Contents

Guide

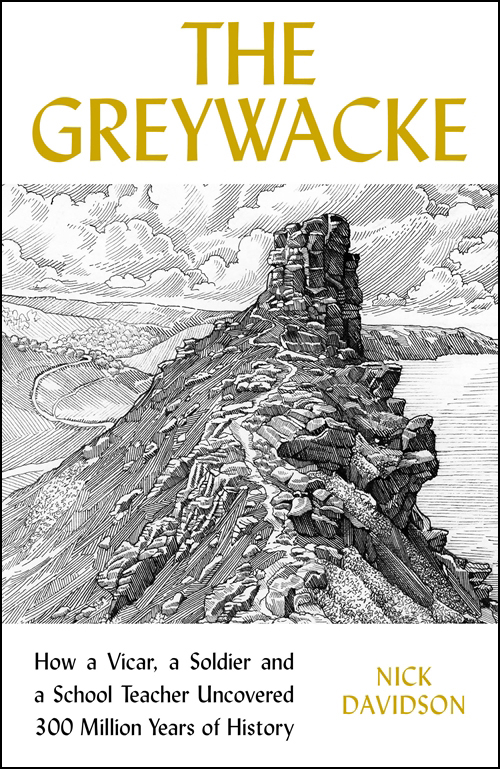

THE GREYWACKE

THE GREYWACKE

HOW A PRIEST, A SOLDIER AND A SCHOOL TEACHER UNCOVERED 300 MILLION YEARS OF HISTORY

NICK DAVIDSON

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Profile Books Ltd

29 Cloth Fair

London

EC1A 7JQ

www.profilebooks.co.uk

Copyright Nick Davidson, 2021

Lines from The Lymiad (p. ) Lyme Regis Museum

Lines from The Everlasting Mercy (p. ) The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of John Masefield

Original illustrations Andrey Kurochkin, 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781788163774

eISBN 9781782836261

For Leo, Felix, Emma and Zander who will one day, I hope, come to enjoy the rocks as much as I do

INTRODUCTION

Some years ago relatives of mine moved to the Welsh borders, and I began to spend long, exhilarating days walking the heather- and bracken-clad uplands of the Berwyn Hills. I liked to gaze down from Thomas Telfords nineteenth-century trunk road, now the A5, at a point known as Pont Glyn-diffwys. There, the land plunges hundreds of feet to the fast-flowing River Ceirw, and human life is tucked away in narrow lanes and hamlets. I tramped across moorland as the bracken turned to autumn gold and grouse took to the air, squawking in alarm. And I followed damp sheep tracks up steep river gullies overhung by ferns and moss.

Such a landscape seizes the imagination: its impossible not to wonder how it came to exist. But as I started to read about the regions past, one place in particular kept drawing me back. On the western flank of the Berwyns, where the land drops gently towards the wind-flecked waters of Lake Bala, there are a series of moss-draped pits and quarries. Once upon a time, blocks of dull grey limestone were dragged out of the earth here to build nearby farms and outbuildings. The spot is known as the Gelli-grin, an old Welsh term meaning parched or withered woodland. It isnt much to look at. Nevertheless, I learned it had played a remarkable role in the effort to unravel the history of our planet.

When nineteenth-century mining engineers and naturalists first started to classify the limestones, chalks and clays that cover much of England, the Welsh hills along with much of upland Britain remained a complete mystery. They were widely acknowledged to be old, perhaps among the oldest rocks in Britain, and were therefore presumed to hold the key to such questions as the age and origins of the Earth, and when and how life had begun: controversial matters in Victorian Britain. And yet there was a maddening problem. The rocks themselves were so twisted and apparently chaotic, the strata so difficult to trace, the fossil record so slender and obscure that they defied all attempts to place them in any order. As a result, a jumble of very different minerals was lumped together in a holdall category known as the Greywacke, an anglicisation of the German mining term Grauwacke, meaning grey earthy rock. By the early 1800s this limbo category for the reception of everything that was ancient or obscure in the geology of Britain had become one of the great challenges facing the developing science of geology.

Amid all this obscurity there appeared to be one coherent and identifiable bed of stone that offered a clue to the meaning of the Greywacke: the band of limestone running through the Gelli-grin. But as some of the greatest geologists of the nineteenth century attempted to use it to unlock its secrets, tracing the faint band of limestone as it snaked its way through the rocks of north Wales like the stripe in a tube of toothpaste, they found they couldnt agree on what it was telling them.

First into the field was the Rev. Adam Sedgwick, a brilliant but troubled Cambridge University professor dogged by ill health and bouts of depression. He had an exceptional talent for reading the rocks, but owing to some mysterious inner impediment was incapable of putting his ideas down on paper. Hard on his heels came Roderick (later Sir Roderick) Murchison, a retired soldier and ambitious socialite who treated geological fieldwork as a military campaign and conducted forced marches along Wenlock Edge and central Wales with the help of copious quantities of laudanum and the bemused support of the local gentry. For Murchison, conquering the history of the rocks was akin to conquering Africa or India: a manifestation of Britains imperial glory.

During the 1830s these improbable companions formed one of the great scientific partnerships of the nineteenth century. Together they painstakingly mapped large areas of the Welsh Greywacke and followed the strata south as they dipped under the Severn Estuary and into Devon and Cornwall. But at the Gelli-grin they hit a band of rock that, for all its apparent clarity, they simply couldnt agree upon. Their difference of opinion at first a hairline fracture so subtle that neither really noticed it became increasingly acrimonious. The collaboration, initially so fruitful, collapsed, turning friend against friend, colleague against colleague, and for the next thirty years divided the Victorian scientific community.

Resolution had to wait until the 1860s, when a young provincial school teacher and amateur geologist called Charles Lapworth began his own investigation into the ancient rocks. He started tracing a little-understood family of fossils known as graptolites across the hills of the Scottish borders. His meticulous examination of the graptolites enabled him to definitively classify the Gelli-grin limestone and, in doing so, finally make sense of the Greywacke.

As I sat in the cool green shade of the Gelli-grin one summer day, with a chainsaw buzzing far away in the valley below, I became caught up in this remarkable story and its curious cast of characters. And so I decided to reconstruct their journeys around some of the most rugged parts of Britain.

I climbed the bare slopes of the Berwyn Hills with Adam Sedgwick and followed him west across the empty expanses of the Denbigh moors and into Snowdonia. I tracked Roderick Murchison along the Wye Valley and through the Welsh Marches into the green, gently rolling hills of central Wales. And I travelled north to the Scottish borders where Charles Lapworth crawled, sometimes literally on his hands and knees, in pursuit of graptolites.

As I walked in their footsteps I found myself entering the strange, almost entirely masculine world of a remarkable group of scientific pioneers. I became familiar with Sedgwicks curious blend of bonhomie, hypochondria and religious puritanism, Murchisons ruthless ambition and love of king and country, and Lapworths patience, humility and occasional mental fragility. What amazed me was that, apart from a handful of invaluable academic works, their story has never really been told before. Yet it is a deeply involving saga of friendship and rivalry, success and failure, courage and ambition.