Brassas text and photographs copyright 1975, 2011 by Gilberte Brassa and ditions Gallimard

Translation copyright 1995, 2011 by Arcade Publishing, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brassa, 18991984.

[Henry Miller, grandeur nature. English]

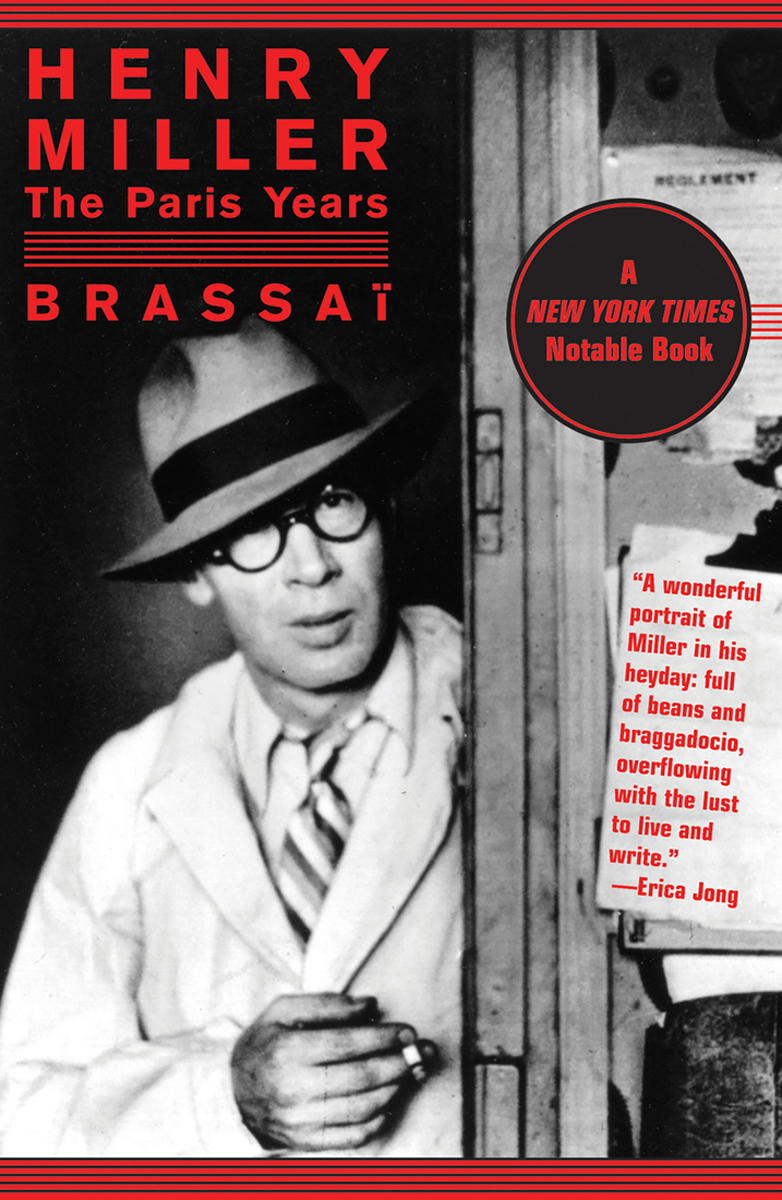

Henry Miller : the Paris years / Brassa ; translated from the French by Timothy

Bent, with photographs by the author,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61145-028-6 (alk. paper)

1. Miller, Henry, 1891-1980Homes and hauntsFranceParis. 2. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. 3. Paris (France)Intellectual life20th century. 4. AmericansFranceParisHistory20th century. 5. Brassa, 1899-1984Friends and associates. I. Bent, Timothy. II.Title.

PS3525.I5454Z65713 2011

818.5209dc22

[B]

2011002433

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-950994-24-3

To Raymond Queneau

CONTENTS

TRANSLATORS NOTE

Brassas portrait of Henry Millers Paris years ranges freely among, and extracts generously from, Millers works. With the exception of several letters Miller sent him, Brassa has based his citations on translations. Every attempt has been made to locate and use the original though indications werent always clear and a bibliography at the end of the book lists the editions of works employed herein. Sources for some citations, such as those taken from correspondence between Miller and Frank Dobo or from transcripts of conversations between Dobo and Brassa, were not traceable. Quotations from works originally written in French have been translated for this volume; citations refer to the original versions used by Brassa.

