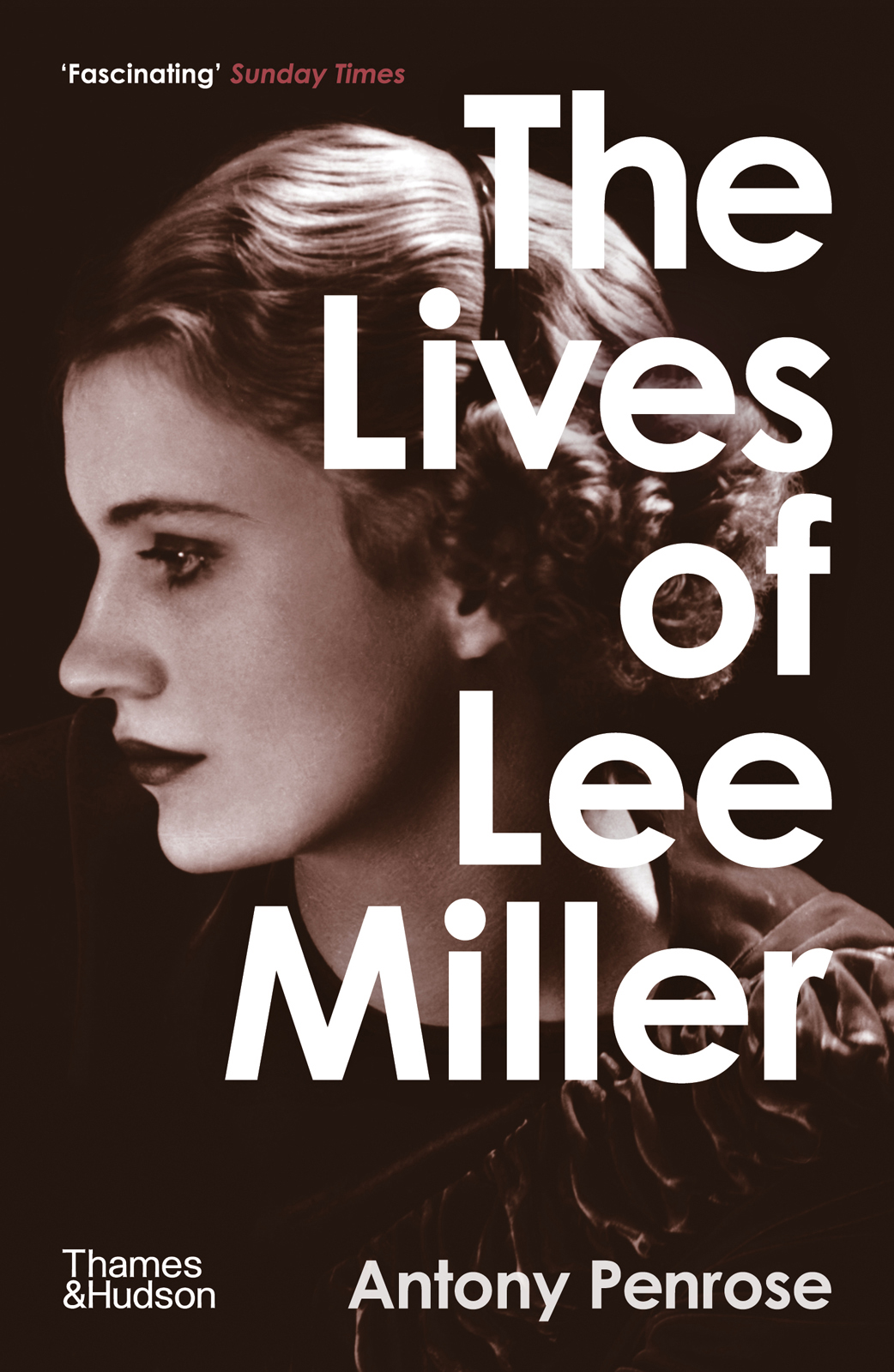

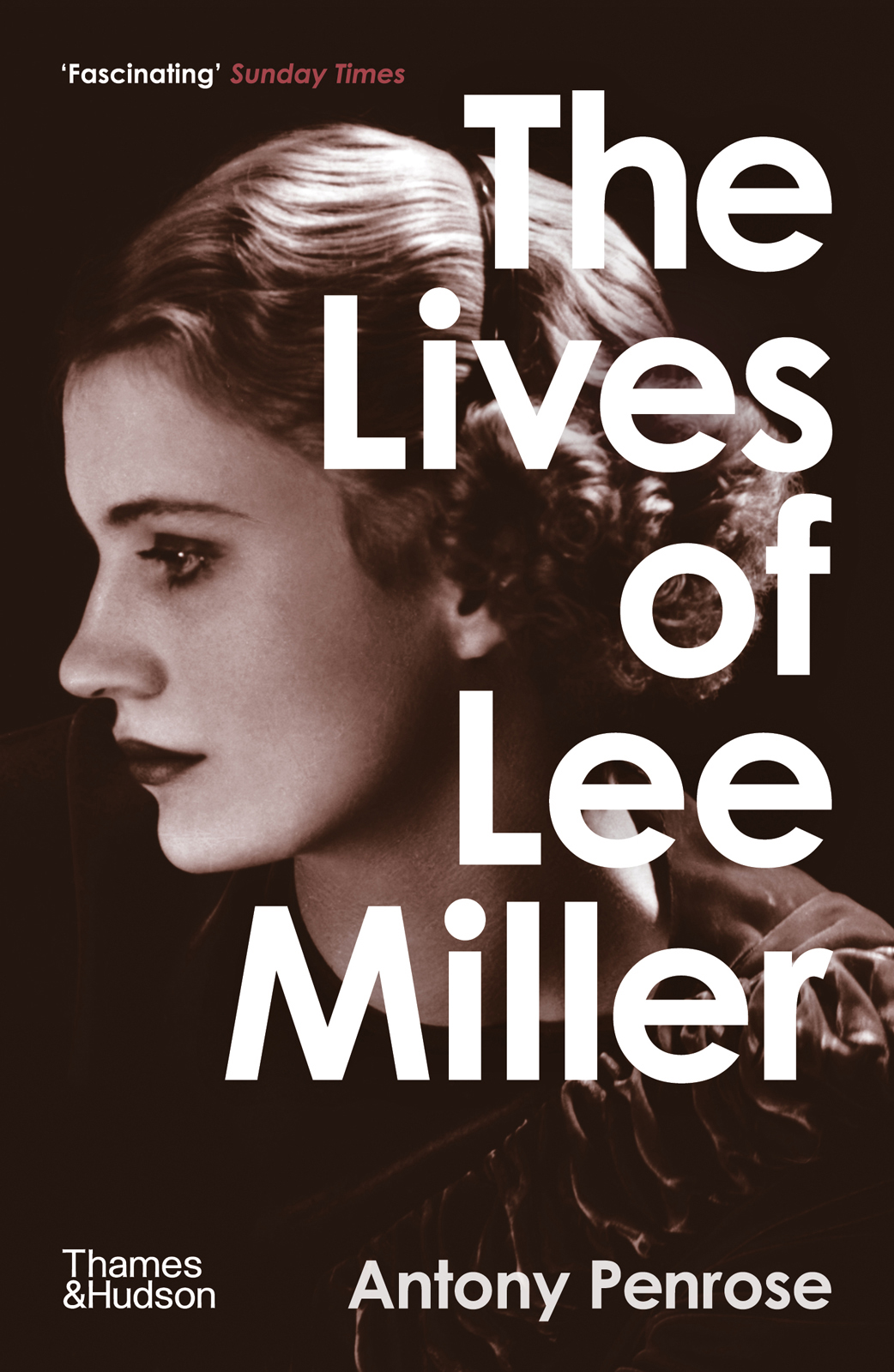

About the Author

Antony Penrose is a writer, photographer, sculptor and film maker. The son of Lee Miller and Sir Roland Penrose, he is founder and co-director of the Lee Miller Archives and The Penrose Collection at Farleys House and Gallery Ltd., his parents former home, now a historic artists house. He has written a number of books, including Lee Millers War, also published by Thames & Hudson.

Contents

L ee Miller, fashion model. Lee Miller, photographer. Lee Miller, war correspondent. Lee Miller, writer. Lee Miller, aficionado of classical music. Lee Miller, haute cuisine cook. Lee Miller, traveller. In all her different worlds she moved with freedom. In all her roles she was her own bold self.

A paradox of irascibility and effusive warmth, of powerful talent and hopeless incapability, Lee rode her own temperament through life as if she were clinging to the back of a runaway dragon. Sometimes the dragon triumphed and Lee was plunged into bleak weeping despair, but mostly she took control and won a close-run victory against herself first and adversity second. Her successes always left an enduring impression. She loved to learn, create or take part, and then move on to something else. Some of her jags, as she called her current obsessions, would last only days; others stretched for years. Photography was her supreme jag, and she deserted it only when, after thirty years, she had exhausted all its abilities to provide excitement.

