PARIS 1928

PARIS 1928

NEXUS II

Henry Miller

Drawings by Garry Shead

Introduction by Tom Thompson

HENRY MILLER

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Paris 1928

Henry Miller

A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9780 86196 697 4 (Paperback edition)

For Tony and Valentine

Ebook edition ISBN: 978-0-86196-905-0

Ebook edition published by

John Libbey Publishing Ltd, 3 Leicester Road, New Barnet, Herts EN5 5EW,

United Kingdom

e-mail:

Printed and electronic book orders (Worldwide): Indiana University Press, Herman B Wells Library 350, 1320E. 10th St., Bloomington, IN 47405, USA

www.iupress.indiana.edu

2012 Copyright John Libbey Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

Unauthorised duplication contravenes applicable laws.

Introduction

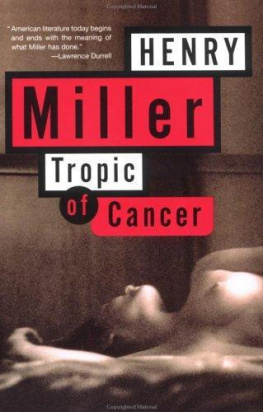

I n 1927, a would-be writer, Henry Miller, opened a speakeasy in Greenwich Village with his second wife June Mansfield. That year, he exhibited his first watercolours and, according to Miller, compiled notes for an entire cycle of autobiographical novels in one day. These Capricorn Notes became a resource and a wellspring which the writer drew on for the rest of his creative life. They became immediately useful in his second period in Paris, (19301939), when he published TropicofCancer (1934), Black Spring (1936) and TropicofCapricorn (1939) and after that, with the publication of the RosyCrucifixion trilogy of Sexus (1949), Plexus (1952), and Nexus (1960). This last was completed in April 1959 and published in France as Nexus I the following year. Millers imaginative commitment to the events recorded in the Notes lasted for most his life, with the writer revisiting the sequence and its unfolding again and again.

Nearly thirty years after its original publication, Grove Press published the first authorized US edition of TropicofCancer in 1961. That same year, Henry Miller, now a writer of international stature, was touring Europe and working on a new book, NexusII. He completed three drafts. The release of TropicofCancer was keeping his publishers busy at the time, defending the author in obscenity trials in different states.

The new manuscript, Nexus II, was a reworking of Millers first trip to Paris with June in 1928, a journey that had taken them deep into the Europe she saw as her homeland. Miller had already travelled over this territory in several works, notably in TropicofCapricorn, where he saw their journey as a metaphor for the sinuous, multi-faceted nature of his relationship with June. When I look up from my machine, my eyes confront the large, many-coloured map of Europe which I have pinned to my wall; it is criss-crossed with rail and steam ship lines, with national frontiers, with indelible prejudices and rivalries. And the very raggedness of its contour all this strain and erosion exemplifies, in my imagination, the conflict that has been going on between Hildred (June) and myself and of which this book is but a map.

With TropicofCancer, BlackSpring and TropicofCapricorn using some of the material in their own incarnations, why we may ask should he have felt the need to revisit it again? What had been left unsaid?

One answer to these questions lies in the unpublished version of TropicofCapricorn, where Miller stated his commitment to a discursive, digressive style, the vital part of me made up by books and writers. They too are in my blood, he wrote, carried along with my living, part of my hate and love. Here, he also described elements creeping in which I am sure no editor would approve of. It is impossible for me to write even the most fantastic tale without mention of books and authors, without extraneous details, as it is called.

Miller was seventy years old in 1961, his memory reignited by this new exploration of Europe. Plainly, he felt it necessary to go over the map again for any new and extraneous details that might affect his understanding of himself as a writer; a status still under attack via the obscenity trials. Nexus II is also a travelogue of sorts, allowing him the chance to include extraneous descriptions and reflections that are not germane to the earlier books. To that extent, it is a re-examination, both of his precarious period as a would-be writer in Paris before the Crash of 1929 and his impressions of the Europe he found on his first visit, memories sharpened by his present situation.

Im a writer a writer of no importance. I havent yet sold a story or an article to any editor. We live by our wits do you know what that means? Weve been hungry for days on end, weve robbed our friends, weve cheated the tradespeople, weve lived a dogs life ever since I decided to be a writer.

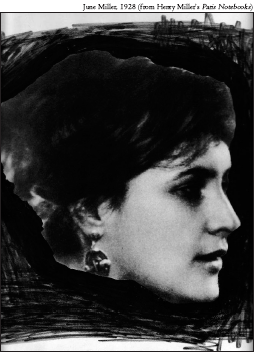

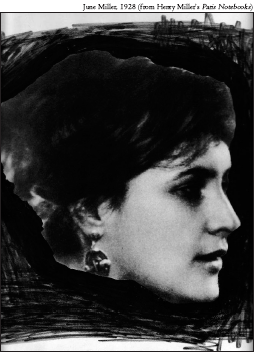

The years preceding this declaration/confession were critical years for Miller. He had fallen in love with June Mansfield in 1923, divorcing his first wife, Beatrice Wickens, in 1924 and leaving behind his 5-year-old daughter Barbara. He married June the same year, leaving work and responsibility behind with the intention of living as a writer. Their partnership was essential to Miller, not just at the personal and creative level but because it was only through Junes machinations that he was able to sell his work at all.

Nexus II opens in the summer of 1928 with Val and Mona (Henry and June) arriving in Paris on money provided by Pop, one of Junes many admirers. Pop believed June was the author of Millers novel Moloch, which had been written in installments and passed off to Pop as hers. The couple spent more than a year in Europe on this visit, travelling to England, France, Belgium, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary and Poland.

Junes persona was self created. Her birth name was Smerdt, a Russian word for death, but her preferred name was June Mansfield, which she said was from mans field or cemetery. As Millers confidant, the photographer Brassai noted, shed worked as a B-girl at a gay nightclub for both sexes in Greenwich Village, and was courted by some of the butchest lesbians around. Brassai recalled that June herself preferred seraphic-looking women and, one evening fell madly in love with a young Russian woman whom Miller would call Anastasia Henry wondered if they were planning to run away, for he knew they dreamed of Paris and of Montparnasse.

Miller described himself at the moment of his departure for Paris as An expatriate from Brooklyn, a francophile, a vagabond, a writer at the beginning of his career, naive, enthusiastic, absorbent as a sponge, interested in everything and seemingly rudderless. This trip was to be his first foray into the dreams and yearnings hed conjured in their life on the fringes of New York society in the 1920s. It was underpinned by the tantalizing uncertainty of his relationship with June, whose feints, ploys and subterfuges will be familiar to all readers of Miller. Foremost of these, in this period, concerned her relationship with Anastasia or Stasia, the character based on her lover, Jean Kronski. Jean had moved in with the couple in 1927 and her surprise departure for Europe with June some months later had left Miller enraged, bereaved and helpless. This abandonment prompted him that July to draft a grand sketch of his life and his obsession with June, now known as the