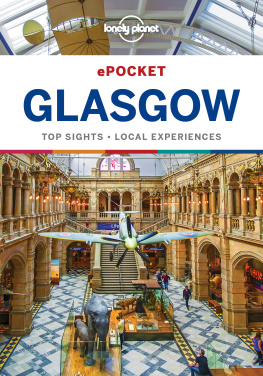

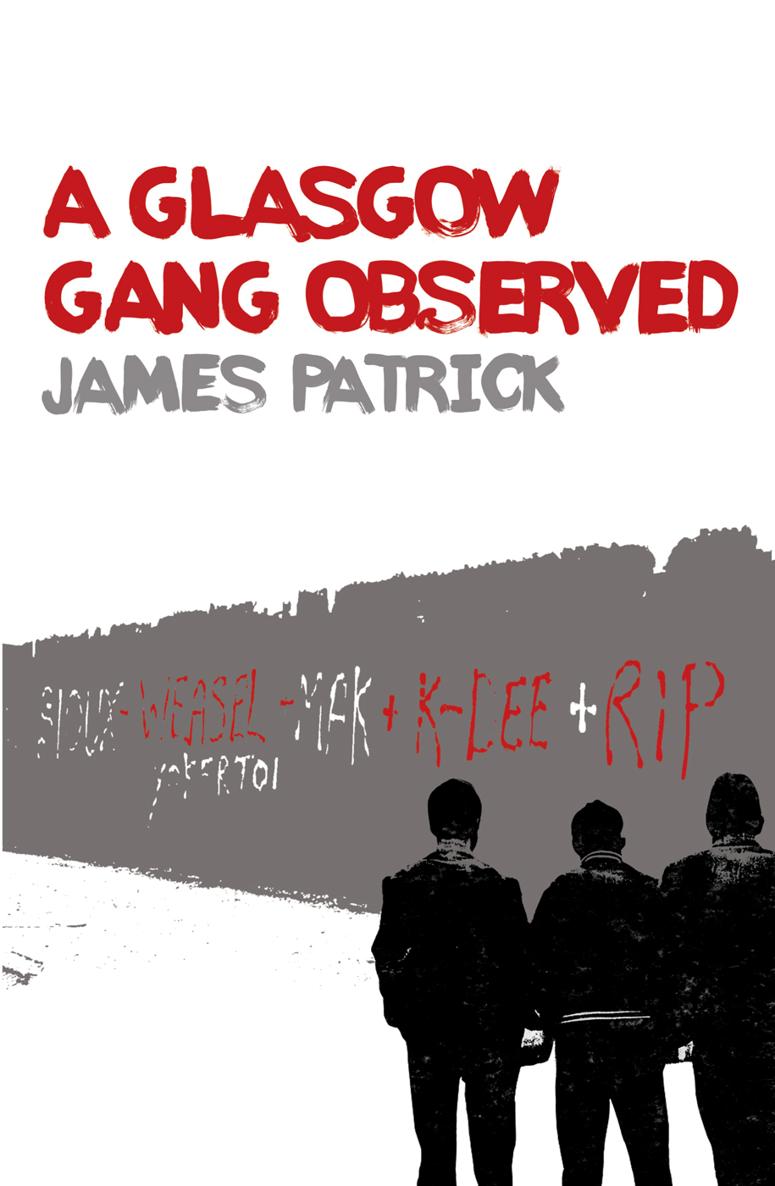

James Patrick wrote his book in the late 1960s but so much of it seems to speak to today and our growing worries about gang violence. In his book there is a map of Glasgows gang territories. A similar one exists today. The territories sit neatly within the poorest areas. Patrick is a pseudonym chosen by the author who was, when he researched the book, a teacher in an approved school. He befriended a pupil called Tim and, with the boys connivance, accompanied him on his weekends out and joined the young mans gang. Tim was effortlessly well-behaved throughout the week at school. He was just above average intelligence and likeable. In deciding to open his teachers eyes to gang life, he understood the risks far more clearly than the author did.