HENRY MILLER

I

On the Terrace at the Dme

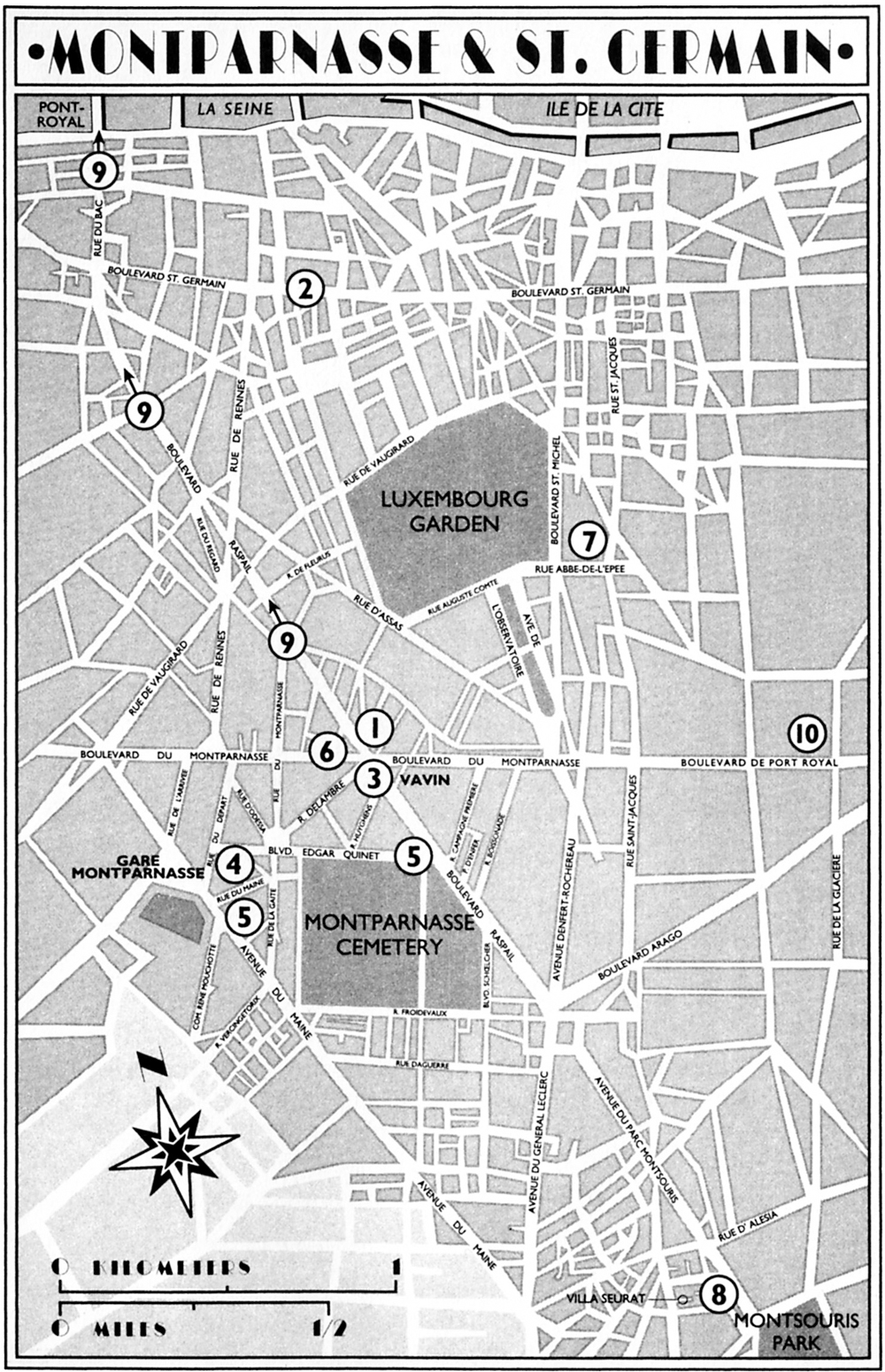

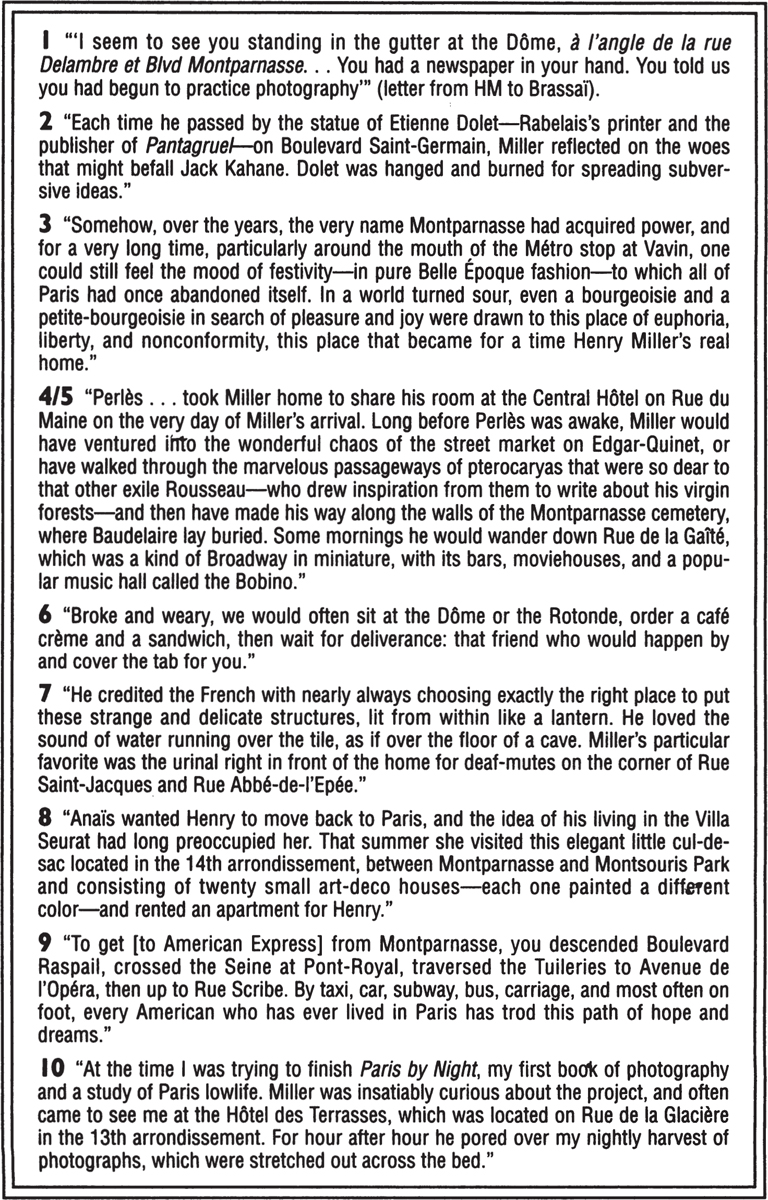

How does my memory of this compare with yours? I seem to see you standing in the gutter at the Dme, langle de la rue Delambre et Blvd Montparnasse ... You had a newspaper in your hand. You told us you had begun to practice photography. It may have been the year 1931. The spot where you stood I see so vividly that I could draw a circle around it. In a letter to me, this was how Henry Miller recalled our first meeting. Its strange, he told me, but with most people we remember neither where nor under what circumstances we met. But I remember the first time you and I met as if it were yesterday.

My memory doesnt quite compare with his. My memory of the first time Henry and I met was that it took place in December 1930, shortly after he had arrived in France. My friend the painter Louis Tihanyi introduced us. Louis was sort of the Dmes PR man everyone recognized his olive green corduroy overcoat, worn to a shine, his wide-brimmed gray felt hat, his monocle, his fleshy lower lip. He was the spitting image of Alphonse XIII minus the pencil mustache. Every night, table by table, Louis worked the crowded Dme terrace, which, beneath the luminous green shade of the trees on the boulevard, was always festive, as if every day were Bastille. Although deaf, and very nearly dumb as well, Louis was the best-informed man in Montparnasse. He knew not only every single one of the regulars, but the measure and worth of each newcomer.

I want you to meet Henry Miller, an American writer, he announced in his abrupt, guttural voice, which somehow always managed to make itself heard over the hum of conversations and the noise from the street.

