First published 2006 by Paradigm Publishers

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2006, Taylor & Francis except Chapter 11, Bringing Obligations Back into Human Rights, copyright 2006 by Irving Louis Horowitz

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Trevio, A. Javier.

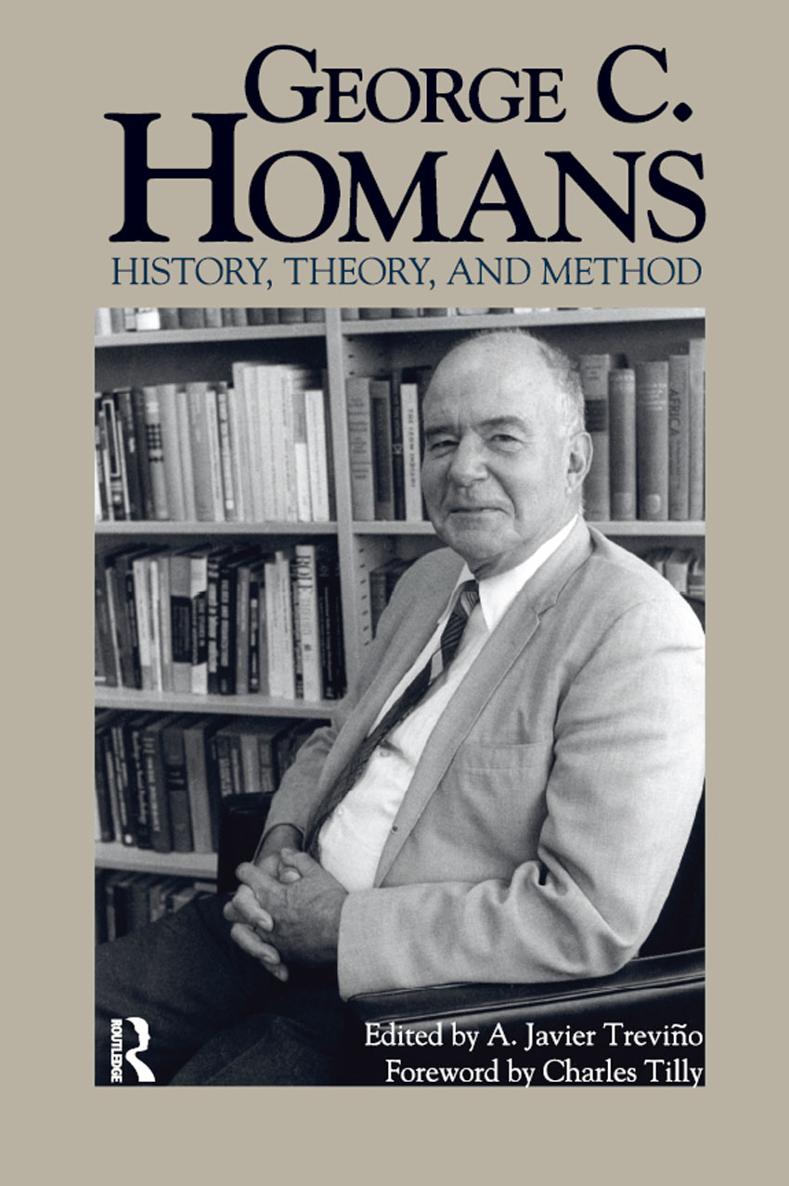

George C. Homans: history, theory, and method / edited by A. Javier Trevio; foreword by Charles Tilly.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59451-191-2 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-59451-192-9 (pbk)

1. Homans, George Caspar, 1910 2. Sociology. I. Trevio, A. Javier, 1958

HM479.H65G46 2006

301.092dc22

2006001603

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-191-2 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-192-9 (pbk)

Charles Tilly

What a vivid pleasure to recall George Caspar Homans! My first memory of him runs back almost sixty years. George stood, ramrod straight, before an undergraduate class in Harvards Emerson Hall. With zest, he told us youngsters about the Bank Wiring Observation Room, the Norton Street Gang, the family in Tikopia, Hilltown, the Electrical Equipment Company, and human social life at large. Unlike his fellow teachers, Pitirim A. Sorokin and Talcott Parsons, Homans spoke to undergraduates with radio announcer articulation and force, daring his listeners to doubt what he said. His Boston Brahmin accent reinforced the sense that any challenge had better be clear, sensible, and brief. Yet we knew that he would listen, think, and reply cogently.

At that stage (already past English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century and en route to The Human Group, which packaged, between hard covers, the undergraduate lectures we heard), George presented himself to undergraduates as a hardheaded empiricist, impatient with fluffy concepts and unverifiable explanations. Only later, as he was working toward Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms, did he begin to distinguish between the empirical generalizations that preoccupied him in The Human Group and the explanations he hoped to deduce from more general propositions about, yes, human social behavior.

Many authors in this book analyze what George meant by that distinction and how well he deployed it. Their perceptive work frees me from having to describe, explain, and criticize what he was doing. Still, it is worth noticing to what a large extent George undertook his later writing as an effort to cleanse sociologys Augean Stables of their accumulated dross. As the introduction to Social Behavior, explicitly footnoting his colleague and friend Talcott Parsons, put the point:

Much modern sociological theory seems to me to possess every virtue except that of explaining anything. Part of the trouble is that much of it consists of systems of categories, or pigeonholes, into which the theorist fits different aspects of social behavior. No science can proceed without its system of categories, or conceptual scheme, but this in itself is not enough to give it explanatory power. A conceptual scheme is not a theory. The science also needs a set of general propositions about the relations between the categories, for without such propositions explanation is impossible. No explanation without propositions! But much modern sociological theory seems quite satisfied with itself when it has set up its conceptual scheme. The theorist shoves different aspects of behavior into his pigeonholes, cries Ah-ha! and stops. He has written the dictionary of a language that has no sentences. He would have done better to start with the sentences. (Homans 1961: 1011)

The passage combines exasperation with missionary zeal.

Yet it also conveys a false impression of a true believer. It took me years as Georges student and then as his colleague to recognize two features of his bombastic intellectual style. First, he actually welcomed challenges. He enjoyed arguing more than sermonizing, esteemed serious opponents, and refused simply to tuck an objection into some unused corner of his analytical scheme. Second, for all his stridency, he despised sham, including any possibility of sham in his self-presentation.

One personal story sticks in my mind. In May 1976, Georges Harvard colleagues organized a day of talking and feasting to celebrate his retirement. They recruited me as one of the outside speakers. My talk intertwined an appreciation of Georges historical work with takes from his poetry and several references to his favorite painter J.M.W. Turner. Years before, George had explained to me that Turner had invented impressionism long before any French painters thought of it. An impressive Turner hung in his dining room.

Shortly after my talk, as it happened, George and I were seated side by side at lunch. He turned to me and said, Charlie, I noticed that you talked about Turner. I pointed out that he had told me about his admiration for Turners work, and that no one could forget the Turner he had in his house. Charlie, he roared with delight, Its a fake! He explained what had happened. His sister had received the alleged Turner as part payment of a debt due her by an art dealer, then had given it to George, who hung it on his wall. A few years before the retirement ceremony (as fallible memory recalls it), the sister had visited the Turner collection at Londons Tate, boasted of the family Turner, and intrigued the Tate curator. When the curator next came to Boston, he visited Georges house, inspected the painting carefully, and pronounced it a very good copy.

So what do you have up there now? I naively asked George. Its still there, answered George, laughing. We liked it before, and we still like it. That was George, confident enough in his own lineage, talent, and accomplishments that he had no use for sham.

Readers of this book will soon learn that for all the subsequent work challenging, refining, and extending George Homanss intellectual contributions, his original writings still deserve attention today. They deserve attention for their energy, clarity, and spirit of adventure. Perhaps what sociologists now call exchange theory will stand as his most durable heritage. Perhaps others will recognize that, contrary to his reputation as a radical psychological reductionist, from early on George located his crucial causes and effects of social behavior in interpersonal transactions rather than individual minds. Perhaps his analyses will come into their own again now that behavioral economics and a wide variety of relational analyses are flourishing as alternatives to the rational choice foundations George self-consciously rejected when it came to microfoundations for social science.