2021 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

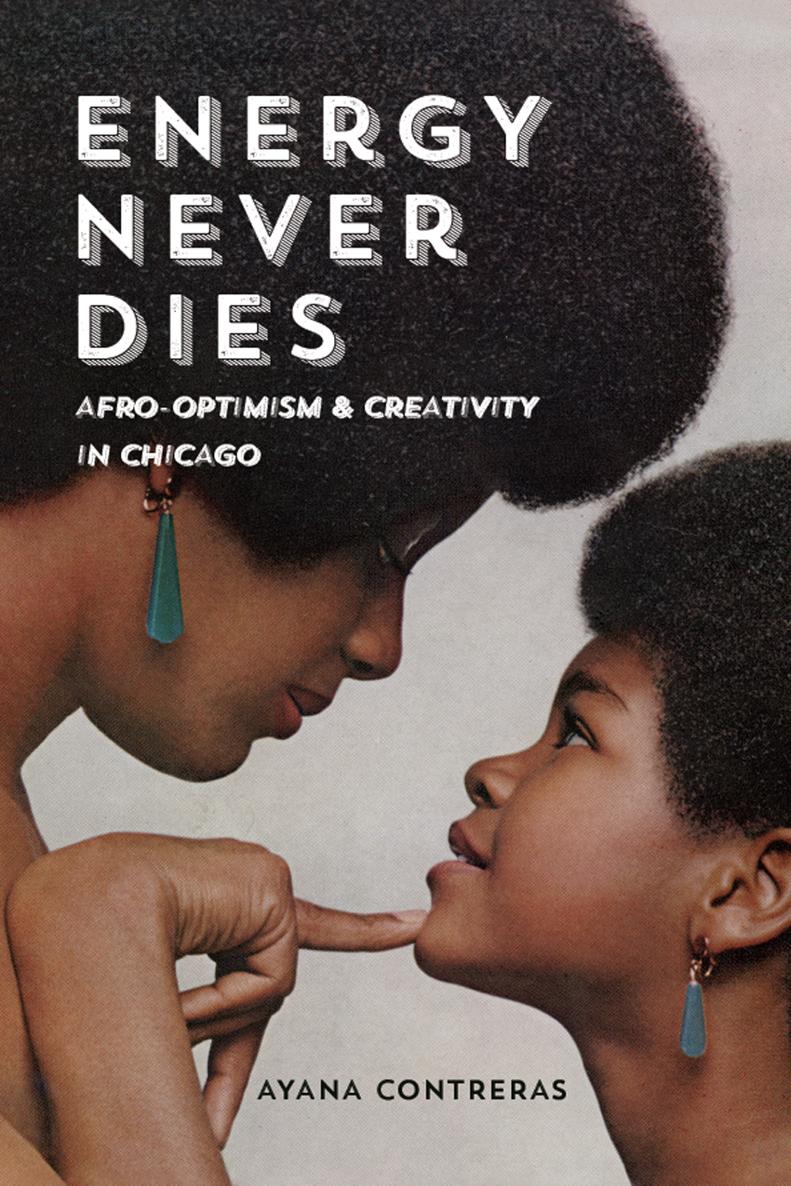

Names: Contreras, Ayana, 1981 author.

Title: Energy never dies : Afro-optimism and creativity in Chicago / Ayana Contreras.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021035774 (print) | LCCN 2021035775 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252044069 (cloth) | ISBN 9780252086113 (paperback) | ISBN 9780252053009 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansIllinoisChicagoMusic History and criticism. | Popular musicIllinoisChicago MusicHistory and criticism. | African Americans IllinoisChicagoSocial life and customs. | African AmericansIllinoisChicagoAttitudes.

Classification: LCC ML3479 .C64 2021 (print) | LCC ML3479 (ebook) | DDC 780.8996073/11dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021035774

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021035775

This book is dedicated to my grandmother Phyllis, who believed in me, to all of the wonderful folks whove been so generous with their stories, their old record albums, and their time, and most of all to the Black Chicagoans of our past who had the audacity to believe our future could be brighter than even they could imagine.

preface

the verge of spring

optimism in black chicago

If you really want to be free, you have to take charge of your capacity to shape the world.

Kerry James Marshall

I am preoccupied with stories. Not fairy tales, not imaginings, but real-life stories that give me hope in the improbable. It just happens to be that Black Chicago is a place steeped in those stories. Unfortunately, much of todays media about Black Chicago paints the community as a soulless, lawless place where brother is pitted against brother. Those stories zoom in on the few. The many are rendered silent. Bit players in their own movie.

