Some of the names have been changed to protect privacy.

Foreword

The first fact of serial murder is that these crimes exist most clearly in the mind of the serial killer himself. That was the most important lesson I learned in the course of investigating Ted Bundys initial killings in the northwest.

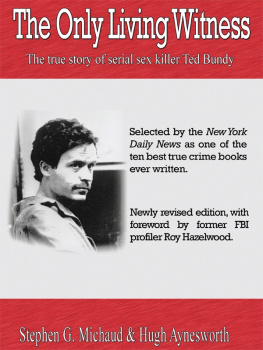

And this is why Ted Bundy: Conversations with a Killer is such a valuable resource.

Few, if any, serial killers have ever talked at such length, and with such clear self-knowledge, as Ted Bundy did with Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth.

Ted was resourceful, intelligent, and relentless; he was forever hunting, always perfecting his approach to his victims. He chose ways to dispose of their bodies with infinite care, and he assiduously studied how police investigations are conducted in order to further reduce his chances of being caught.

Bundy, above all, did not want to be caught, ever.

What is more, for police investigative purposes, his case is prototypical. There is no question that it remains the exemplar of what works, and what does not work, when local law-enforcement agencies are faced with the fact that some unknown subject, almost certainly a male, has begun to periodically murder people, usually women or children.

In Seattle and surrounding King County, we didnt know we had a serial killer until Ted had killed at least eight young women in the region, probably more. The Ted investigations starting point was a summer day in 1974 when a white male subject, seen driving a Volkswagen and calling himself Ted, had apparently lured two women, separately and at different times, from a popular local lake park in broad daylight. All that we knew for certain was that Janice Ott and Denise Naslund had vanished.

It would be two months before parts of their skeletons were discovered on a hillside east of Seattle, and another six months before the severely fractured skulls of four other Bundy victims (all of these women were killed prior to the summer of 1974) were found in a similar wooded location.

The situation for local law enforcement was unprecedented as it is every time a serial killer begins operating and the case immediately presented us with a wide range of unique problems. One was coordination. At least five different and separate police agencies were involved in the early Ted investigation. We were separated from one another by distance it is 265 miles from Corvallis, where Bundy abducted one of his victims, to Seattle and by other features of geography: another coed victim had disappeared from a campus east of the Cascade Mountains, a physical barrier that seemed to preclude, at first, the possibility of a common suspect.

Communications were a related difficulty. Each individual police agency had separate priorities. What was important to one agency was not necessarily important to another. We all used different methods of paperwork. Nor was it practically possible to keep everyone informed at the same time about developments in the case.

These troubles were further aggravated by external factors. Seattle was a frightened, panicked city. Not every politician who spoke out at the time had the sense not to inflame those fears. Some segments of the news media clamored for information we could not divulge. And we all felt the stress of public pressure to apprehend Ted before he killed again.

Little could we know that Bundy had driven on in his Volkswagen to Utah and was murdering there (and in Colorado and Idaho), even before we had any good idea of how many women he might have murdered in our area.

Then there were problems we had no way of anticipating. Among these was the sheer volume of information (some potentially vital, the rest mostly useless, all of it difficult to evaluate) that quickly overwhelms a serial murder investigation. Officers and detectives are individuals with individual ways of pursuing leads. Until we had developed standardized tip sheets who, what, when, and where forms that could be compared, collated, and studied systematically the information we collected was really just a blizzard of jotted notes, most of them unintelligible except to the person who wrote them.

Another unwelcome surprise was how serial murders tend to invalidate certain basic assumptions of traditional homicide investigation. Specifically, there is usually a connection of some sort between victim and killer. They are often related or acquainted. Because of this, and because at first we could not assume that all, or even any, of Teds victims were complete strangers to him, we were obliged to go by the book, investigating each victims circle of contacts and who among them might have a reason for killing her. Although this work generated much information, it turned out to be only marginally useful.

Similarly and this problem was peculiar to Ted Bundy as a suspect we discovered the uselessness of showing his photo to possible witnesses. Even without the disguises and masks Ted used, he looked different in just about every photo taken of him. The two we had seemed to be of two different people, neither of whom resembled the Ted at the lake.

We learned lessons of a different type when it came to organizing ourselves into a multi-agency investigative task force. First of all, the formation of a task force represents a police consensus that there is indeed a serial killer on the loose. That can be an important psychological hurdle. Once everyone agrees on the nature of the problem, far less time will be wasted on extraneous investigation not germane to the task implicit in the term task force. A task-force approach promotes better organization of case materials, too. And it absolutely forces a detective to think of what is important to the overall, long-range mission, rather than what seems important that day.