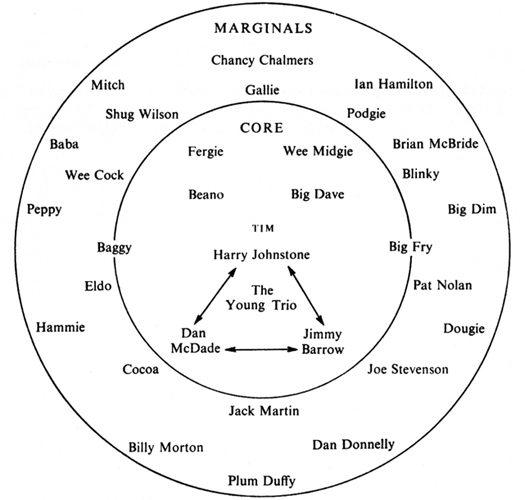

Initially, Patrick found himself accepted into a loose association of youngsters who spent their days hanging around street corners and their evenings in pubs and dance halls. Most of the time they told stories, or stared into space. Then, in a finger snap, violence could erupt. On his first evening, a man accidentally brushed against a gang member in the pub. He was bashed over the head with a glass bottle. He and his mate were then dragged to the floor where they were jumped on and kicked in the head. On this, as on all occasions, all gang members joined in. I was reminded of a pride of lions or pack of wild dogs, springing into action at the prospect of a threat or a kill.

The boys, for thats all they were, would send out challenges to enemy gangs and, mob-handed, do battle, fuelled by fear and aggression. Once the fight started they expected no mercy and gave none. Tim, so temperate throughout the week, demonstrated his leadership skills with hammer, club or blade.

In a matter of weeks the situation had become too hot for Patrick to handle but, during his time with the gang, he gleaned valuable information. Tim, for example, inherited his role from older brothers who had gone on to greater violence and were thus feared and respected. His father encouraged his participation and his mother ignored it. The gang offered Tim, and his contemporaries, a life. Outside it they were poor, uneducated nobodies. In the gang they had station and respect. Approved school, borstal and prison were regarded as unfortunate side-effects.

