Contents

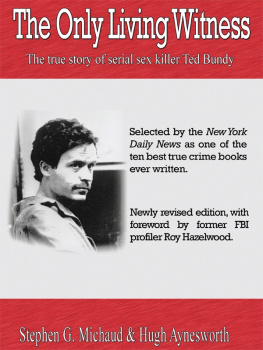

The Only Living Witness

The True Story of Serial Sex Killer Ted Bundy

by Stephen G. Michaud & Hugh Aynesworth

Published by Authorlink Press,

an imprint of Authorlink

www.authorlink.com

755 Laguna.

Irving, TX 75039-3218 USA

First published by Authorlink Press an imprint of Authorlink,

July 1999.

Copyright Stephen G. Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth, 1999

http://www.stephenmichaud.com

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without written permission of the publisher and copyright holder.

Published in the United States of America

2012 Authorlink Press

ISBN 978-1-928704-28-7 (ePub)

ISBN 978-1-928704-29-4 (print)

ISBN 978-1-928704-31-7 (Kindle)

ISBN 978-1-928704-35-5 (iPad)

Previously published by Authorlink Press, ISBN 1-928704-11-5

Previously published by Penguin Putnam, ISBN 0-451-16372-9

For Susan and Paula

Of all the infamous serial killers of the past two decades, Ted Bundy stands out as unique. Before he burst into the public consciousness, most people assumed that anyone capable of homicides heinous as the ones he committed had to be easily identifiable. As Bob Dekle, one of Bundys prosecutors, put it, People think a criminal is a hunchbacked, cross-eyed little monster, slithering through the dark, leaving a trail of slime. Theyre human beings.

Those of us who study aberrant criminal behavior understood that important fact. Except for certain extreme cases of psychotic behavior, sexual criminals tend to appear and behave just like everyone else. In my experience, the overwhelming majority of ritualistic offenders (of which Bundy was a prime example) are middle-class white males of European descent.

Well known examples include John Wayne Gacy, the Illinois serial killer of young men and boys; David (Son of Sam) Berkowitz; Albert DeSalvo, the Boston Strangler; and Harvey Glatman, the Lonely Hearts Killer, whose murders around southern California in the mid-1950s made Glatman the first high-profile serial killer. All of these men were intelligent, articulate, dedicated sexual murderers.

But you couldnt tell by looking at them. None betrayed himself in his daily life.

Bundys career was the most dramatic object lesson of all. He was the first coast-to-coast killer, the model of the traveling serial killer who took advantage of what Bundy called the anonymity factor. He was also the first celebrity killer, a consummate actor and a natural for television whose face and voice and courtroom demeanor were familiar all across the country.

One of Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworths most valuable contributions in The Only LivingWitness has been to demystify Bundy. Most of the book takes place behind the scenes in his life, as they explore the complex psychology of a deeply-troubled, emotionally-unstable young man whose wholesome facade never before had been pierced. That Stephen and Hugh did so with Bundys eager cooperation is testimony to their reporting skills.

But the greater achievement in The Only Living Witness is Bundys third-person ruminations on serial murder, speculations based on his personal experience. Not only did Bundy share with the authors a cogent and instructive reconstruction of the several developmental steps that lead to serial murder including the early manifestations of paraphilias such as voyeurism but he also confirmed much of what my colleagues at the Behavioral Science Unit were discovering in their own interview survey of incarcerated killers.

Although Bundy never actually confessed to Michaud and Aynesworth, he did reveal to them what is probably the most complete self-portrait ever painted by a serial killer. What he had to say is as relevant today as it was at the time, making The Only Living Witness as unique a document as Bundy was a killer. There are lessons in this book for everyone.

Roy Hazelwood, June 1999

I last saw Ted Bundy on a miserable day in early June. The Florida sun came up hot in the morning; there was a feel of bloat in the air, a rank sponginess that shortens the breath and makes the skin feel dirty, prickly.

Hugh and I drove southeast from the Quality Inn in Lake City along State Highway 100 toward the maximum security prison near the remote hamlet of Raiford. It is a thirty-five mile trip through the middle of north-central Florida, a flat, unrewarding stretch of scraggly pine trees and truck farms. This is not the Florida of Art Deco South Beach, Disney World and orange groves. This landscape is rural and mostly poor and has much more in common with the backwaters of southern Georgia than it does with the tourist country that begins farther down the Florida peninsula toward Orlando.

We passed a convenience store that served free coffee to highway patrolmen. A bit further along the straight, two-lane highway was the town of Lulu with its tiny post office and well-attended Baptist church. A good deal of praying and singing (and stomping and hollering) in the name of the Lord goes on in this part of Florida. On the car radio that morning there was a choice of farm reports, country music and gospel hours.

A massive semi zoomed by. Around Lulu, the country people are accustomed to the roar of the big rigs as they barrel up and down Highway 100. They are also accustomed to the splotches of fur, feathers, and spines squashed flat into the pavement under the truckers wheels. Buzzards and nimble crows work Highway 100 like so many Eighth Avenue hookers, with one eye on their business and the other on the lookout for The Man. As a car or truck approaches, the scavengers fly straight up and just high enough to clear the vehicles roof. Then they alight again on the roadway. Once in a while, the slower birds will misjudge a trucks height, or fail to notice another tall truck just behind it.

It was only eight-thirty, but already waves of heat shimmered up from the highway. We turned, and the road opened up onto a broad plain. To the right was the Union Correctional Institution, which is in Union County, and then the Florida State Prison itself, just a rifle shot away across the New River in Bradford County. Prison cattle stood motionless along the roadside, stupefied by the heat and the humidity. Their milk, which the prisoners consume, is often redolent of soil. Interspersed with the cows were inmate work gangs out with their uniformed guards, who cradled shotguns and wore sunglasses that coruscated in the bright morning light.

It was a banal vision of purgatory; the sullen, shuffling cons toiling under a heavy sun that glinted hard at them from their keepers shielded eyes. Stasis and timeless futility are common to all prisons; it only seemed more pronounced that day because of our mood. Hugh was hacking and wheezing from a respiratory infection. My brain was cottony from a hangover, and my stomach was sour from too much black coffee and aspirin.

When we arrived at the prison itself, both my hands were cramped and sore from clutching the steering wheel, as if Id been hanging from it.

For months, I had been coming to the prison to see Ted. Each time I drove up, I would be accosted by a blue-clad trusty, leaning on a rake in the parking lot, wanting to know if I was an attorney. This day, to my surprise, the importuning felons were missing. And gone, too, were the raucous seagulls that in the springtime wheel and screech above the prison kitchens, or stand nattering at one another under the guard towers. Many inmates will swear that they are served creamed chicken with suspicious frequency during seagull season.