Preface

The numbers stunned the industry.

The 46.6 rating meant that nearly half of all homes in America with TV sets were watching. Thats counting ones not using watching TV at the time too. And the 64 share meant that of all homes that did have their TVs on, nearly two-thirds of them were viewing this show.

The only shows that scored higher numbers than these were special events that aired on all the TV networks without commercials, like the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 and men walking on the moon in 1969. In contrast, this was just an entertainment program airing on one network on Jan. 15, 1970.

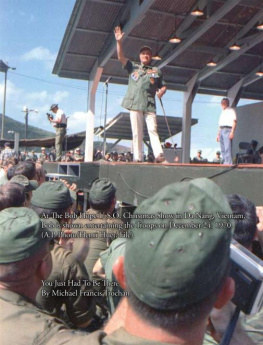

The show was Chrysler Presents The Bob Hope Christmas Special: Around the World with the USO, although most people including those in the industry referred to it as The Bob Hope Christmas Special. Its star had been a featured attraction for the NBC television network for twenty years and on NBC radio for more than ten years before that. And while Bob Hope certainly was well loved by the American public, no one had predicted this would be the highest-rated entertainment show in the mediums history up to that point.

One reason was competition. At the time, TV viewers could only choose between NBC, ABC and CBS in most markets (as well as noncommercial public television and a few independent stations in bigger markets, but the effects of those were negligible in the national ratings). On the night The Bob Hope Christmas Special aired, Bewitched on ABC was that networks top situation comedy, while The Jim Nabors Hour on CBS was a prime ratings contender as well, usually in the top thirty. This time slot looked like an imposing position for Bob to get a large audience.

Another was the shows content. This was the sixth annual visit Bob made to provide live entertainment via the United States Organizations, better known as the USO, to troops in the ongoing Vietnam War, which continued to be unpopular back home. There was every reason to suspect people were fatiguing of just the mention of the bloody conflict, which seemed to have no end in sight.

Then there was the guest list. Sure, Neil Armstrong was the first man on the moon just a few months earlier, but he had been interviewed and seen on TV previously. Teresa Graves was a regular on TVs number one series, Rowan and Martins Laugh-In, but not its star attraction. It had been at least three years since singer/actress Connie Stevens had done a movie and longer than that for a regular TV series or hit record, while foreign actress Romy Schneider was largely unknown to most Americans. As for the Piero Brothers and Miss World Eva Rueber-Staier, they were as obscure then as they are now.

Yet Bob who was executive producer as well as star of his show, a rarity among TV comedians had crafted a show designed to attract eyeballs in spite of its perceived obstacles. He made a special performance before President Richard Nixon in December 1969 to kick off his overseas tour, which gained the project free advance publicity, and designed the trek to go throughout the world to glamour spots like Berlin and Rome, not just in Vietnam. Bob also did his customary promotion of the show in advance of its airing on TV talk and news shows. And he was on a roll too, as seven of his nine specials during the 1969-1970 television season, including this one, ranked among the top eleven specials of the year. He clearly was tapping into Americas desire to laugh amid bad news with a familiar, comforting face.

For Bob, this ratings landmark was something of a bittersweet accomplishment. On the positive side, it confirmed his status as a leading entertainer as he was nearly in his seventies, an impressive accomplishment in the increasingly youth-obsessed world of show business. While most of his contemporaries were retired or scrambling for work, Bob was assured of his place in television.

It also showed that he remained popular with the younger generation of soldiers, even though many were the sons of men he had entertained first in World War II. Going to see Bob perform was a big deal to many of them, including future astronaut Guion Bluford. I was in Cameron Bay in Vietnam in 1966, 1967, he says. Bob did a Vietnam tour, he came on Cameron Bay there, and I saw him briefly in camp, but unfortunately I couldnt see his show because I was a fighter pilot on alert duty. I had to be ready to scramble F-4s if needed. I missed the program, which pissed me off, but thats life. He had no idea that he would later appear on one of Bobs specials as a guest in 1983.

The success also gave Bob favorable media coverage after months of unprecedented negative headlines for someone who consistently ranked as one of the most-loved entertainers in America. For one, reports came out that Bob had his regular stable of writers provide jokes for Vice President Spiro Agnew to bolster the latters combative public image, calling into question Bobs proclaimed apolitical approach to comedy.

He also felt so upset for what he thought was inaccurate reporting of the Vietnam War that he took the unprecedented step of opening the gated doors to his home in Toluca Lake, California, on Nov. 12, 1969, to hold a press conference. Bob called out his home networks division of NBC News in particular to claim its stories about racial disparities in treatment of combat soldiers was wrong. Such defenses about what was occurring in Vietnam led some to label Bob a warmonger.

There were some that say he was a hawk during the war, and I dont believe that, says Gene Perret, who wrote for Bob from the 1970s through 1990s. His feeling was These guys are over there, fighting there for our country. It was in support of people who were as much a victim as anyone else.

The ratings also were vindication for most of Hopes writers of the time, almost all of whom had been with him for at least a decade, usually more than that, and whose contributions Bob relied on extensively for the special. Lester White began writing for Hope when the latter was in vaudeville. When Bob went into radio full time in 1937, Norman Sullivan joined him and worked only on his monologues. Mort Lachman, who would direct the overseas Christmas specials as well as produce Bobs specials overall starting in 1964, started doing Bobs radio show in the 1940s.

Others joined Hope during the early 1950s on TV, including Lachmans writing partner Bill Larkin and British-born Charlie Lee, who wrote solo until paired in 1964 with occasional contributor turned regular writer Gig Henry. Lester Whites writing partner had been Johnny Rapp for at least fifteen years until 1968, when Lester worked a year with Larry Rhine and then Mel Tolkin effective the fall of 1969.

Tolkin described his activities for Bob to Tom Stempel in Storytellers to the Nation: A History of American Television Writing thusly: You work not only for his specials, you work for his gigs, his trips to Vietnam and Korea. You work on dinners, gigs in honor of somebody, charity gigs. Wherever he is, we get a poop sheet that we write jokes [from], whos on the dais, something about the man being honored, the occasion, areas for comedyand of course the poop about the places, Vietnam and Korea, the temperature, the animals around, what the soldiers eat, where they hang out.

Despite having such insights provided, the writers gag lines on the special did not always pan out. Bob found mixed reception at best to jokes about the new draft lottery system and the Paris peace talks. Clearly, the rank and file were sick of hearing about the progress of the war or the lack of it as much as being part of it.

In addition, Bob faced the toughest reception he ever encountered among usually friendly soldiers watching the performances before and during Christmas in 1969 (Bob and crew edited footage from several shows filmed along with visits with officials for use in the annual specials). The worst was in Lai Khe, where soldiers booed him heartily for saying President Nixon would bring them home soon and kept doing so as he brought out other performers on stage with him. It took Connie Stevens singing Silent Night to calm everyone down finally.