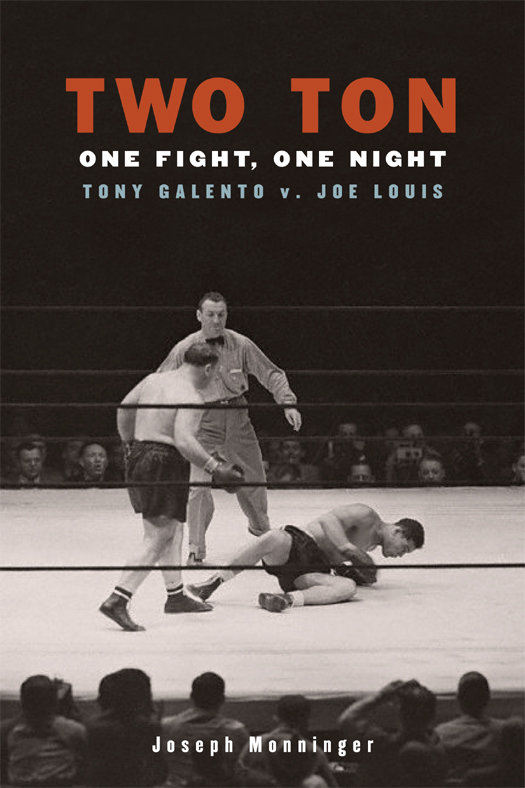

Copyright 2006 by Joseph Monninger

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to:

Steerforth Press L.L.C., 25 Lebanon Street

Hanover, New Hampshire 03755

The Library of Congress has cataloged the paperback edition as follows:

Monninger, Joseph.

Two Ton : one fight, one night :

Tony Galento v. Joe Louis / Joseph Monninger. 1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Galento, Dominick Anthony, 191079

2. Boxers (Sports) United States Biography.

3. Boxing matches New York (State) New York.

4. Louis, Joe, 191481 I. Title.

CV 1132. C 3 M 66 2006

796.83092 dc22

[ B ]

2006012828

eISBN: 978-1-58642-209-7

v3.1

For Peter Johnson

Contents

One plays football, one doesnt play boxing.

JOYCE CAROL OATES , On Boxing

Oh, I knew that if I kept on fighting, some guy would come along and take the title away from me, but not this guy, never tonight.

JOE LOUIS

Preface

I N THE END , he lost his foot to diabetes, then his legs, and finally his life. Two Ton Tony Dominick Galento died on July 22, 1979, a ghost hero to the kids of Orange, New Jersey. Before the end, he wrestled octopuses for promotions, appeared as a tough in the Brando classic On the Waterfront, and wagered ten dollars he could eat fifty hot dogs before fighting a heavyweight match. He won the bout in four rounds, pulverizing a hapless Arthur DeKuh. He went out to dinner afterward on the ten bucks he won, the food washing down his sizable gullet on a tide of beer. He fought the dirtiest fight in the history of modern boxing against Lou Nova in Philadelphia, September 1939, and maintained such a reputation that other boxers sometimes fouled him in their rush to prove themselves equal to the street fight they had entered. In 1931 he knocked out three opponents in a single night, stopping Frankie Kits and Joe Brian in one round each, and tossing away Paul Thierman in three. Between rounds, he drank beer.

Out of the ring he went through managers like hand towels, finishing with at least nine men who tried to arrange his business for him. Even the great Jack Dempsey, boxing immortal and Galentos manager from 1933 to 1934, could not calm him. Galento lived as he fought, a bus wreck, a cracked window. Days before his final major fight, a scheduled ten-rounder with Max Baer, Tonys brother, Russell, asked him for a free ticket. When Tony told him to stand in line with the others, his brother threw a beer bottle at Tonys head. Bleeding from a three-inch gash on his chin, Tony had it stitched up by Doc Stern, a physician often called on to remedy Two Tons wounds. Tony fought a few days later, the stitches removed directly before the opening bell, waddling in against Max Baer in Washington, DC. A broken knuckle stopped him that night, but the bottle wound opened too, bleeding thirty seconds into the fight.

Like Jake LaMotta, a contemporary, he tried his hand at standup comedy, played bit parts in the movies, trained on spaghetti and meatballs. He did his road work at night, saying, I fight at night, dont I? He made one successful comeback, knocking out Herbie Katz in the first round in 1943 and Jack Suzek in Wichita the next autumn. After fifteen years, and a 79-26-5 record, he hung up the gloves and spent the remainder of his life behind the bar of his tavern in Orange.

