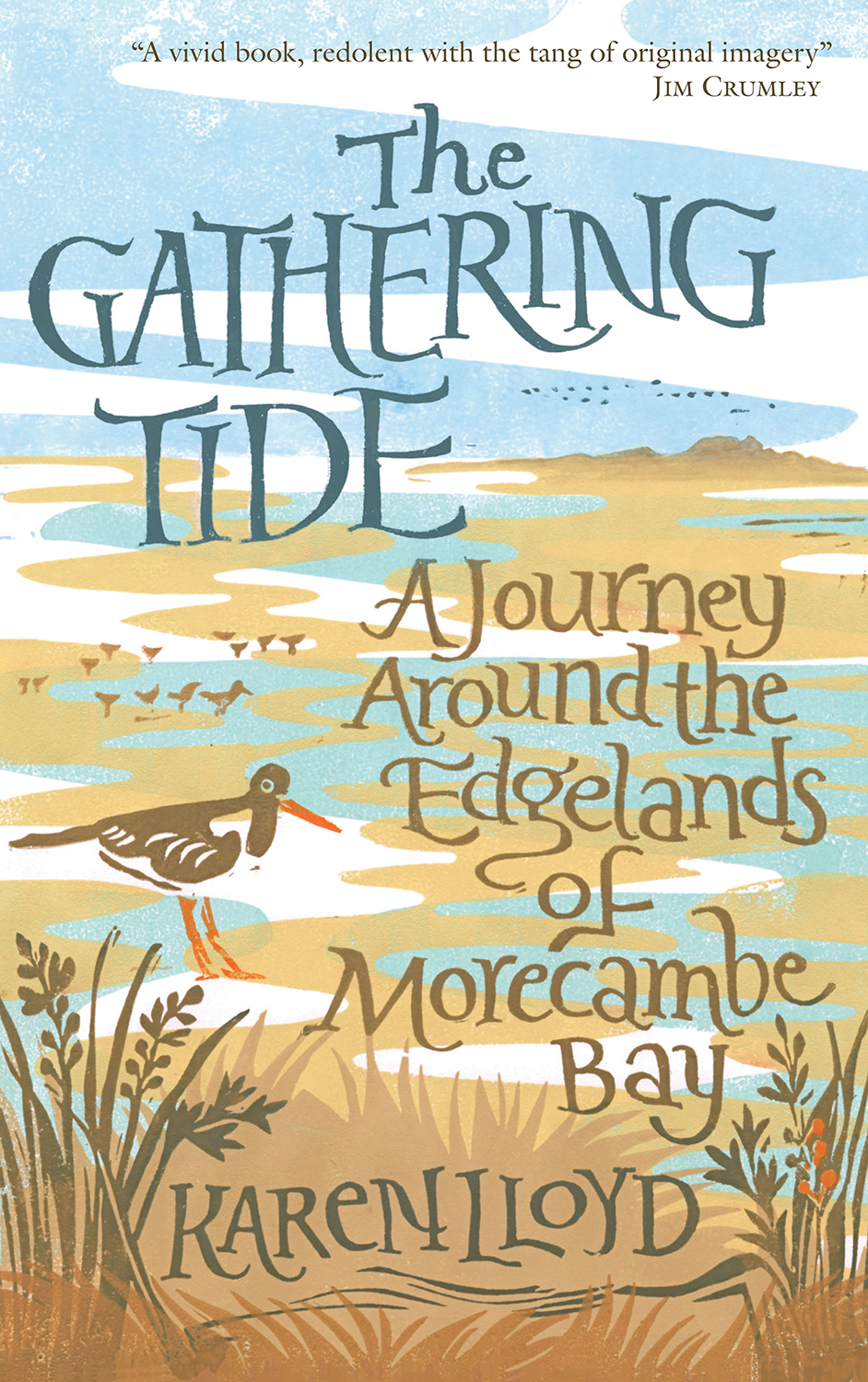

Praise for The Gathering Tide

Evocative, muscular an artists eye for colour and a dynamic way with verbs provide energy. Though bright and sensitive there is also an no-nonsense earthy quality to the writing pleasingly Cumbrian! Kathleen Jamie

This poetic book is a map, a layered account of Morecambe Bay, its birds, rivers, names, bones, weathers, ghosts, tides and lives, its dangerous beauty, its tragedies. Karen Lloyd keeps company with the living and the dead, neolithic burials, the grave of a black slave boy, the Chinese cockle-pickers lost to the rising tide in 2004. In mapping a place and sharing its beauty with her reader, she arrives at her own sense of belonging. Gillian Clarke, poet

A vivid book with a landscape at its heart, redolent with the tang of original imagery. The hallmarks of good nature writing are in place a seeing eye, that willingness to watch alone that deepens the bond between nature and writer, and the capacity for celebrating what Hazlitt called the involuntary impression of things upon the mind Jim Crumley, nature writer

Slides effortlessly from the environment to history, to stories of other people, to personal anecdote [It] succeeds magnificently. Robin Lloyd-Jones , author of The Sunlit Summit

The Gathering Tide

A Journey around

the EdgeLands of

Morecambe Bay

Karen Lloyd

Contents

For Steve, Callum and Fergus

the three men at home

I look; morning to night

I am never done with looking.

