Foreword

BY AN ACCIDENT OF time and place, I grew up on an American frontier. I was born in 1900, ninety-six years to the day after Lewis and Clark left St. Louis on their expedition across the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase; but my formative years were spent under circumstances not far different from those my great-grandfather knew in western Pennsylvania a century earlier, when Conestoga wagons were still hauling freight over the Alleghenies into the raw, new Ohio country. In that sense, I was born old. I am a kind of bridge between an almost legendary past and a fabulous but often worrisome present. In a way, I am my own grandfather, or even my great-grandfather. In terms of social history I have lived close to one hundred and fifty years, simply because I grew up on an island of isolation in eastern Colorado.

As a result of strange eddies in the migration of a restless people, eastern Colorado and western Kansas were virtually untouched by the whole nineteenth century. After Lewis and Clark, the trappers and traders ranged the whole area from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast. Then the Army, following the trappers trails and often guided by the trappers, explored that country. In 1836 a ragged frontier army won freedom for Texas. A decade later another motley army won a war for California. Gold discoveries set off a series of mass migrations, to California, to Montana, to the Denver area. The Mormons made their stark trek to Utah, not for gold but for land and freedom from persecution. And after the Civil War the Texans, cattle-poor and rawhide-tough, trailed their long-horn herds north across hundreds of hostile miles to the railroad pushing its way westward across Kansas.

In their haste, these rushes and treks and trailings detoured or leap-frogged vast areas, some of which became virtual islands of isolation in a shallow sea of settlement. Those islands, isolated geographically and doubly victims of the time and culture lag, east to west, which was so pronounced before the era of national magazines, newspapers and radio, became our last frontier. Eastern Colorado was one of those islands.

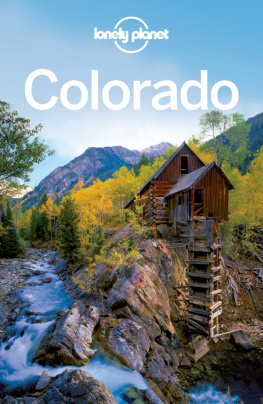

That high, wide and lonesome land is roughly two hundred miles square, an arid, treeless, short-grass upland with few live streams. To the north lies the Platte River, along which emigrants followed the Oregon Trail. To the south lies the Arkansas River and the old Santa Fe Trail. To the east is central Kansas, long accepted as the western limit of feasible agriculture. To the west is the barrier of the Rocky Mountains.

No major emigrant trail ever crossed that area. It was too dry, and the Indians were too fanatically hostile. For years a large part of it was an Indian reserve, and it was the range of one of the last great buffalo herds. In 1877, the year after Colorado was admitted into the Union, President Rutherford B. Hayes called those high plains an unsalable desert, unfit for human habitation, and recommended that it be set aside as a grazing reserve, to be tamed by the stockmen if they ever needed the grass enough to undertake the job. His recommendation was ignored, but the areas character had changed very little when my father decided, in the spring of 1910, that he wanted to take a homestead there.

We arrived on that unsalable desert by a route that sums up a good deal of frontier history. My fathers people came from Scotland to America before the Revolution and settled in New York State. After the Revolution they moved to the frontier in western Pennsylvania. My great-grandfather, who came to be known as Old Will, was taken from there to Ohio as a child. In young manhood he moved, with his wife and basic possessions, to frontier Indiana. His son, my grandfather, who was known as Young Will, in turn moved west, fording streams and hacking his way through the forests. But by then the frontier was moving swiftly westward; Young Will went all the way to Nebraska. He settled not far from a secondary trail which crossed the Missouri River at St. Joseph, Missouri, and angled north to the Oregon Trail on the Platte.

Young Will Borland, my grandfather, was only casually a farmer; he was by trade a blacksmith and millwright. After a few years on the frontier farm he moved to Sterling, a new community on Nemaha Creek, and set up his forge and built a mill. He was a small bull of a man, five feet six and close to two hundred pounds. He had lost one eye in a boyhood accident, but he was a crack shot with a rifle. He made nails and hinges for the village church, built wagons that would last a farmers lifetime, fed, clothed and schooled a big family, and died in his fifties. Two of his sons became blacksmiths, two became railroad men, one became a teacher, one the local sexton, one an editor.

My father, still another Will Borland, was the editor. He started to learn the blacksmiths trade, but after a year of it he walked out of the shop and apprenticed himself to the village printer. He became a master printer and, eventually, a part owner of the weekly newspaper where he had learned his trade. But he, too, had the westward urge and dream of his father and his fathers father. So we went to Colorado, that spring of 1910, and settled on a homestead almost thirty miles south of the Platte valley town of Brush.

By 1910, railroad promotion and the depression of 1907 had persuaded a good many marginal farmers in the Midwest that free land, even on the forbidding high plains, was worth a gamble. They were willing to bet Uncle Sam, as the saying went, that they could live on those dry plains five yearslater reduced to threewithout starving out. If they won the bet, the land was theirs. If they lost, all they lost was their time and a little labor. So there was a fringe of homestead settlement all around that arid area when we arrived. My father chose a homestead out beyond that fringe.

Our homestead was as far from Brush, both in distance and in travel time, as Hillsdale, Ohio, had been from Chillicothe in my great-grandfathers day. It was as far as my grandfathers homestead near Vesta, Nebraska, had been from Nebraska City. In terms of horse travel, the means they used and the means we used, it was a good five hours each way even in good weather. In spring mud or winter snow it was a long all-day trip each way. There were telephones in our day, but the nearest one was twelve miles from the homestead. So was the nearest post office. The nearest doctor was thirty miles from us. And our closest neighbor was two miles away.

Looking back from this age of atomic power, our life on the homestead seems almost as strange as life in Medieval England. Yet the grandfathers would have been at home there. They pioneered in timbered country, but the plains would not have baffled them for long. Lacking logs, they would have built a sod house, as we did. Lacking firewood, they would have burned cow dung and sheep dung, as we did. They would have made do with what they had until they could provide better. They would have hunted their own meat, ground their own corn, tended their own sick, buried their own dead, and persisted. And all without heroics; with only that dogged determination, that persistence in the dream, which is a bright golden thread through all of Americas history.