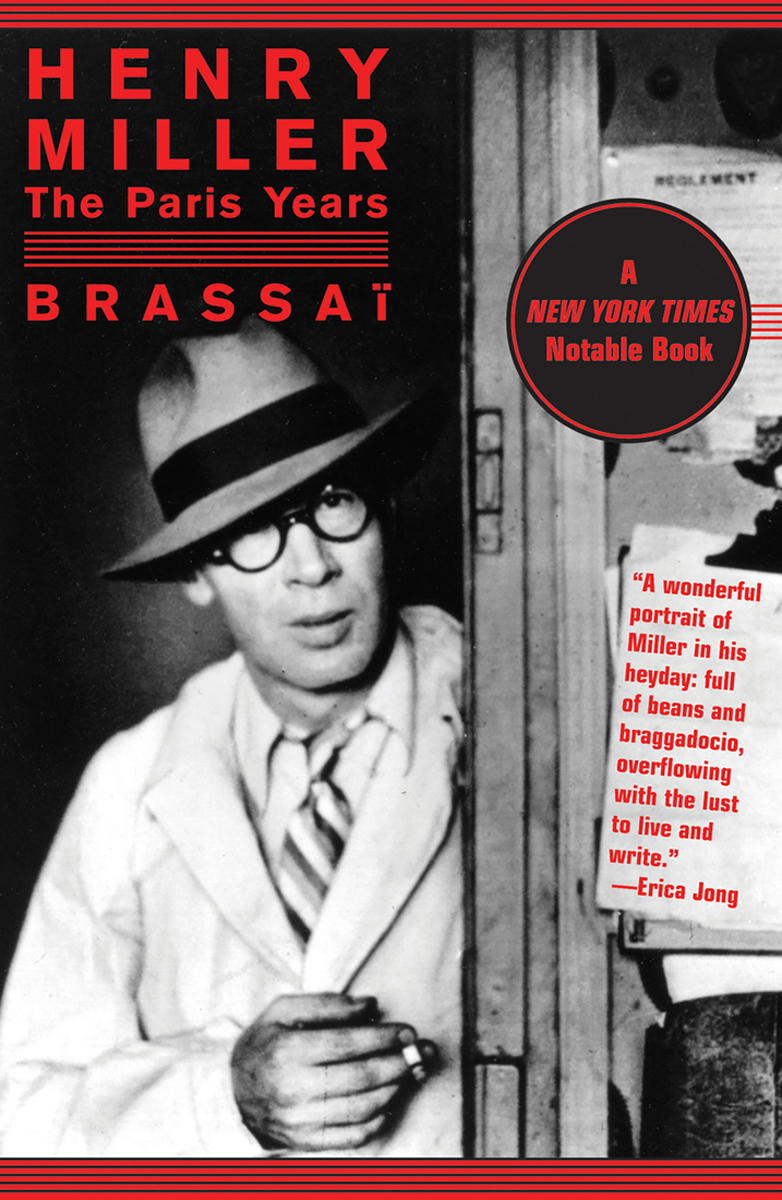

And there was Henry Miller. I will never forget the first sight of his rosy face emerging from a rumpled raincoat: the pouting, full lower lip, eyes the color of the sea. His eyes were like those of a sailor skilled at scanning the horizons through the spray. They always conveyed calmness and serenity, those eyes, and even though their expression seemed as guileless and attentive as a dogs, they lay in ambush behind large tortoiseshell glasses. When we met they were scrutinizing me with curiosity. When he took off his crumpled gray hat, the dome of his bald skull, haloed by silvery hair, reflected the cafs neon lights. He was slender and gnarled, and without so much as one ounce of excess body fat. He reminded me of an ascetic, a mandarin, a Tibetan holy man. Had some makeup artist fit him with a mustache, long gray hair, and a patriarchal beard, Miller, with his crinkled, Asiatic eyes, his strong nose and flared, aristocratic nostrils, would have looked exactly like Leo Tolstoy. I will never forget the first time that I heard his sonorous bass voice warm and virile, punctuated by yesses and hmms, and accompanied by a deep, gentle rumble of pleasure.

June, Henrys wife who would be the Mona and the Mara in his books had been to Paris before him. Shed run away there in 1927 with her Russian friend, leaving Henry behind to mope all by himself in their basement apartment in New York. June had taken up residence in the Princesse Htel, located on the Left Bank near Saint-Germain-des-Prs. When she returned to New York later that same year, loaded down with stories and gifts, Henry thought she looked more beautiful than ever. Her return blotted out the whole tragedy of her betrayal, just as the title of the work he had planned to write about it all changed from Crucifixion to The Rosy Crucifixion. Henry was dying to know all about Paris, and bombarded her with questions. Had she seen Picasso? Matisse? She replied that she hadnt. She had, however, made the acquaintance of Zadkin, Marcel Duchamp, Edgar Varse, Michonze, Tihanyi, and other artists of whose names Miller had not yet heard, although later they were to become his friends. In 1928, having managed to scrape together enough money to do so, June returned to France, and this time she took Henry. They visited nearly every European country and spent a full year in Paris.

Tihanyi met Henry during this first trip, and immediately realized when he saw him again in 1930, during the second trip, that he was not one of those typical rich Americans, ready to buy one of your paintings or treat you to a good dinner, but a somewhat rare thing in Paris in those days a penniless Yankee with neither name, reputation, nor fixed abode. The Paris police would have been within their rights to arrest Miller for vagrancy and haul him down to the station. The mans entire fortune consisted of a toothbrush, a razor, a notebook, a pen, a raincoat, and a Mexican cane that he had brought over with him. I have only physical, biological problems, he tells his friend Michael Fraenkel in one of their

Next page