All rights reserved under all applicable International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

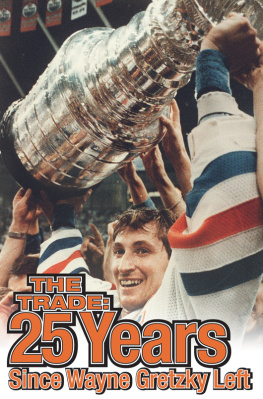

By Rick McConnell

This is a story about a hockey trade.

Except it is more than that, or not only that. And, at times, not that at all.

While this is essentially a story about the greatest hockey player who ever lived and the biggest and most shocking hockey trade ever made, it is also a story that touches on chaos theory and para-social interactions and Rottenbergs Invariance Principal, on Albert Einstein and be-bop music, and on important lessons taken from John Wayne movies.

It is a story at once Shakespearean in scope, with larger-than-life villains and heroes, yet a story that can seem as simple as a fairy tale, though perhaps with a larger metaphor lurking just beyond the grasp of our understanding.

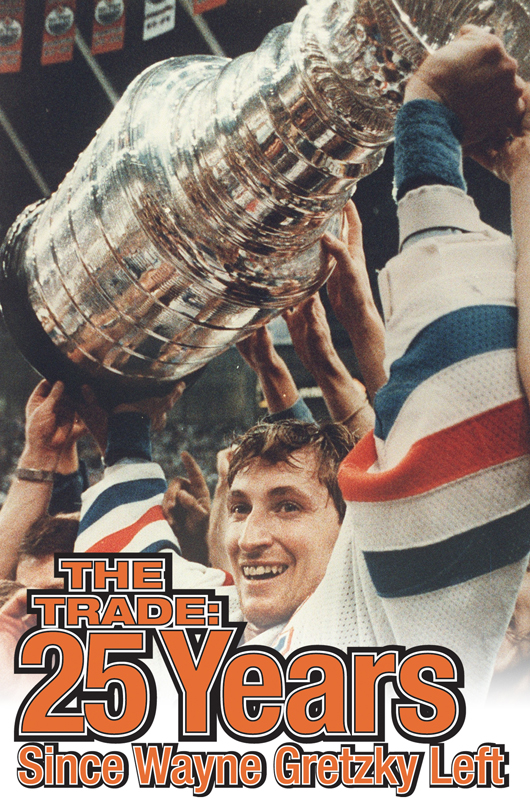

It is a story that tries to explain the importance of what happened on Aug. 9, 1988, while touching on the things that led up to it, the things that have happened since, and what it felt like during those nine extraordinary years when hockey fans in this city witnessed the birth and growth of a star who now seems as much myth as memory.

To understand the impact and importance of the trade, it seems necessary to first come to terms with who Wayne Gretzky was, where he came from, and how he transformed the way hockey is played and perceived, how he forever altered the sport and the marketplace within which it exists.

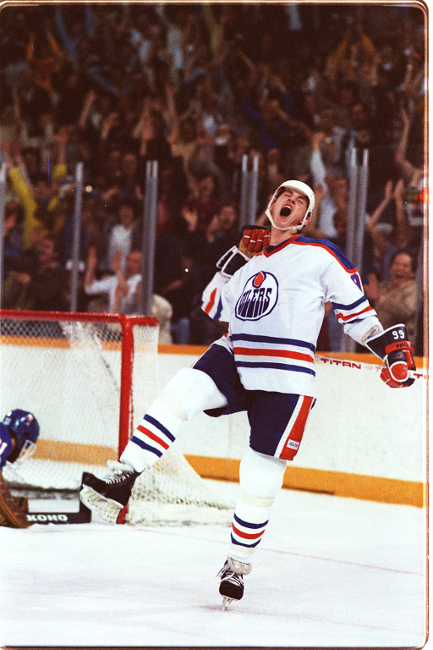

He has been called the Einstein of hockey and the Mozart of hockey, and those are interesting phrases but are merely comparisons, not explanations. The simple fact is, genius cannot be explained, though you might spend days searching for ways to try to do precisely that.

Lets begin with the fact that he was the Great Gretzky long before he set foot in Edmonton. The first major newspaper article about him, written by a student reporter named John Iaboni, ran in the Toronto Telegram on Oct. 28, 1971. Iaboni, who produced a weekly minor hockey page for the soon-to-be defunct Telegram, had been told there was a 10-year-old in Brantford who was better than Bobby Orr. He resisted at first, then finally, reluctantly, made the trip to the North Park Arena. There, he discovered the first makings of a myth.

Theres a Little No. 9 in this town who has ambitions of replacing the recently retired Big No. 9 of the Detroit Red Wings, Gordie Howe, Iaboni wrote. Now in his fifth novice A season with Brantfords Nadrofsky Steelers, the 4-foot-10, 70-pound defenceman-winger-centre has notched 369 goals thus far. (His season total, in 85 games: 378).

On that trip, Iaboni was asked by an eight-year-old boy if he was a newspaper reporter.

Are you going to write a book on Wayne Gretzky? Hes good, you know.

Iaboni never wrote that book. But many have been written since.

From there, the myth began to spread. Soon, a whole hockey-mad country would begin to internalize the story as part of the national fabric, and thousands of Canadians would know that Wayne Gretzky was the oldest of five children born to Walter and Phyllis Gretzky; that Walter, who worked for Bell Canada, flooded the back yard every winter and put up floodlights and set up nets so that his preternaturally talented oldest son could play the game they both loved.

In March 1972, thousands of miles from Brantford, Journal readers may have seen a small sports item about a novice tournament in Brampton, Ont., where an 11-year-old named Gretzky scored nine goals and two assists to lead his team to a 12-2 victory. He was already a sensation.

They stared lining up at 6 p.m. to get into the arena to see him play, the tournament director told the Canadian Press.

During a Quebec tournament when Gretzky was 12, the big-eared lad was besieged by radio and newspaper reporters in the dressing room. People in the crowd, it was said, stole his sticks right out of the players bench to keep as souvenirs.

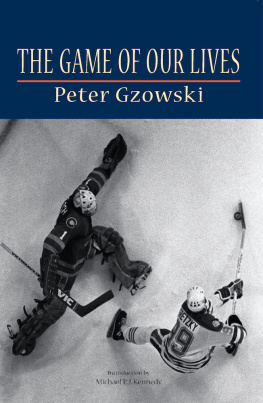

Peter Gzowski had the 13-year-old sensation on his CBC Radio program This Country in the Morning the following March. His interview subject shyly answered questions in the high, raspy voice of a boy just becoming a teenager.

Asked about his accomplishments, the kid rattled off scoring stats, one goal in his first year, 27 in the second, 104 in the third year, as an eight-year-old.

His coach, Ron St. Amand, sat beside him and talked about the scouts who were already attending Peewee games.

They probably heard a lot about Wayne and came to just see whether he was as good ... as theyd heard, he said.

He was.

Near the end of the interview, Gzowski asked the boy to speculate about how much money he might make if he turned pro by age 18. The teenager didnt want to answer.

Would you believe a million dollars? the host asked.

No, not really.

Skip ahead four years, the prodigy growing bigger (but not much) and better all the time, past two seasons playing midget in Toronto, into his one and only full season with the Junior A Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds of the Ontario Hockey Association.

By then, everyone was watching. Sports Illustrated sent a writer to Ontario in January 1978 to bring back the story.

If Wayne Gretzky were never to play another hockey game, E.M. Swift wrote in a feature article the next month, thousands of Canadian kids would remember him into their dotage.

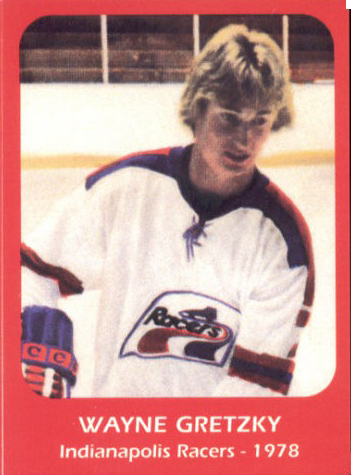

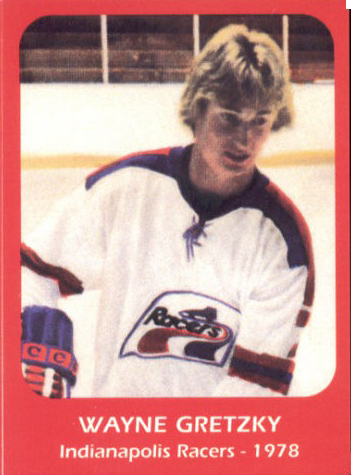

Enter Nelson Skalbania, owner of the Indianapolis Racers in the struggling World Hockey Association, which had started in 1972 as competition for the NHL, luring away some stars with big contracts. On Sunday, June 11, 1978, Skalbania landed his private jet at Edmontons municipal airport and met in a nearby hotel with two Journal hockey writers, who were given the scoop: he had just signed the 17-year-old to an $825,000 contract.