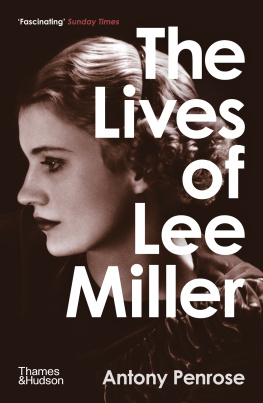

Also by Carolyn Burke

Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy

This Is a Borzoi Book Published by Alfred A. Knopf Copyright 2005 by Carolyn Burke

Photographs by Lee Miller, Theodore Miller, and David E. Scherman are Lee Miller Archives, England, 2005. All rights reserved. Photographer unknown Lee Miller Archives, England, 2005. All rights reserved. Photograph by Roland Haupt Artists Estate courtesy of the Lee Miller Archives, England, 2005. All rights reserved.

This book contains quotations and extracts from letters, manuscripts, and other documents the copyright in which is owned or controlled by the Lee Miller Archives and may not be reproduced in any way, stored in a retrieval system, or copied without the prior consent of the Lee Miller Archives (www.leemiller.co.uk). The photographic images by Lee Miller, Theodore Miller and David E. Scherman, together with other materials authored by Lee Miller, reproduced in this edition have been kindly supplied by the Lee Miller Archives (www.leemiller.co.uk) with the cooperation of Antony Penrose, Director; Carole Callow, Curator & Photographic Fine Printer; and Arabella Hayes, Registrar, and the staff of the Lee Miller Archives. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Owing to limitations of space, all additional credits may be found on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burke, Carolyn.

Lee Miller : a life / Carolyn Burke.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76663-2

1. Miller, Lee, 19071977. 2. PhotographersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Models (Persons)United StatesBiography. I. Title.

TR140.M55B87 2005

770.92dc22

[B] 2004043844

v3.1

For Valda

I want to have the utopian combination of security and freedom, and emotionally I need to be completely absorbed in some work or in a man I love. I think the first is to take or make freedom, which will give me the opportunity to become concentrated again & just hope that some sort of security follows & even if it doesnt the struggle will keep me awake and alive.

Lee Miller to Aziz Eloui Bey, November 17, 1938

I keep saying to everyone, I didnt waste a minute, all my lifeI had a wonderful time, but I know, myself, now that if I had it over again Id be even more free with my ideas, with my body and my affections.

Lee Miller to Roland Penrose, September 9, 1947

Contents

Introduction

L ee Miller was one of the most remarkable, and underrecognized, photographers of the last century. At their best, her images put head, eye, and heart on one line of sightto borrow a phrase from her friend Henri Cartier-Bresson. Like him, Lee Miller captured those decisive moments when reality seems to compose itself for the camera, when the visual world speaks. But because she did not pursue a conventional career, her reputation, until recently, has been eclipsed by her legend, and the famous men who helped construct it.

While it is true that Lee Millers early work in Paris recalls that of her lover Man Ray, it was uniquely her ownfull of startling perspectives and witty surprises. In Egypt, her home in the mid-1930s, her unforced Surrealist eye saw familiar and unfamiliar sights through the skewed lens of her expatriation. In the 1940s, her World War II coverage for Vogue conveyed the urgency of combat, the horror of the death camps, and the wars impact on ordinary livesthe collateral damage that gripped her long after it came to a close.

That Lee Miller was also one of the most beautiful women of the twentieth century has made it difficult to evaluate her work in its own right. Her astounding good looks seem to get in the way. For many, her beauty is at war with her accomplishment, as if the mind resists the thought of a dazzling woman who is a first-rate photographer.

One might even say that there are too many portraits of Lee Miller by better-known artists. Edward Steichen launched her as a model; Man Ray photographed her, whole and in parts, as his perversely enchanting muse; Jean Cocteau cast her as the spellbinding classical statue in his film Blood of a Poet; Picasso painted six portraits of her as a Provenal wench whose bare breasts inspire reveries of sexual freedom; Roland Penrose charted his erotic relations with her in a series of paintings that range from ecstatic to melancholy.

Mesmerized by her features, we look at Lee Miller but not into her. We think of her as a timeless icon. To this day, her life inspires features in the same glossy magazines for which she posedarticles explaining how to re-create her look. This approach turns the real woman into a screen on which beholders project their fantasies. Looking at her this way perpetuates the legend of Lee Miller as an American free spirit wrapped in the body of a Greek goddess (in the words of her friend John Phillips) while underplaying her lan, the imaginative and moral energy that magnetized those who knew her, often to their cost.

In Lee Millers time, her admirers were equally spellbound by her beauty, but they also saw her as an incarnation of the modern womanin the United States of the twenties, as a quintessential flapper; in Paris of the thirties, as a subversive garonne or a maddeningly free femme surralisteone who sparked creativity in others but played the role of muse only when it suited her, and sought, despite her lovers objections, to keep her energy for herself.

Breaking free of conventional roles for women, whether in traditional or avant-garde circles, Lee Miller stirred up trouble for herself and those who loved her. Like screenwriter Anita Loos and actress Louise Brooks (whose careers she followed), she helped reshape womens aspirations through her embrace of popular culture, starting with her appearances in Vogue after her accidental discovery, in 1927, by Cond Nast. At the same time, she pursued a self-directed training in art, stage design, photography, and, later, politics, all of which inform the incisive dispatches she wrote in the 1940s in her unexpected, and defining, role as Vogues war correspondent.

Lee Millers movement from model to combat photojournalist is perhaps the most remarkable metamorphosis in a life full of self-reinvention. Who else has written equally well about GIs and Picasso? the head of U.K. Vogue asked when she returned to London after the war. Who else can get in at the death in St.-Malo and the rebirth of the fashion salons? Who else can swing from the Siegfried line one week to the new hip line the next?

Two portraits of Lee Miller, emphasizing hats rather than hemlines, suggest her significance in her own time. The first, a drawing by Georges Lepape, appeared on the cover of Vogue a month before her twentieth birthday. Posed against Manhattans night sky, she stares into the future from beneath her helmetlike cloche hatthe incarnation of what it meant to be moderne.

Nearly two decades later, Vogue ran a striking shot of Lee Miller in uniform wearing a U.S. Army helmet: one can read in her eyes the imprint of the wounded and dying soldiers she had just photographed, for her first illustrated report on the Normandy invasion. These images suggest her exceptional range. The woman who inspired artists to depict her as the quintessential flapper became the photographer whose war images, like those of her colleague Margaret Bourke-White, still have the power to set our hair on end.