Lees spread of interests amounted to much more than the desultory pecking of a dilettante. Whatever she became involved in, her commitment was total and the consequence to herself and others was of only minor consideration. Though Lee had an immense capacity to learn from other people, few can be seen to have had much influence on her. She herself changed little as she moved among the giant-sized characters that peopled her different worlds. The core of her character had been assembled, stamped and sealed for life at an early age under the supervision of a remarkable mechanical engineer: her father, Theodore Miller.

Theodore Miller was descended from a Hessian soldier who settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, after the Revolution. His father was a bricklayer from Richmond, Indiana, but Theodore started his working life as a machine operator making wooden wheels for roller skates. With tenacious application he worked his way into progressively better jobs with the help of qualifications obtained through the International Correspondence School. In later years, when accused of being stubborn, he would dismissively say that stubbornness was just applied determination. This wilfulness, an insatiable curiosity about all things mechanical and scientific, and a completely unabashed manner of asking questions were traits that his daughter inherited.

In about 1895, when Theodore was in his middle twenties, he made up his mind to travel around the world. His limited means took him no further than Monterey in Mexico, where he got a job working in a steel mill. Unfortunately, this great adventure was short-lived. He contracted typhoid and ended up in the local hospital. It was the custom for patients to rely on their families for food, and with no family at hand it was lucky for Theodore that his friends from the steel mill brought him things to eat from time to time, and that the nuns from a nearby convent were kind enough to overlook his atheism and supplement his meagre rations.

As soon as he was well enough to stand the journey he returned to the United States. Career opportunities caused him to shelve his travel plans and he first took a job as foreman with the Mergenthaler Linotype Company in Brooklyn, New York, and then moved on to the Utica Drop Forge and Tool Company where he was rapidly appointed General Manager. Adding to the attractions of Utica was a Canadian nurse at Saint Lukes Hospital Florence MacDonald. A kindly and industrious person, she was the daughter of Scottish-Irish settlers from Ontario. Their courtship was a long one, because Theodore refused to consider marriage until he was in a sufficiently advanced position to offer his wife-to-be a secure home. To help while away the years of waiting, he persuaded her to indulge his most cherished hobby photography. Posing nude for him in a discreet but self-assured manner, she became the subject for an elegant sepia-toned portrait in the exact mode of the period.

At this time the De Laval Separator Company in Poughkeepsie was beset with labour difficulties and strikes, and, hearing about the bright young man in Utica who had rare managerial talents, sent for him. As soon as he was appointed Works Superintendent, Theodore radically improved the workers pay and conditions, firing those who remained unsatisfied.

In 1904, after a years separation while Theodore got established in Poughkeepsie, he and Florence were married. She did not immediately take to life in her new home; while waiting in Utica she had met someone else and could not be sure that she had made the right choice. With true pragmatism, Theodore sent her back to Utica to make up her mind. She returned a few weeks later completely reassured that she preferred the husband she already had.

De Laval was the largest and most prestigious business in the town with about eleven thousand employees and a massive sales network. It may have been the newfound status of their company connections that brought the young couple to the flattering attention of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Florence was invited to join this elite social group founded on the filiation of loyal Americans. She gratefully accepted and all was well until they came to investigate her ancestry. Alas, her parents were Canadian and had therefore fought against the revolutionaries, and, worse still, Theodores parents were descended from the Hessian mercenaries sent to quell the rebels. Florences application was summarily dismissed, but the incident remained forever the key family joke.

John MacDonald was their firstborn, in 1905, and on 23 April 1907 Elizabeth was born. To begin with she was called Li Li; then she became Te Te to her parents; but everyone else always knew her as Lee. She was followed by Erik in 1910. Theodores talent and industry earned his promotion to Works Manager, and the family moved to a small farm of 165 acres outside of Poughkeepsie on the Albany road.

The management of the farm was left to a Canadian, Uncle Ephraim Miller, who despite his surname was no blood relation. Uncle Ephraim did not share Theodores love of innovation, preferring the time-honoured methods. This was unfortunate, for though Theodore was known to be wonderfully tolerant of other peoples views, failure by another to grasp progressive methods was absolute anathema to him. Uncle Ephraim had to go, and was eventually replaced by a more forward-looking manager, Jimmy Burns. The farm quickly became the test bed for all the new milking and cream-separating equipment produced by De Laval.

Next page