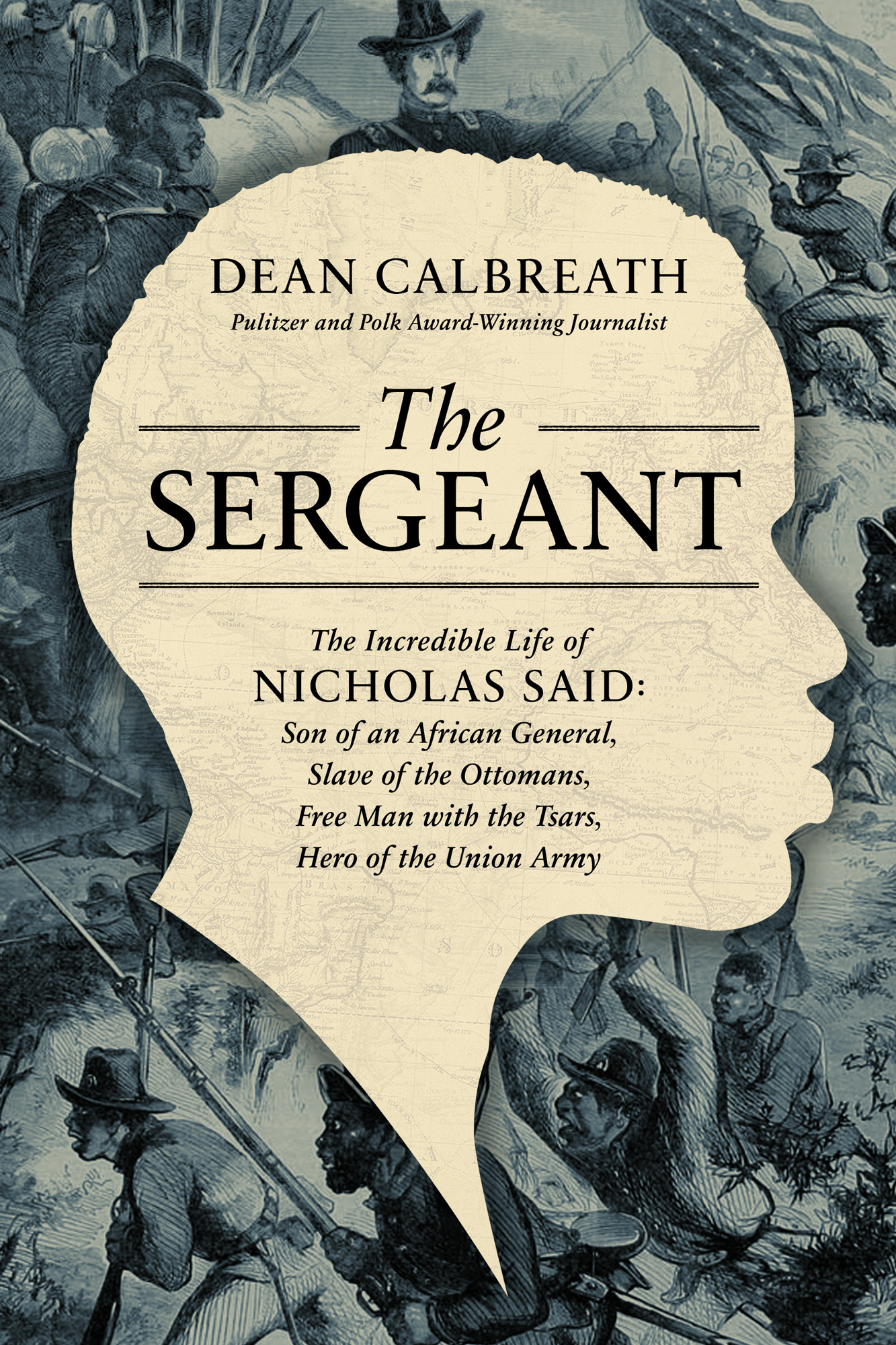

Dean Calbreath - The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army

Here you can read online Dean Calbreath - The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2023, publisher: Pegasus Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army

- Author:

- Publisher:Pegasus Books

- Genre:

- Year:2023

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In the late 1830s a young Black man was born into a world of wealth and privilege in the powerful, thousand-year-old African kingdom of Borno. But instead of becoming a respected general like his fearsome father (who was known as The Lion), Nicolas Saids fate was to fight a very different kind of battle.

At the age of thirteen, Said was kidnapped and sold into slavery, beginning an epic journey that would take him across Africa, Asia, Europe, and eventually the United States, where he would join one of the first African American regiments in the Union Army. Nicholas Said would then spend the rest of his life fighting for equality. Along the way, Said encountered such luminaries as Queen Victoria and Czar Nicholas I, fought Civil War battles that would turn the war for the North, established schools to educate newly freed Black children, and served as one of the first Black voting registrars.

In The Sergeant, Saids epic (and largely unknown) story is brought to light by globe-trotting, Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist Dean Calbreath in a meticulously researched and approachable biography. Through the lens of Saids continent-crossing life, Calbreath examines the parallels and differences in the ways slavery was practiced from a global and religious perspective, and he highlights how Saids experiences echo the discrimination, segregation, and violence that are still being reckoned with today.

There has never been a more voracious appetite for stories documenting the African American experience, and The Sergeants unique perspective of slavery from a global perspective will resonate with a wide audience.

Dean Calbreath: author's other books

Who wrote The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.