More Amazing Tales from Indiana More

Amazing

Tales

from

Indiana

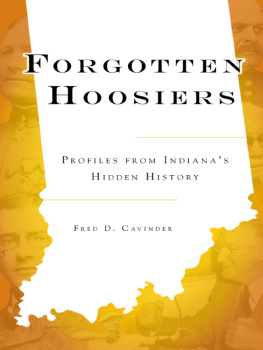

Fred D. Cavinder

Except where noted, all photographs

have been provided by Fred Cavinder.

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA

http://iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail iuporder@indiana.edu

2003 by Fred D. Cavinder

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cavinder, Fred D., date

More amazing tales from Indiana / Fred D. Cavinder.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-253-21653-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. IndianaHistoryAnecdotes. 2. IndianaMiscellanea.

3. Curiosities and wondersIndiana. I. Title.

F526.6.C38 2003

977.2dc21

2003009551

1 2 3 4 5 08 07 06 05 04 03

To Wanda,

whose

amazing

support

makes

it all

worthwhile.

Contents

W hen I wrote an earlier book on oddities in Indiana, the phrase Will wonders never cease? was used. It was an expression common in earlier times, usually spoken with some scorn, not so much to suggest disbelief as to indicate that the expected had occurred and that any announcement of it was merely a firm grasp on the obvious. However, in the book in question, Amazing Tales from Indiana, it was used as a jumping-off place to illustrate that there were so many wonders in Indiana that you could take your pick.

The editor wondered aloud whether wonders really are ceaseless in Indiana or whether I was merely using hyperbole. This book is something of an answer to his question. The short answer is that Indiana wonders never cease. The longer answer is that Indiana has a surfeit of wonders, both great and small. Those which are small become more suited to trivia than to a collection of anecdotes.

So, aside from the research involved, collecting amazing Hoosier tales is an exercise similar to what must be employed by a circus impresario. He knows that a trained elephant is a wonder to many, but a two-headed man is a greater attraction to most.

Clearly there is an almost inexhaustible supply of amazing tales, and they continue to accumulate with each passing year. In some cases the possibility of wonder exists, but history has deprived us of details. Herb Shriner said he came to Indiana as soon as I heard about it/There may be an amazing tale behind that, as well as the clear humor that Shriner intended. But, although Shriner named his daughter Indiana, there seems little likelihood of unearthing a wonder in his adoption of the state.

The disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa, head of the Teamsters Union, like his birth in Plainfield and his rise to fame, is an amazing story in itself. But without details of what happened to him, it remains mere speculation. Similarly, Ambrose Bierce, who began his career in Indiana, is a man who disappeared in Mexico, leaving everyone wondering about his last days.

Eugene V. Debs of Terre Haute provides an enthralling subject for biography, but once one has said that he ran for president from federal prison, the wonder vanishes, mistlike, through lack of startling details. Nor can one dredge up much fascination about Sandy Allen of Shelbyville, at seven feet the tallest woman in the world, at least not without burrowing into her private life.

In Evansville, it is written that on October 19, 1961, a rainy day, eight diapers were hung out to dry. They caught fire. The incident has been blamed by some on the supernatural, but without some kind of definitive explanation, it all seems a bit more whimsical than wondrous. Had they been on babies at the time, it might have sharpened the tale.

Some stories have not yet developed to the point of amazement. On farmland near Plymouth, it is said that a farmer buried a meteorite that fell in 1872. He had become weary of continually striking it with his plow. But nobody knows for sure where the meteorite is located, although recently a meteorite hunter from Ohio vowed to find the item. To collectors it would be valuable and amazing, considering it is said to be four feet by three feet in size. Time will tell, but its mere speculation so far.

By the time this book appears, we all may know whether the relentless, pulsating humming noises heard by some at Kokomo and causing maladies are amazing or only mundanealbeit a bit unusualsounds from explainable sources. Sometimes the passage of time turns something extraordinary into merely the ordinary.

Clearly, although wonders never cease in Indiana, unearthing them is like sifting sand. They often turn on a fine point, and they can be elusive. Their worth rests on being assessed by Hoosiers both skeptical and well aware of how ceaselessly wondrous a state it is.

More Amazing Tales from IndianaAsk most people what the Indiana dunes were like in the late 1700s, and most would imagine an empty wastelanda logical and fairly accurate assumption. Yet the dunes were the site of a battle during the Revolutionary War. It was a minor skirmish but one that caused loss of life and changes in war strategy. It became known as the Battle of the Dunes or the Battle of Trail Creek.

In December 1780, after George Rogers Clark had seized Vin-cennes, the British controlled Fort St. Joseph far to the north, near what is now Niles, Michigan. It was an old trading post established by Catholic missionaries and fur traders in the 1600s. One of its chief functions remained trading with the Potawatomi Indians, and bales of valuable furs were stored there by nearby villages.

About thirty Americans and Creoles from Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and other French settlements marched to Fort St. Joseph. They had little trouble seizing the post, which did not maintain a regular garrison. Knowing they could not hold the fort, the invaders fled with the furs, chased by Indians allied with the British and probably led by Chief Anaquiba and his son, Topenebee, from a large Potawatomi village south of the fort.

The two forces met in a running fight December 5, 1780, along the trail in what are now LaPorte and Porter Counties. Only three invaders escaped. Seven were taken prisoner. The rest were killed. The furs were recovered at a spot called the Petite Fort in what is now Dunes State Park.

The battle was small. The motive for it may have been to divert attention from other French American movements, but that was obscured by the lure of the furs. Nevertheless, historians feel that the fight, of which little is known and even less written, raised British prestige in the area and slowed American plans to capture Detroit, a stronghold vital to control of the Northwest Territory.