About the book

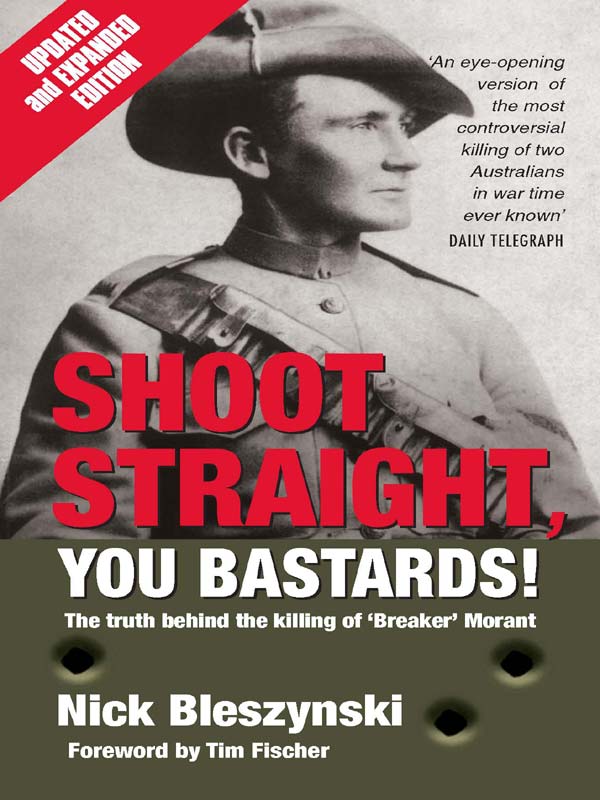

The question of The Breakers innocence is still being fiercely debated more than a century after Lieutenant Harry Morant and Lieutenant Peter Handcock were shot on a lonely veldt outside Pretoria at dawn on 27 February, 1902, by a British military firing squad.

Shoot Straight, You Bastards! is a universal account of greed, ambition and the power of the political machine that crushes anyone who gets in the way. In much the same way that Bruce Beresfords award-winning feature film Breaker Morant captured the popular imagination, Shoot Straight, You Bastards! is an explosive read as controversial an event today as it was 101 years ago.

In every war there is a character like Morant - a rebellious spirit who ends up on the wrong side of the great cause. This updated edition includes an appendix containing dramatic new evidence that Kitchener gave orders to take no prisoners. Expert legal opinion supporting the Breakers innocence and a strong campaign to secure a proper judicial review combine here in a story Australians have waited more than a century to read!

A brave race can forget the victims of the field of battle, but never those of the scaffold. The making of political martyrs is the last sanity of statesmanship.

Foreword

There was some significant opposition to Australias participation in the Boer War or to be more precise, the participation of various detachments from the State colonies as Federation had not been formed when the first troops went to South Africa.

However the opposition, whilst publicly stated, was not sufficient to deter Breaker Morant and Peter Handcock from entering forth into fierce battle in the area north of Pretoria, culminating in the capture of several Boer prisoners and the killing of the German missionary Heese.

This story is one of detail with regard to these aspects of the Boer War, which in turn led to a trumped up court martial, a conviction of guilty and subsequently the execution of two brave Australians on a clear blue morning, thousands of kilometres from their homes, in February 1902.

There is no doubt this book is about a hundred years too late, but it is certainly a case of better late than never. A magnificent writing involving comprehensive research relating to one of Australias greatest military controversies, the author has left no stone unturned in getting to the bottom of what exactly happened, especially with the conduct of the court martial.

The Boer War was not just some form of African Dutch rebellion against the British Commonwealth Forces and governmental administration. It was something much deeper than that and it is doubtful, all things considered, whether Australia had a particular role to play militarily even before the nation of Australia had been officially formed.

There were some extraordinary leaders on both sides of the Boer War, such as Horatio H Kitchener, known as Lord Kitchener, a man not courageous enough to stay at post in Pretoria on the day of the executions of Breaker Morant and Peter Handcock. On the other side there were leaders like General JC Smuts who went on to become a great builder of the modern South African nation and in an extraordinary twist of events was, as a Senior Minister of the National War Cabinet during World War II, for a brief period Acting Prime Minister of Great Britain.

There are two particular reasons why Australians and people beyond Australia should follow with interest this exciting story. On the one hand, this was the first war in which the media played an important and huge role. Helped by the activities of crisp and colourful writers such as Winston Churchill, along with the advent of the telegram, battles were covered in some considerable detail back at home. Indeed, upon the news of the release of Mafeking after a 217-day long siege by the Boers, there were celebrations right around the Commonwealth in a matter of hours thanks to the telegram and journalists being on hand.

The point should be made that this media coverage was a double-edged sword. The British Government and Kitchener were under pressure, generated by the media, to see that there was adequate punishment dished out to those Commonwealth troops who went beyond the bounds in the conduct of this bitter war. It could be said from a careful reading of this excellent book, that it was the advent of detailed media coverage that led to Kitchener needing scapegoats and two Australians being designated as those scapegoats. The evidence is there that Kitchener wanted a hanging court martial and nothing too much should be allowed to interfere with that result.

The second overall element is one for Australia alone, and that is how two of our citizens could have been slaughtered or shot dead on the altar of political expediency of a military flavour. One hundred years on, this must represent unfinished business, and as much for ensuring proper precedent as anything else, Australia and the Australian Government should take steps to render a Measure of Honour for these two iconic soldiers.

Guerrilla war and the war against terrorism, in an extraordinary parallel, are once again unfolding upon the world a century after the Boer War. It is essential that honour be restored to Morant and Handcock, because they did not deserve to die as a consequence of a curious court martial. Also, it should be a reminder that Australians under the command of British, United States, Thai and other international force leaders, are still deserving of vigorous support by the Australian Government, and overarching scrutiny of any disciplinary action taken against them.

This book represents a mighty step forward in the right direction. But whilst various people may reach different views as to who actually killed whom and why, even if Breaker Morant killed Boer War prisoners in cold blood, even if Peter Handcock dealt with and killed Heese, undeniably there were mitigating circumstances whereby at no stage should they have been sentenced to death by firing squad.

Lastly, the book uncovers in detail a third Australian victim, namely Tenterfield solicitor and lawyer JF Thomas. This Australian Army Officer, called on to defend Morant and Handcock at short notice, did a sterling job in all the circumstances but was absolutely destroyed by the verdict and the carrying out of the verdict. In a crucial letter written on the day of the executions, it was already apparent that JF Thomas was going to assume a cross of burden over this matter and carry it to his grave.

It is now well known that he returned to Tenterfield crushed by the outcome of the court martial with a sense that he had personally failed and let down Morant and Handcock. This of course was not the case as he had valiantly defended the two Australians, however his legal practice in Tenterfield gradually declined, he withdrew from the local community and became a hermit suffering from huge bouts of depression. He now rests on a gentle slope in a magnificent setting of the Tenterfield cemetery in far north New South Wales.

At least when I last saw his grave I did not trip over, but when I visited the graves of Morant and Handcock, I stepped back to get a better photo and tripped on the edge of the masonry work and fell heavily to the ground. As I lay in the dust of this strange corner of the Pretoria cemetery, I smiled to myself and thought the Breaker and his mate would be happy enough to know that they still had the ability to bring a measure of authority crashing to the ground.