Table of Contents

GENDER AND CULTURE SERIES

GENDER AND CULTURE

A Series of Columbia University Press

Nancy K. Miller and Victoria Rosner, Series Editors

Carolyn G. Heilbrun (19262003) and Nancy K. Miller, Founding Editors

For a complete list of books in the series see

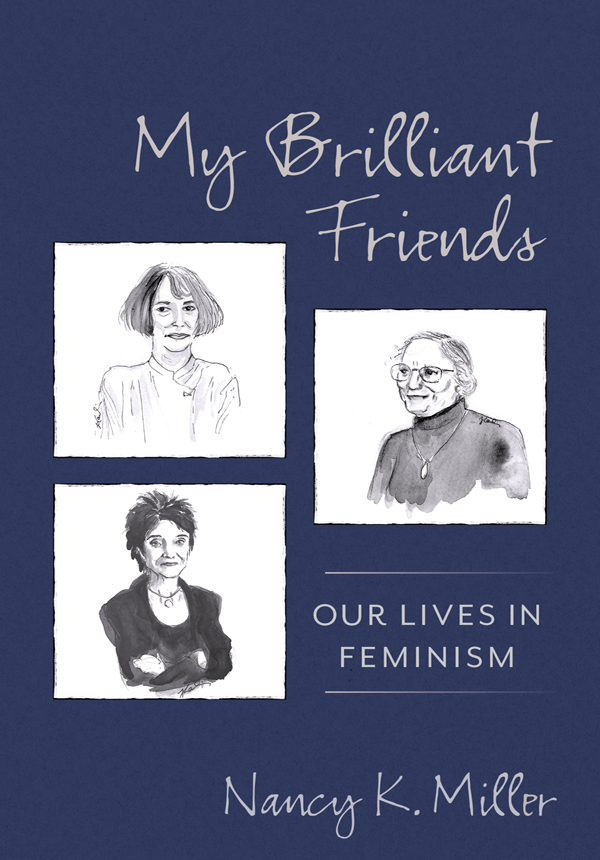

OUR LIVES IN FEMINISM

Columbia University Press

New YorkColumbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54894-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miller, Nancy K., 1941 author.

Title: My brilliant friends: our lives in feminism / Nancy K. Miller.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018022549 (print) | LCCN 2018026082 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231548946 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231190541 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Miller, Nancy K., 1941 | FeminismUnited States. | Female friendshipUnited States.

Classification: LCC HQ1421 (e-book) | LCC HQ1421 .M55 2018 (print) | DDC 305.420973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018022549

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover and interior illustrations by Jojo Karlin

Cover and book design: Lisa Hamm

As is well known, the ancients thought friends indispensable to human life, indeed that a life without friends was not really worth living.

Hannah Arendt, Men in Dark Times

I can lose anything! At nine, I bragged about my losses even though I was always punished for them. I remember the punishments, not the boasting. But pride in my losing streak featured in my mothers set pieces, whenever she recalled my character flaws, long after I had left home. I can imagine making the claim though, in a moment of bravado, standing up to her rage. Maybe it was a disclaimer: I cant help it; its not about you, pushing past shame.

Did this history explain my panic on the disappearance of a pair of gold earrings a few summers ago in a little house we owned then near Stony Brook? One morning, just as I always did, I reached for the earrings on the bedside table where I had left them the night before, but they had vanished. I stood there, bewildered, fearful, expectingwhat? A punishment that never came, nor did the earrings reappear.

Naturally, they were not any pair of earrings. They had been handmade by Resia Schor, my friend Naomis mother, who was an artist and a jeweler. Sandy, my husband and a graduate school friend of Naomis, had bought them for me as a birthday present at least thirty years earlier. The gift of the earrings marked a moment in my friendship with Naomi when our bond was new and the two of us were engaged in a phase of intense identification and competition, with each other, but alsothis is harder to explainfor each other.

The earrings were shaped like the outline of a daisy with uneven edges that bore the makers handthin, flat, and elegant, each gold flower perfectly covered the two asymmetrical sets of holes in my earlobes. I always traveled with this pair because they were easy to wearwith anythingand comfortable. I am wearing them in my last, expired, passport picture and in my author photo.

The losing score: one pair of earrings, three close friends: Carolyn Heilbrun, Naomi Schor, Diane Middlebrook.

From 2001 to 2007, nearly a decade of grief to open the new millennium.

The stories of these three life-changing friendships all bear the burden of loss. I cannot look back without feeling weighed down by their endings: suicide, cerebral hemorrhage, cancer. Its hard to resist mourning, and mostly I dont, but I want also to return to beginningsthe excitement of unfoldingsand, in retrospect, to remember how these friendships, two long-lasting, one brief but intense, shaped my emotional biography and the map of my brain. I could not have figured out who I was without them. Simply, not that its ever simple, for starters, Ill say that each of these women made my life worth living because we believed in each other. I will cop to Hallmark card sentiment for now.

The shape of these stories has a lot to do with the luck of history, the passions of seventies feminism that challenged the academic world in which we all worked. But in the end, what mattered was how we grew into ourselves together with that luck. And how we lived our relationships had as much to do with the tapestry of our sometimes inchoate desires as our politics. Despite the rhetoric of sisterhood we embraced, a bond meant to transcend negative emotions, we suffered our share of envy and competitiveness, emotions a familiar part of the feminine palette we had inherited. The feelings were not always beautiful, and were hard to root out, but like so many other women, we came to view our friendships as a crucial piece in a new narrative.

Friends mourning their losses have offered the world most of the autobiographical accounts of friendship, and the most beautiful. Elegy is the preferred mode of friendship memorialization for men, Montaigne famously, but also for women. Theres nothing like death to offer the kind of closure that allows for shapely storytelling. But elegy is also one sided. The survivor tells the story. Even if the letters and emails in my possession carry the voice of the missing friend, inevitably I am the editor, as well as the teller, for two, even if I wantand I doto be a faithful reporter.

Theres a certain solace in writing about loss, too, of course, because its a way of coming to terms with mortality. As long as you are doing the writing, you are rehearsing the losing; unlike the friend, you are still there. You are the mourner, after all. But what happens when you start losing yourself? When, while fixed on the other, you discover that your position, secured among the living, is unstable, unsure? You may have imagined yourself safely on the side of the living, and then suddenly, like me, you are on the verge, possibly, of disappearing yourself. Not long after I began to write the stories of these friendships, I was diagnosed with advanced-stage lung cancer (incurable but treatable, as my laconic oncologist put it when he delivered the prognosis). While I was struggling to understand what that might meanhow long would I live? how I would live?I wanted to abandon this project. I had been writing from the place of the one who remained behind. Suddenly I was mourning myself.

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press New York