M Y LIFELONG FASCINATION with deer has had some unexpected consequences. One morning when we lived in Oxfordshire a farmer came on the telephone and said abruptly, Here youve got a big rifle, havent you?

I didnt know the man, but he was obviously in a state of some agitation, so I agreed cautiously Well, yes why?

I need someone to shoot a steer. The blasted things gone mad and its attacking its mates. People, as well.

OK, I said. Ill come down. Where are you?

The farm was only seven or eight miles away, down by the Thames, but such thick fog was lying on the Chilterns and in the river valley that it took me half an hour to nose my way through the lanes. Eventually I arrived at the agreed rendezvous, and found a posse of half a dozen locals waiting by a gate.

All right, I said, loading a couple of rounds into the .300 magnum. Where is it?

Over there. The farmer pointed vaguely into the fog, and we all started to walk across a grass field which, being down in the valley, was dead flat. Presently I made out a hedge running across our front, and on our side of it a single, hefty Hereford bullock pacing up and down as if preparing to put in a charge.

Thats him! said the farmer tensely. Why dont you shoot him?

Give it a minute, I said. Whats beyond the hedge?

Nothing.

Nothing?

Just the village.

The village! How far away are the houses?

About a hundred yards.

Jesus! What about in that direction? I pointed to the left.

Nothing that way.

At that moment I heard the unmistakable noise of a train rattling past in the fog.

What the hells that, then?

Oh, its only the embankment.

Listen, I said. If I miss, this bulletll go for two or three miles. We need to get organised.

After some manoeuvring, I got two men stationed as decoys, one on either side of the rogue animal, against the hedge. Turning back and forth, it could not make up its mind which to charge. By means of hand-signals I moved them inwards until each was about thirty yards from the bullock. I myself shifted to my right until I had it lined up in front of an enormous oak, with a trunk at least four feet wide. Even if I missed the crazed creature, I could hardly miss the tree. I then advanced until the bullock stopped pacing to right and left, and began to fancy me as a potential target. With everyone in position or out of the way, and the animal anchored by indecision, I lay down, took aim and put a bullet into its forehead. Down it went as if poleaxed, and within a couple of minutes it had been borne away hanging by the hocks from the fork lift of a tractor.

The farmer thanked me civilly enough, and I drove slowly home, pleased to have been of service. But the exercise had occcupied most of the morning, and I slightly hoped that in due course some small recompense might appear perhaps a pound or two of steak. For weeks, for months, nothing materialised, and in the pub I began making jokes about how Id shot only one steer during the season, but how challenging the assignment had been. Then suddenly there arrived a letter containing a note of thanks, together with a cheque for 25 a considerable sum, then, and far more than I had earned or deserved. I was left feeling guilty, for I feared that my stories had found their way back to the farmer and caused him to over-react.

E VERY MORNING IN term time when I was seven or eight my sister and I would bicycle off across country to catch the school bus, which picked us up at a point on a minor road about a mile from home. For some of the way we were on private estate tracks, but we preferred to take short cuts along woodland rides, even though, in winter, the paths were often so muddy that we had to dismount and push. When we reached the main road, we simply wheeled our bikes into the trunk of a gnarled old beech tree which had been hollowed out by fire. In those carefree days there was no question of any grownup escorting us, or of us locking up our battered steeds when we left them. Returning in the afternoon, we would pick them up and ride home.

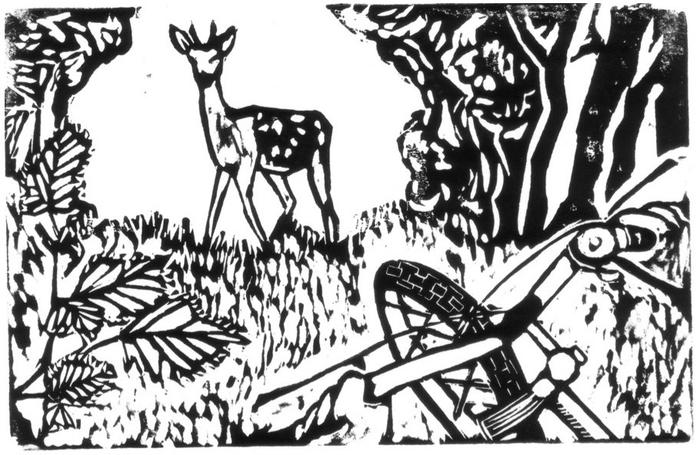

One summer day for some reason I came back on my own, and decided to cut through a wood which lay along the side of a hill. Much of it had once been coppiced hazel, but the bushes had been let go and grown tall, and at the far end they gave way to rough grass-land. As I emerged into the open patch, wheeling my bike, there stood a beautiful animal, broadside-on to me. Its chestnut-coloured coat, strongly marked with white spots, glowed in the sunlight. Legs and throat were white, and sharp little points of antlers protruded from the top of its head. Later I discovered that it must have been a fallow pricket a second-year buck of the menil variety, the kind with the strongest markings; but at the time all I knew was that it was a deer.

I was frightened, because the animal was so close, and so much bigger than me. Standing slightly higher up the bank, it looked even taller than it was. Transfixed, I froze and stared at it. For a few seconds the deer stared back at me. Then it wheeled round and bounded off, revealing a black stripe down the centre of its tail. Breathless with excitement, I leapt onto my bike and pedalled furiously for home, desperate to tell my mother what I had seen.

That was the start of a life-long involvement with deer and for me their magic lay partly in the fact that during the 1940s and 1950s the fallow were rare visitors to the Chiltern woods among which I grew up, so that I had few glimpses of them. Some had broken out of parks during the Second World War, when trees had fallen through walls or fences, and no men had been on hand to repair the damage. The escapers had spread out far and wide over the surrounding hills, and their descendants survived and gradually multiplied in the wild, mainly due to the huge programme of re-afforestation which took place after the war for the dense new plantations which sprang up everywhere provided them with ideal shelter.

Ignorance about deer was paramount in England at that time. There was no tradition of stalking, as in Germany, where elaborate rules had governed control of big game for centuries. British gamekeepers , foresters and farmers treated deer as vermin, occasionally killing them in shotgun drives and many went away wounded with a scatter of inadequate pellets lodged in their hide. Others, caught in snares or traps, died wretched, lingering deaths. A note in my game-book for 25 April 1950, when we were rabbiting, records: J. Cook shot at deer in the Heather, and it took a lot of shots to kill it an episode all the more deplorable if the animal was a doe and heavily pregnant, as it probably would have been at that time of year.

From some ancestor I had inherited a strong hunting gene. Neither of my parents had it, and to my knowledge my father the ultimate book-worm only once fired a shot at a live target. That was on a Boxing Day soon after the war. When a cock pheasant appeared, sitting on the garden fence about thirty yards from the house, the whole family urged him to have a go at it. Food was scarce, and there on top of the ivy-covered palisade sat the makings of a delicious meal, its brilliant plumage gleaming in the sun.

My father reluctantly got out his ancient .22 rifle, left over from Home Guard duties, but he could find only one bullet. While he settled himself on a chair in his bedroom, two of us gently eased the sash window up, and after taking prolonged aim, he fired.