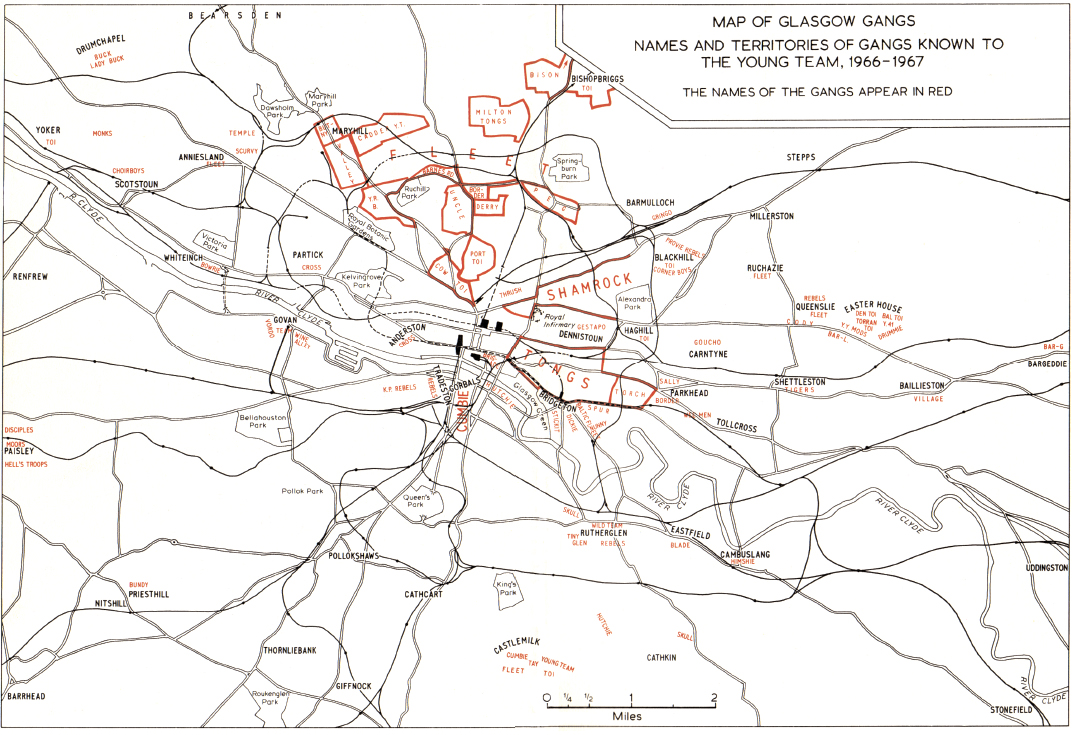

I might have put A Glasgow Gang Observed back on the bookshelf in the history section for some of the gangs mentioned date back to the 1880s. However, a series of articles in the Evening Times in 2006 convinced me little had changed. Reporter David Leask witnessed gang warfare and discovered the gangs made appointments to fight. Weapons included golf clubs, metal poles, razors and knives. And gang membership still restricts its members to their own territory. When Leask told an unemployed Ruchazie youth there were jobs at Glasgow Fort, the boy looked horrified. He said: I would have to get a number 38 bus and that goes through Garthamlock. There is no way Im going to risk my life like that.

However, to those growing up in these areas, the advantages of gang membership outweigh the disadvantages. In fact, for the youth who is growing up without a stable family or much education, arguably it is an intelligent decision. It offers protection, companionship, acceptance, status, a peer group and purpose. That is what our side of the parallel universe has to understand. That is what we have to counter.

Collette Douglas Home, The Herald, 4 September, 2007

Neil Wilson Publishing Glasgow

to the boys of

who never say no

Contents

Preface to 1973 edition

THIS BOOK HAS been written for the general reader rather than for the criminologist, the clinical psychologist, or the specialist in the sociology of deviance, because I believe the problem described is of more than academic importance. It does not purport to be an authoritative or exhaustive treatise on Glasgows juvenile gangs, but is a descriptive account of a participant observation study of one such gang which I met on 12 occasions between October 1966 and January 1967.

In all I spent just under 120 hours in the field; and as my involvement with the gang deepened, so the hours lengthened until towards the end of January I was in the company of the gang during one weekend from seven oclock on Friday evening until six on Sunday morning.

I have deliberately allowed some years to pass between the completion of the fieldwork and publication. The main reasons for the delay have been my interest in self-preservation, my desire to protect the members of the gang, and my fear of exacerbating the gang situation in Glasgow which was receiving nationwide attention in 1968 and 1969. Reasons of personal safety also dictate the use of a pseudonym.

What follows is not a study of Glasgow, or of Glasgow youth in general, or of a particular community within the city. It is a small-scale piece of research which is in no way a statistical survey and so the conclusions may well be of a restricted character. My aim has been unashamedly exploratory to present a brief glimpse of the reality which engages Glasgow gang boys, to comprehend and to illuminate their view and to interpret the world as it appears to them. (Cf. Matza, 1969, p.25)

I have not been able to include for legal reasons a full account of my relationships with the gang or with the police. As a result, a discussion of the ethical and methodological problems associated with participant observation has been postponed to such time as a complete record of events can be given.

It remains for me to acknowledge my indebtedness to a variety of people, especially James McMeekin and Max Paterson for professional and personal advice. Stan Cohen and David Downes kindly read the more analytical chapters which were improved by their suggestions. I should also like to thank Charles McKay and Leonard Turpie for the various forms of help they gave me.

James Patrick, August, 1972

Acknowledgement

The lyrics to Deadend Street by Ray Davies which appear on pages are Warner/Chappell Music, Inc., Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, Universal Music Publishing Group.

The Young Team, 1966-7

Preface to 2013 edition

THIS BOOK BEGAN life as a thesis for the University of Glasgow, although not one which initially it was keen to accept. As I explain in the text, I was originally invited to join the gang by Tim Malloy, the pseudonym I gave to a boy in an Approved School where I was working as a newly qualified teacher. I wanted to understand why boys on leave from the school for a weekend, instead of demonstrating their ability to keep on the right side of the law, often returned to the school with further serious charges against them which increased their period of detention. Tim, for his part, was just as keen to show me that I, as a young, middle-class Glaswegian who had been brought up only a mile from him, might as well have come from the moon, so little did I understand his life.

In addition to working in the Approved School, I was simultaneously studying for a higher degree and began casting around for a suitable subject for a thesis. So when the tutor gave each student in the class a 5x3-inch index card on which to commit our first thoughts on the title and topic of our proposed theses, I wrote: A participant observation study of a Glasgow gang. Three years later I submitted my thesis, having not heard from my supervisor in the meantime: thats what passed for higher degree supervision in those days, although I did receive useful advice from other members of staff when I was preparing the text for publication.