If you are not from here, some stories might be unknown to you; but to explain the meaning of Taurus Flavors or Curtis Mayfield in a line or two would do a disservice to all of us.

I believe that Black Chicago has a unique culture, rooted in self-determination, creativity, optimism, and hustle. Its passed down through our music and media, replicated over and over. And that music and media has been disseminated throughout the world, via Haki Madhubutis Third World Press, Ebony and Jet magazines, the work of Lerone Bennett Jr., Curtom, Chess, and Brunswick Records, and even through Afro Sheen advertisements on Soul Train. And thats the short list.

Curator Leslie Guy (a Philadelphia native who at one time worked at Chicagos DuSable Museum of African American History) once told me that Black Chicago feels like it is always on the verge of spring, as though that big breakthrough, that metaphoric flush of sunshine, is always just around the corner.

I argue that part of that feeling is due to our trait of clinging fast to our faith. Baked into the culture of Black Chicago is the belief that the improbable can happen, perhaps against the odds, because there are so many tales of these things happening right before our eyes. In the world of visual art, you neednt look further than the intergalactic career arc of Kerry James Marshall or the equally lofty launch of artist and urban planner Theaster Gates, both Chicagoans. Marshall has called Chicago home for decades, and Gates was born and raised in Chicago. Their success stories alone have brought innumerable members of the creative class to Chicago. But the part of those oft-cited fairy tales that is often left out is how long each of them toiled on the edge of winter before their breakthrough to their spring. Each of them are incredibly willful souls, and part of their successes lie within their shared belief that they can craft their own narrative.

I choose to pepper this text with the term Afro-optimism to describe this phenomenon, primarily as an antithesis to Afro-pessimism: a concept to which I have a visceral reaction each time I encounter it.

Usually traced back to Orlando Pattersons 1982 book, Slavery and Social Death, the concept of Afro-pessimism identifies slavery as the perpetual state of being for Black America. That we are, in essence, doomed as a consequence of birth.

As recently as 2020, Frank B. Wilderson III argued a version of this notion in his book Afropessimism. For Wilderson, the state of slavery, for Black people, is permanent, Vinson Cunningham explains. He continues: every Black person is always a slave and, therefore, a perpetual corpse, buried beneath the world and stinking it up.

This lens speaks so ardently to the scars, the trauma of slavery, but in my estimation it also does a disservice to those who literally passed through the nadir so that we might come out the other side. And lets say, for arguments sake, that the vestiges of slavery in fact forms the basis of Black American culture. Does that imply that the frame of self-defeatism, of never-ending tailspin, is an imperative of viewing Blackness?

Its noteworthy to me that Wildersons book Afropessimism folds vignettes of his life into the argument. Looking at the plain facts of his upbringing and accomplishments (his father was a professor, Wilderson earned a bachelors degree from Dartmouth College, a masters from Columbia University, and a PhD from UC Berkeley, and Wilderson III is an accomplished dramatist, writer, and educator in his own right): his life could just as easily be framed as a tome on Afro-optimism. That is to say that despite being constantly Otherized and ostracized, he has crafted a life to be proud of. But he chooses to concentrate on the factors (systemic and otherwise) that hang as a specter over himlets call them the external facts of Blackness. I dont suggest in Energy Never Dies that these external facts of Blackness dont exist, or should be addressed and accounted for, I suggest that they cannot extinguish the wonderous stuff we are made of: the internal facts of Blackness.

To me, this lens of Afro-pessimism (as expressed by Wilderson and many others) quite literally counters the lifeblood, the very DNA of Black Chicago culture. If the Johnsons had not believed in the notion of a Black version of Life magazine, Ebony magazine would have never existed. Black Chicago is defined by self-determination and by the belief in the improbable. We believe that, despite reports to the contrary, we are not yet dead, but perhaps as curator Leslie Guy surmised, we are on the verge of spring. If our Black American ancestors had not believed in the possibility of a better tomorrow (in order to just keep living), I shudder to think of what the world would have missed out on. Self-defeatism is easy to get sucked up into, but belief in an alternate reality is the escape hatch (if only in our own minds).

In an unpublished essay written during a 2007 visit to Chicago, philosopher, poet, and theorist Fred Moten writes: