The New York Times

BOOK OF

WINE

MORE THAN 30 YEARS

OF VINTAGE WRITING

Edited by HOWARD G. GOLDBERG

Foreword by ERIC ASIMOV

STERLING EPICURE is a trademark of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. The distinctive Sterling logo is a registered trademark of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

2012 by The New York Times. All rights reserved.

All Material in this book was first published in The New York Times and is copyright The New York Times. All rights reserved. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of the material without express written permission is prohibited.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4027-8184-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4027-9381-3 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The New York Times book of wine / edited by Howard G. Goldberg.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-4027-8184-1 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-4027-9381-3 (ebook) 1. Wine and wine making. 2. Food and wine pairing. I. Goldberg, Howard G. II. New York times. III. Title: Book of wine.

TP548.N49 2012

641.2'2dc23

2011052425

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

www.sterlingpublishing.com

B ack in 1972, Abe Rosenthal, then the managing editor of The New York Times, assigned Frank J. Prial, a city reporter, to write a weekly column on wine. It would be the first regular coverage of wine in a general-interest American newspaper, though nobody was certain a desire for such reporting actually existed.

Well try it for a couple of months, Prial recalled Rosenthal saying.

A couple of months turned into 40 years and counting, and the scope of wine coverage has grown immensely. What started as a sideline for Prial, who crammed his wine writing into moments spared from his general assignment duties, evolved into a full-time job. He, along with other writers and correspondents, traveled the world, visiting wine regions ancient and new, reporting on personalities and politics, economics and conflict, issues, trends and, of course, the liquid in the bottle that was the source of it all.

The story of wine is as old as recorded history. Looking back to its ancient origins, 40 years may not seem like such a long time. Yet in those scant few decades Americans have achieved an entirely new and different understanding of wine. When Prial began writing his Wine Talk column, Americans bought what little wine they drank largely in jugs. Many of these jug wines were assigned names that connoted the Old WorldChablis, Chianti, Rhine Wine, Hearty Burgundybecause, after all, wine was thought to be European in nature. Indeed, many of Californias historic vineyards had been planted by European immigrants who were not about to let thousands of miles stand between them and their daily beverage.

Back then, the California wine regions that today are among the most prestigious in the world were hardly known. Napa Valley had barely begun its ascent to glittering stardom. The Russian River Valley was apple country. Glossy magazines had not yet begun to exalt wine as an essential element of the good life. Robert M. Parker Jr. had not yet introduced the 100-point scale that would give consumers an easy-to-understand tool for making buying decisions. The few scattered American wine connoisseurs of the time looked to Bordeaux as the epitome of fine wine, Burgundy to a lesser degree, and, of course, Champagne, which, if one knew nothing else about wine, one at least understood that Champagne was the beverage of celebrations.

Oh, how the world of wine has evolved since then. The United States is now the worlds largest consumer of wine. While it cannot rightly be called a wine-drinking countrya surprisingly small percentage of the American population accounts for an inordinately large percentage of the wine consumedthe United States now has a thriving wine culture, several distinct ones, in fact.

These 40 years have seen not only a revolution in the American perception of wine, but sweeping changes the world over. For centuries the vast amount of wine produced in Europe was sold locally, to nearby villages and occasionally to a city up the river. Now, grape varieties that few people knew existed 40 years agosavagnin, nerello mascalese, menca, grner veltlinerare sold globally, and in good wine shops the nation over.

Thirst for the benchmark wines, like first-growth Bordeaux and grand cru Burgundy, has risen exponentially, as, of course, have prices. No longer will a generation of wine lovers, like Prials, be able to hone their understanding on fine old Bordeaux and well-aged Burgundy, not when these older bottles are auctioned off for thousands of dollars apiece and the Chinese are paying equivalent amounts for the most recent vintages.

Yet wine lovers coming of age in the 21st century have a wealth of choices that were undreamed of 40 years ago. American stores are jammed with great alternatives to the benchmark wines from all over Italy and Spain, France and Germany. Portugal is coming on strong, as are Austria and Greece. Eastern Europe is playing catch-up, but the fall of the Iron Curtain has allowed ancient wine cultures in Hungary and Georgia, Slovenia and Croatia, to begin the long process of rejuvenation.

What of the United States and other New World wine regions? Napa Valley led the American charge away from jug wines, culminating in the cult cabernets, expensive status bottles that were a world away from the jugs but had less to do with the joy of wine drinking than the jugs did. Still, great wine now comes from California and Oregon, Washington and New York State, with high hopes for areas in between, like Michigan and New Mexico. Australia and New Zealand have changed the way the world buys wine, while Argentina and Chile have become important sources of good, inexpensive wine, and can produce far better. South Africa and Uruguay have leapt into the global wine business. Can China, India and Brazil be far behind?

The articles in this anthology tell the story of this revolution in wine, sometimes in close-ups, and other times in sweeping panoramas. The storytelling has evolved as well. Earlier on, readers required plenty of introductory information, spoon-fed in digestible doses. Now, Americans are far more knowledgeable about wine, even as many people remain far from comfortable with it.

Wine is now a significant component of American culture, to be evaluated, analyzed and parsed just as with other cultural expressions, whether restaurants, architecture, pop music or films. What was once an additional beat for Frank Prial to try for a couple of months is now a field firmly established at The New York Times, 40 years and counting, with its own full-fledged critic. This anthology chronicles wines coming of age in the United States, from an American point of view. Weve been through childhood innocence and adolescent hiccups, and if we have not yet reached confident adulthood, we seem to be heading there.

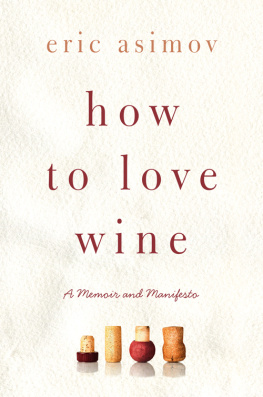

Eric Asimov

Next page