He is quoted in Bartletts: Ill moida da bum, he said. He said it often, and often of his betters.

But in the summer of 1939, on a Wednesday in June at Yankee Stadium, Two Ton Tony Galento fought Joe Louis, the finest heavyweight of his generation. The weather, cloudy, with a moderate southerly wind, proved no factor for Louis. The champ, a trim six-footer at 200 pounds, had the ideal body type for a heavyweight of that era. Called the Brown Bomber, or the Dark Destroyer, Louis came to the fight in magnificent shape. Galento, on the other hand, stood a mere 58 and weighed a flabby 240 pounds. The heat of a New York summer did not favor him. The odds against Galento ran 6 to 1, though a Gallup poll published by the New York Times reported that 47 percent of the crowd pulled for Galento. Boxing fans love an underdog, and Galento, put forward as the bum of the month for Joe Louis to consume, fit the bill.

They fought for a $400,000 purse, a remarkable sum in 1939. Louis was promised 40 percent to Galentos 17 percent. The gates opened at 6 PM . NBC broadcast seven preliminary four-round bouts, not one ending in a knockout. By nine oclock J. Edgar Hoover had found his seat at ringside, as had Supreme Court Justice John McGeehan. Heavyweight Gene Tunney, John Hamilton, chairman of the Republican National Committee, Governor Bricker of Ohio, Governor Baldwin of Connecticut, Mayor LaGuardia, Governor A. Harry Moore of New Jersey, Mayor Frank Hague of Jersey City, Postmaster General James A. Farley, Governor Herbert Lehman of New York, Bill Terry, manager of the Giants, and Jack Benny were spectators. Mrs. Lillian Brooks, Joe Louiss mother, attended, as did Mary Galento, Tonys wife. New York Police Commissioner Valentine assigned six hundred patrolmen to control the crowd inside the stadium.

Across the nation, forty million people tuned in to NBC to hear a title bout, arguably a greater sporting event in the 1930s than the World Series. An estimated 24.5 million families owned a radio, adding up to eighty million potential listeners. In the summer of 1939, the thirty-three million radios in operation equaled the total number of automobiles and telephones combined. At that time, radio provided the largest audience in history to advertisers. Appearing on radio turned a man into a household name.

A contender, a man shaped like a beer barrel, a crude, raw Italian American from Orange, New Jersey, Galento contained in his left hook the elements of the American dream. Any man could be champ. His charisma stemmed from his role as representative of the underbelly of American society, and from his humor. Years later, watching Muhammad Ali talk the world into giving him a shot at the title, Galento claimed to be the original master of ballyhoo, the first boxer to understand fully the usefulness of humor and braggadocio. The fraud, of course, is seldom a fraud to himself, and deep in his heart Galento believed he could defeat the Brown Bomber.

A palooka, a thug, a vibrant appetite of a man, he scrapped his way out of the streets and into the brightest light in American life. For two splendid seconds he stood on the canvas at Yankee Stadium, the great Joe Louis stretched out beneath him, champ of the world, the toughest man alive, the mythical hero of the waterfront, of New Jersey, of an American nation little more than a year away from war. Ill moida da bum, hed predicted. And though Joe Louis was no bum, Two Ton Tony had been as good as his word.

F ETCH IS THE DISTANCE over which wind works on water: the longer the fetch, the greater the wave-building action. On a typical New Jersey summer day, the fetch stirs from the Carolinas, blowing northward along the coast, bringing humidity and coolness off the ocean for a mile or two inland. On certain days in June, a marine layer, extending halfway across the state, keeps the ocean counties of New Jersey cool while the inland cities and boroughs swelter. By eleven oclock most mornings a sea breeze begins, fueled by the cooler ocean air streaming inland to replace the rapidly rising heated air over the land. When the two small fronts meet and neutralize one another, the day can become unbearably cloying, a glued heat touching everything, the air trapped in the small leaves of garden hosta and Japanese maples, the roadways turning to tar and shimmering waves of lilac gasoline spills.

![Louis de Montfort - The Saint Louis de Montfort Collection [7 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/265822/thumbs/louis-de-montfort-the-saint-louis-de-montfort.jpg)