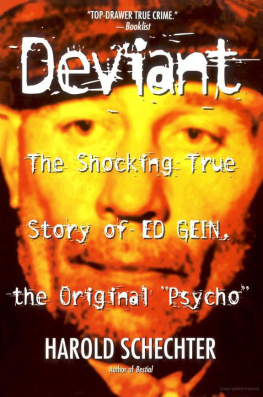

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

H AROLD S CHECHTER is a professor of American literature and culture at Queens College, the City University of New York. He is widely celebrated for both fiction and true-crime writing, including The Devils Gentleman, The Tell-Tale Corpse, and The Serial Killer Files. He lives in Brooklyn and Mattituck, Long Island, with his wife, the poet Kimiko Hahn.

WILLIAM BEADLE,

FAMILY ANNIHILATOR

T HE DIFFERENT ERAS IN OUR NATIONS SOCIAL HISTORY HAVE BEEN DISTINGUISHED not only by their specific fads and fashionsthe kinds of clothes people wore, food they ate, music they listened to, slang they spoke, and so onbut also by the particular criminal types that captured the public imagination: the tommy-gun-toting gangsters of the 1920s, the switchblade-wielding juvenile delinquents of the 1950s, the sex-crazed psycho killers of the 1970s, andin our own post-9/11 agethe suicidal mass murderers, whether school and workplace shooters or apocalyptic terrorists.

During the early years of the Republic, for reasons that historians and sociologists have been at pains to understand, America was gripped by fears of a new kind of killer: the so-called family annihilator, the formerly loving father and husband who, in a sudden fit of homicidal frenzy, hideously slaughtered his children and wife. And of these nightmarish figures, perhaps the most infamous was William Beadle, perpetrator of what one contemporary described as a crime more atrocious and horrible than any ever committed in New England and scarcely exceeded in the history of man.

B ORN IN E NGLAND in 1730, Beadle emigrated to America at the age of thirty-two and eventually settled in the village of Wethersfield, Connecticut, where he operated a country store stocked with an unusually handsome assortment of goods. Surviving documents show him to have been possessed by the sort of overweening egotism typical of family annihilators. Though acknowledging his unprepossessing looks, he regarded himself as far superior to the run of humanity. My person is small and mean to look on, he wrote in one journal entry, and my circumstances were always rather narrow, which were great disadvantages in the world. But I have great reason to think that my soul is above the common mould. In his self-conceit, he likened himself to a diamond among millions of pebbles.

For several years his business thrived. Fiercely proud of his success, he maintained a handsome residence and entertained guests in grand style. He was held in high esteem by his neighbors, who saw him as an honorable tradesman, generous host, loving husband, and doting father.

In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, however, Beadle suffered reversals that left him in dire financial straits. Unable to bear the mortification of being thought poor and dependent, he struggled to keep up the outward appearance of his former affluence. Eventually, however, he succumbed to despair. The thought of being perceived as a failure by his townsmen was more than he could tolerate. If a man, who has once lived well, meant well, and done well, falls by unavoidable accident into poverty and submits to be laughed at, despised, and trampled on by a set of mean wretches as far below him as the moon is below the sun; I say, if such a man submits, he must become meaner than meanness itself.

Concluding that suicide was less shameful than poverty, he decided to kill himself and his family. Like other killers of his psychopathic breed, he justified his intended atrocity as an act of kindness, even love. I mean to close the eyes of six persons through perfect humanity and the most endearing fondness and friendship; for mortal father never felt more of these tender ties than myself. Initially, he thought he might spare his wife. After much deliberation, however, he concluded that it would be cruel to leave her behind to languish out a life in misery and wretchedness. With her entire family suddenly gone, death would be a mercy for her.

As he began to mull over his plan, he kept hoping that Providence would turn up something to prevent it, if the intent were wrong. Instead, every circumstance, from the greatest to the smallest trifle, only served to convince him that destroying his family was the only sensible course. For a while, he prayed that his twelve-year-old son and three little daughters might perish accidentally, thus sparing him the necessity of killing them. To facilitate that end, he removed the protective wooden cover from the backyard well. He also encouraged them to swim in the deepest and most treacherous parts of the nearby river. When the children stubbornly survived these perils, he resolved to take more direct action.

Though uncertain at first as to when and how he would accomplish his great affair (as he described the intended massacre), he had no doubt that he would not quail when the time came. How I shall really perform the task I have undertaken I know not till the moment arrives, he wrote in his journal. But I believe I shall perform it as deliberately and as steadily as I would go to supper, or to bed.

He eventually fixed on the eighteenth of November for the execution of his plan. He first procured a noble supper of oysters, that my family and I may eat and drink together, thank God, and then die. He was forced to abandon his plan, however, when the maidwho had been sent off on an errandreturned unexpectedly and prevented him for that time.

A few weeks later, he made another aborted attempt that he described in his journal:

On the morning of the sixth of December, I rose before the sun, felt calm, and left my wife between sleep and wake, went into the room where my infants lay, found them all sound asleep; the means of death were with me, but I had not before determined whether to strike or not, but yet thought it a good opportunity. I stood over them, and asked my God whether it was right or not now to strike; but no answer came: nor I believe ever does to man while on earth. I then examined myself, there was neither fear, trembling, nor horror about me. I then went into a chamber next to that to look at myself in the glass; but I could discover no alteration in my countenanced of feelings: this is true as God reigns, but for further trial I yet postponed it.