Mary Oliver

Introduction

In 2004, on a freezing cold February night, 24 Chinese men and women were cut off by a fast-moving incoming tide and lost their lives; suddenly, horribly, Morecambe Bay was firmly on the global map. Images of the bay and stories of its inherent dangers were beamed across the world, catapulted via predictably ghoulish media stories into the sitting rooms of people who had never heard of the place. Through this single incident, the wider world knew what those of us who grow up near the bay have known for our entire lives: it is a place of inherent danger. In certain locations, even to venture more than a metre or two from the shore can lead to difficulties: the rapid ebb and flow of the tides, the shifting sands, the quicksands and the channels that regularly alter their course are understood by just a small and shrinking breed of men who fish out on the bay, or who carry on the ancient tradition of guiding people across the sands. There is an irony then, that the most recognised part of Morecambe Bay is in reality its least knowable.

When I did venture out far out into the middle of the bay with Cedric Robinson, the Queens Guide to the Sands I found it a landscape that was at once unnerving, unsettling and incredible. On a day with high cumulus clouds and infinite blue space above reflected in the skin of water left behind by the tide, and in the shallows of the River Kent, I saw a strange wilderness of unfamiliar, beguiling beauty.

But what of the bays edgelands?

Almost 60 miles of coastline circumnavigate Morecambe Bay. Although I was aware of many places on the perimeter, through the osmosis of having lived for years close to the bay, there were others I had neither visited nor knew of. Collectively these had long been eclipsed not only by the footprint, or idea of the bay itself, but also by another adjacent star-turn the Lake District. And even though I loved the mountains and valleys, I knew that there were places around the bay that possessed their own understated qualities. It seemed high time their story was told too. The collective feelings of despondency and responsibility that many local people felt following the disaster of 2004 rumbled on for years. Over time though, I began to build a picture of how else the bay might be seen.

So I planned a neat end-to-end affair, a sequential set of walks around the edgelands of the bay bookended by the beginnings of one New Year and the last of the old. On an early January morning I set out to walk to Sunderland Point, where the River Lune flows out to meet the Irish Sea. Some maps show Knott End and the broad outfall of the River Wyre as the southern extremity of the bay, but I drew my own border at the Lune.

Mostly I walked alone, though on a small number of days I took along a companion; once a friend from school days I hadnt seen for 30 years. Both of us found more than wed anticipated that day. Memories came flooding back as we walked. Wed stop to look, to reconnoitre the place as its ecology had shifted significantly in the intervening years. Wed both lost close family; lives had moved on.

At times on the journey around the bay that reconnoitring of the past became a job that needed to be done in its own right. So in a sense I found myself making an unwitting pilgrimage through the past as well as the present. Memories, and the feelings that they invoke, are at their strongest, possessing the deepest resonance, when they come unbidden, unlooked for. On they came, washed in by the bay, through the landscape, the light, through encounter, and they even came delivered through the portals of ancient sea charts and the contours of contemporary maps. On one significant day, they flew in on the small, white wings of a particular bird at the liminal space between the sea and the land.

Of course, the planned, tidy, year-long journey didnt happen. During the first year of writing I was spending large amounts of time away from home. Life got in the way. But the walking and the collecting of stories continued. Alongside the days spent observing landscape, were meetings with people whose deep understanding opened up new seams of knowledge for me. I found evidence of ancient roadways buried underneath the peat, of caves where wolves and lynx once fed, and a ghost in the grass in a country churchyard beside the sea. Like life itself, some of the best moments I spent observing and researching revealed incidents that were not, and could not have been planned.

Karen Lloyd

August 2015

One

Sunderland Point

I stood at the edge of the bay, looking out to where cloud shadows fell onto the immeasurable sands, colouring them deep Prussian blue and red ochre. The whole saltmarsh was silent, the kind of silence that hums in the ears, and it spread over the singing blue of a frozen morning. Then a redshank materialised from a channel close by and unfurled itself skywards, casting its singular ticking call into the sky. My cover was blown and the whole marsh knew I was there.

Over the fells of Furness and further, beyond the Duddon shores, Black Combe had turned other-worldly, snow-capped, like Mount Fuji transplanted. Id driven through the brightening of an early January morning, the lanes funnelling into a narrow single track, passing caravan sites and low-lying winter fields where flocks of goldfinches sparked out of the hedgerows. There was a sense of getting closer to the coast; the way the light shifted, paling as it fell towards a seaborne horizon.

Then a place to park by the edge of the bay and, at the roads end, a few houses and gardens sheltered by trees. Rooks were high up in the motionless branches; feathers ruffling, wings restless. I pulled on boots and gloves, and gathered together the bits Id need binoculars, notebook and pen and stuffed them into pockets before setting out to walk in extraordinary light. A pair of curlew flew up. As though choreographed, more appeared, surfacing and launching forward in sequence, out from the sea-pools and channels that threaded curving ribbons of water towards the bay, a good half-mile distant over the marsh. Arcing above me, they surged seaward, making the sky brimful with their bittersweet calls. This, of all the cadences of the natural world, fills me with the fizz of wild electricity. Oystercatchers evolved out of the distance, the flash and message of them, the sound building to a crescendo, insistent. Over the shoreline dunlin massed, flowing and peep-peep ing through the breath-cold morning sky. Underneath all this, the persistent chatter of turnstones.